How to Write a Screenplay: A 10-Step Guide

Without a doubt, the biggest question for those taking the first steps in becoming a professional screenwriter is how to write a screenplay.

Writing a script can be an arduous process for beginning screenwriters. However, when you learn the basic steps that need to be taken during the development, writing, and rewriting of a screenplay, things can get quite a bit easier for you.

While there is no single surefire way to go about writing a script, having a structured process to work from helps to simplify the undertaking, allowing you to focus on conjuring the best concepts, characters, and stories for your screenplays.

With that in mind, here we present a simple, straightforward, easy-to-follow yet detailed guide on how to write a screenplay in ten structured steps. Be sure to explore the accompanying links found within each step for more elaboration, information, tools, and professional knowledge that will help you get through this process.

Table of Contents

- Screenwriting Terms You Need to Know

- Step #1: Get Screenwriting Software

- Step #2: Come Up With A Great Story Idea

- Step #3: Write a Logline

- Step #4: Develop Your Characters

- Midway Break: Script Title, Research, and Story Visualization

- Step #5: Write a Treatment

- Step #6: Create an Outline

- Step #7: Write the First Draft

- Step #8: Take a Writing Break

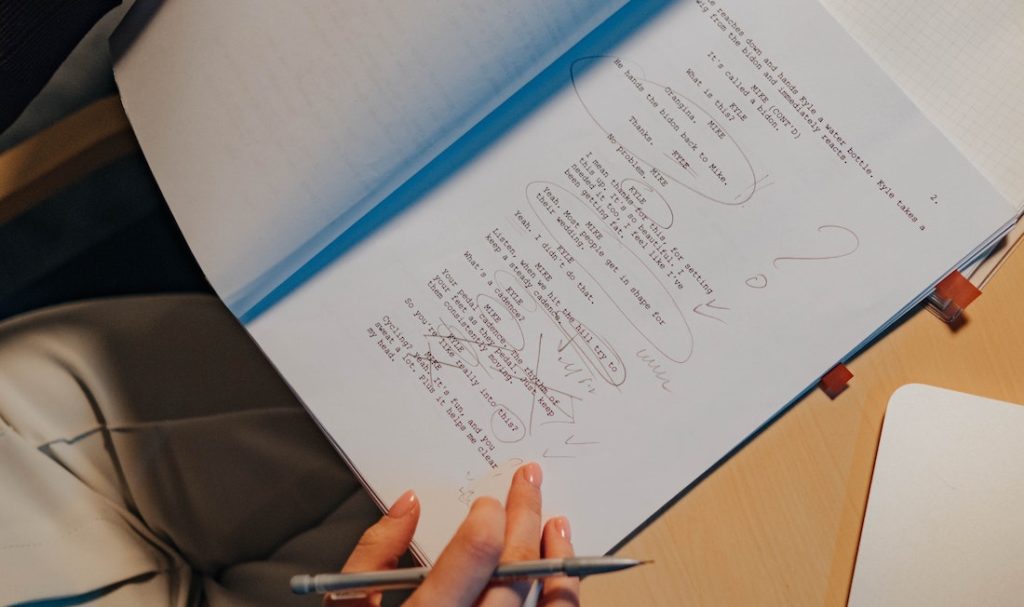

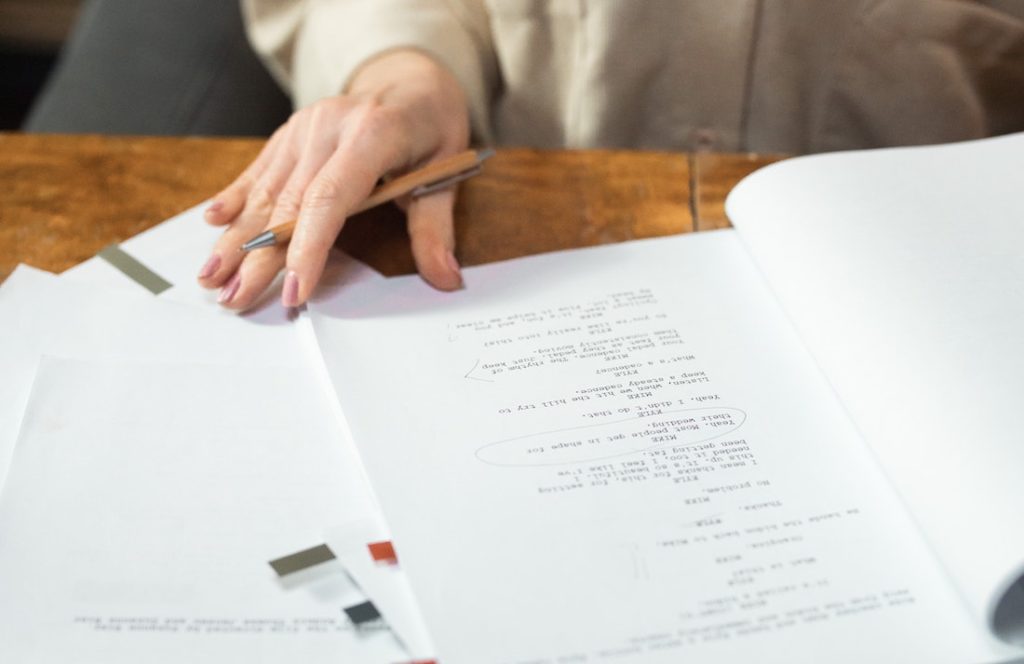

- Step #9: Rewrite

- Step #10: Complete Your Final Draft

Screenwriting Terms You Need to Know

Before we dive into the first step, let's go over an important term you'll need to know: spec script.

What is a Spec Script?

A spec script is a screenplay written under speculation that it will be acquired by a studio, network, or production company for the purpose of production and distribution. In short, you haven't been paid to write it. You're writing the screenplay on your own accord with the hopes of selling it to the film and television industry for production.

What Are the Pros of Writing a Spec Script?

The benefits of writing on spec include the following:

- No one looking over your shoulder.

- You write what you want when you want.

- You write the screenplay how you envision it, while hopefully following general industry guidelines and expectations to increase your chances of selling it.

As a beginning or unestablished screenwriter, writing on spec allows you to hone your skills and work on your craft through the development, writing, and rewriting process, unhindered by contracted deadlines and pressure from executives.

What Are the Cons of Writing a Spec Script?

But there's a catch to this freedom — you're not getting paid yet. You are working under the speculation that what you write will be received well enough for the powers that be to invest their valuable time and money in packaging, selling, producing, and distributing your cinematic story.

The Difference Between Writing on Spec and Writing On Assignment

Writing "on spec" and writing "on assignment" are different. Let's go over a few ways in which they differ.

Writing on Spec

Spec scripts are actually the least lucrative way to earn a living as a screenwriter. A majority of the screenwriting contracts in the film and television industry are paid writing assignments, where a screenwriter is hired to write from a pitched concept, a rewrite of a script they own, source material, or existing intellectual property owned by the hiring company.

When a screenwriter is being considered for a screenwriting assignment, their spec scripts are actually utilized as writing samples to help studios, production companies, and networks determine if the writer is a good fit for the assignment.

Writing on Assignment

When you write on assignment, the process is a little more structured by contract variants and mandates.

- You likely need to write development materials like synopses, treatments, and outlines as part of the collaboration process with the powers that be.

- You have development executives, producers, and directors reviewing your drafts and giving you notes that you will need to apply.

- You have strict deadlines that need to be met.

But with writing assignments, you're getting paid to write — which should be the goal for anyone wanting to become a professional screenwriter.

Spec scripts can be passion projects for screenwriters. Writing assignments pay the bills.

So while you're writing on spec, no, you're not bound by tight deadlines and time constraints. However, it will help you to train yourself to write like a professional under general industry deadlines and guidelines so you can be ready for success when it comes.

Read ScreenCraft's 5 Things to Expect During Paid Screenwriting Assignments!

This 10-step guide will help you build the structured process you need to get you ready for that success. As we mentioned before, there's no single way to write a screenplay. Every screenwriter will have their own wants, needs, strengths, weaknesses, and preferences when it comes to how and why they write their scripts. Use these proven steps as the foundation for your writing process, and we promise that you'll be a few steps closer to your goal of selling your screenplay — or being paid to write on assignment — and seeing your words come to life on the screen.

Step #1: Get Screenwriting Software

Screenwriting software is essential for screenwriters. The software is a necessary tool that aids the screenwriter in writing under inescapable format constraints and helps to later ease the collaboration process between screenwriters, directors, producers, development executives, actors, and film crews. Because of the importance of that collaboration — and the ease of which is offered to you — it is highly recommended that the first step of your writing process is acquiring and utilizing screenwriting software.

What Screenwriting Software is Best?

Many options are presented when it comes to which screenwriting software package you choose, each with different variances of cost, tools, and features.

There are free or lower-cost options that offer you the basic format tools, and there are more costly options that represent the industry standard and have more additional development and collaborative features.

- Final Draft is the industry standard. It's much more costly than free options, but you can get it as low as $199. It will be the best money spent for your screenwriting process.

- Celtx is the most popular lower-cost option, but screenwriters should know that when you do get to the level where you're writing under paid assignment contracts, most studios, production companies, and networks prefer Final Draft files when it comes to reports, file types, and collaborative features that they request.

Read ScreenCraft's The Ultimate Guide to Screenwriting Software to learn more!

Do You Need Screenwriting Software?

Short answer, no. You can absolutely use any old word processor to write a script, but that means you'll be responsible for maintaining any and all formatting standards. Every margin, every indent, every italicized text — it's up to you to make sure it's all correct. And there are plenty of script formatting mistakes that new writers make consistently even with software!

This is primarily what makes screenwriting software so attractive and necessary for so many writers — it takes care of all the formatting so you can focus on the best part of the process — storytelling.

"Is the script format really that important?"

Yes. And there are specific reasons why.

Screenplay Format 101

Screenplays are not like short stories, novellas, or novels. They have a specific format that screenwriters need to adhere to because film and television are collaborative mediums.

Furthermore, scripts are both auditory and visual blueprints for eventual cinematic features and episodic television episodes, so the format exists to create an easy-to-visualize and easy-to-adapt cinematic story filled with locations, dialogue, and actions that directors, actors, and film crews can bring to life from script to screen.

Learn the History and Evolution of the Modern Screenplay Format!

Master Scene Format

The master scene format is the essential script format that you should follow. It represents the best way to interpret visuals and dialogue from your creative mind to the page for others to decipher as easily as possible.

Screenplay Format Elements

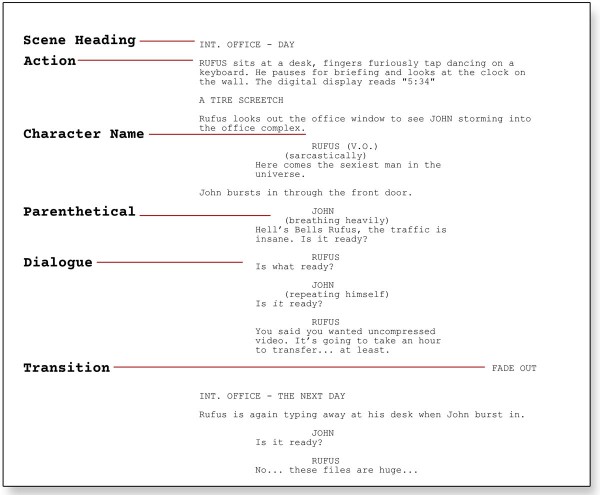

The screenplay format elements of Scene Heading, Action, Character Name, Parenthetical (used few and far between), Dialogue, and Transition (used sparingly) are all that you need to tell a cinematic story meant for the big or small screen.

Here's a quick breakdown of each of these elements, as well as a visual guide on what they look like on the page:

- Scene Heading: Also known as the "slug line," these headings communicate the setting of a scene, including whether it takes place inside or outside, the location, and the time of day.

- Action: This describes the action that can be seen or heard.

- Character Name: This indicates the character that is delivering the dialogue.

- Parenthetical: This provides context or instruction for the dialogue delivery. (Use these sparingly and only when necessary.)

- Dialogue: This represents the words delivered by actors.

- Transition: This marks the change from one scene to another. (Use these sparingly and only when necessary.)

There are subtle variances in the format — musicals, for example, are formatted a little differently — but the master scene elements are the most universal formatting guidelines to follow for all cinematic platforms.

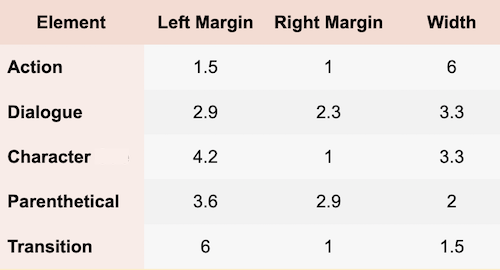

Screenplay Margins

Each margin settings for these master scene elements include:

If there are any format "rules" that cannot be bent, they are represented by these margin settings, which help formulate the basic and universal script page size and aesthetic.

When you purchase and utilize screenwriting software, you avoid having to worry about any margin settings. You can deliver what is needed in that format front by the push of a button or two as you write.

Because the screenplay format is much more technical compared to writing short stories, novellas, and novels, some beginning screenwriters look upon the format with anxiety. It doesn't have to be that way. If you follow the basic screenplay elements and utilize screenwriting software to ensure that you're adhering to the strict margin settings for each, you can focus more on telling great stories with strong and compelling characters.

For a more detailed breakdown of how to format a script, read ScreenCraft's How to Format a Script!

Step #2: Come Up With A Great Story Idea

Okay, you've got your screenwriting software and you're ready to start writing, only... you don't have a story idea.

Or maybe you do but you're not sure if it's up to snuff. It's very easy to just roll with the first idea that comes to mind. But that's often the first mistake that most beginning and unestablished screenwriters make.

Either way, let's go over some concepts and tools that'll make it easier for you to come up with a great story idea.

Find a Great Concept

As the great Crusades Knight in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade once said:

"You must choose. But choose wisely."

The most common phrase that you'll hear in Hollywood development offices is concept is everything. Yes, everyone also wants great characters, compelling drama, high stakes, twists and turns, and engaging stories. But in the end, it's the concept that sells the project.

What is a Story Concept?

- It's the logline (see below) that gets you in the door.

- It's the central concept that sells the project to distributors.

- It's the great idea that is sold to the audience.

It's the great story idea.

That great idea does need to be delivered in amazing fashion by a great script packed with engaging and empathetic characters. You need to deliver on the promise of your great story idea by writing an outstanding screenplay that explores the character and story dynamics of that concept. But, make no mistake, you need to choose the concepts of your script very wisely.

Do You Need to Have a Great Concept?

Screenwriters need to understand that, sure, there is a market for smaller character pieces and quirky character-driven comedies and dramedies. However, those are more popular in the independent film market through auteur films and indie flicks that are discovered through the film festival circuit.

When you're writing on spec in hopes of selling your script to Hollywood, you need to do your best to find concepts that stand out from the rest. The spec market is highly competitive. Regular run-of-the-mill dramas and quirky character pieces don't represent lucrative investments for studios, production companies, and distributors. They need and want concepts that draw audiences to the theater — or get them to click while they're searching their streaming platforms for something to watch.

What are some ways to find those great ideas?

How to Come Up With a Great Concept

While there's no single secret to finding a great concept that will get studios and producers to bite, there are many creative ways you can explore potential ideas and see if they are compelling enough to encompass a whole screenplay.

Story Prompts

Sometimes reading and writing simple story prompts is the easiest way to get those creative juices flowing.

You can explore "What If..." scenarios, "This Meets That" story hybrids, or story prompts based on true stories that would make for compelling screenplays.

Read ScreenCraft's 101 Story Prompts Series to get your creative juices flowing!

Watch Movies

And believe it or not, you can also turn to what may be your favorite pastime as a cinematic storyteller and movie lover — watching movies — to get your creative mind flowing. It's pretty common to be watching some of your favorite flicks — or new ones that engage you — and find your mind wandering to elements within those movies that weren't fully explored. Or maybe your imagination begins to wonder how a certain story or character could have been handled differently.

For example:

- What if the story of THE SIXTH SENSE focused not on the people that could see ghosts, but rather on the ghosts themselves as they try to reach out to people to solve the mystery of their death?

- What if GOOD WILL HUNTING was a thriller where the government forced a character like Will to use his talents to break secret codes?

- What if the aliens in any alien abduction movie are actually humans from the future trying to find a cure for a pandemic that's killing off the human race?

Choose Your Genre Wisely

But sometimes it's not enough to just have a great idea. Writing that idea within a specific genre is also a big decision-maker for the impact your idea has on Hollywood when you start marketing your eventual script to studios, production companies, and distributors.

"Well, won't the movie concept dictate what the genre is?"

Not always.

Case Study: Armageddon vs. Deep Impact vs. Don't Look Up

In ScreenCraft's How to Choose the Right Movie Genre for Your Concept, we put this notion to the test by offering a general concept.

An asteroid is going to impact the earth, and a team is being sent into space to stop it before kills humanity as we know it.

That's a great idea for a movie. It's almost a great logline as well. But it doesn't necessarily dictate the genre and subgenre. In 1998, two movies debuted with that very same premise — Armageddon and Deep Impact. But both were very different films written under very different genres and subgenres.

- Armageddon was an action comedy mixed in with science fiction adventure.

- Deep Impact was a drama mixed in with science fiction.

They handled the same premise in many different ways.

- Armageddon focused on big laughs, sweeping romance, high-octane action, and special effects-driven space adventure. Yes, it certainly had dramatic moments, but the action, thrills, and special effects sequences overshadowed them.

- Deep Impact focused on the drama of losing loved ones amidst the genuine and scary thought that our world could end due to circumstances out of our control. Yes, it had trailer moments of major tsunami floods killing millions, but the focus was on the drama.

A more contemporary take on the idea of people struggling to survive during an impending and eventual asteroid impact would be Best Picture nominee Don't Look Up, an apocalyptic political satire black comedy.

Play with Genre

Placing your great story idea into different genres — and the various story, character, and setting elements usually found in those different genres — is a masterful way to find something both familiar and unique, two elements that Hollywood insiders (and audiences) love when choosing which screenplays to move forward on.

What is the takeaway when it comes to finding great story ideas?

- Choose wisely.

- Be creative when you're exploring options.

- Have fun with it.

- Make lists of potential ideas to choose from.

- And inject those ideas into different genre possibilities.

Read ScreenCraft's What Screenwriters Are Up Against in Every Genre!

Step #3: Write a Logline

If concept is everything in Hollywood, the logline is the thing that sells the concept in the shortest time possible. Think of them as the short and sweet literary forms of coming attractions. So, you could say that loglines are really, really, really important.

What is a Logline?

A logline is the simple 25-50 word (give or take) preview that captures the core dynamics of your concept. It's what sells your concept. It's an ultra-powerful sentence that can hook a reader and force them to read your script.

What Are the Elements of a Great Logline?

The purpose of a logline is to inform the studio, production company, and distributor:

- The main character(s)

- The world they live in

- The inciting incident

- The major conflict they must face

- The stakes at hand

A great logline should include these elements.

How to Write a Great Logline

You're not telling a story in a logline. You're presenting the core concept of your script. You don't need to delve into twists, character arcs, and plot. You're simply conveying the core idea — the initial seed from that which the plot, characters, twists, turns, and ensuing conflict grows.

The basic formula that you can start with — once you've chosen the idea you want to develop — will help give you the foundation of what needs to be in a logline.

- When [INCITING INCIDENT OCCURS]...

- A [CHARACTER TYPE]...

- Must [OBJECTIVE]...

- Before [STAKES].

When a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach community, a local sheriff, a marine biologist, and an old seafarer must hunt the beast down before it kills again.

Starting with this basic formula allows you to identify the inciting incident/major conflict, the protagonist(s), the goal they have within the story, and the main stakes. After that, you can tweak the verbiage and structure to find the best representation of your idea that leaves the reader engaged and compelled to learn more.

For a more detailed breakdown of how to write loglines, Read ScreenCraft's The Simple Guide to Writing a Logline!

'The Godfather'

Examples of Great Loglines

Still not sure what constitutes a great logline? Well, here are a few from some popular movies that'll give you an idea of what to shoot for:

The aging patriarch of an organized crime dynasty transfers control of his clandestine empire to his reluctant son. (THE GODFATHER)

After a simple jewelry heist goes terribly wrong, the surviving criminals begin to suspect that one of them is a police informant. (RESERVOIR DOGS)

With the help of a German bounty hunter, a freed slave sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner. (DJANGO UNCHAINED)

A Las Vegas-set comedy centered around three groomsmen who lose their about-to-be-wed buddy during their drunken misadventures and then must retrace their steps in order to find him. (THE HANGOVER)

A young F.B.I. cadet must confide in an incarcerated and manipulative killer to receive his help on catching another serial killer who skins his victims. (SILENCE OF THE LAMBS)

A thief who steals corporate secrets through the use of dream-sharing technology is given the inverse task of planting an idea into the mind of a CEO. (INCEPTION)

A fast-track lawyer can’t lie for 24 hours due to his son’s birthday wish after the lawyer turns his son down for the last time. (LIAR LIAR)

'Jaws'

When a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach community, it's up to a local sheriff, a marine biologist, and an old seafarer to hunt the beast down. (JAWS)

Seventy-eight-year-old Carl Fredricksen travels to Paradise Falls in his home equipped with balloons, inadvertently taking a young stowaway. (UP)

A cowboy doll is profoundly threatened and jealous when a new spaceman figure supplants him as top toy in a boy's room. (TOY STORY)

A young janitor at M.I.T. has a gift for mathematics but needs help from a psychologist to find direction in his life. (GOOD WILL HUNTING)

Two astronauts work together to survive after an accident leaves them stranded in space. (GRAVITY)

In a post-apocalyptic world, a family is forced to live in silence while hiding from monsters with ultra-sensitive hearing. (A QUIET PLACE)

A troubled child summons the courage to help a friendly alien escape Earth and return to his home world. (E.T.)

Read Screencraft's 101 Best Movie Loglines Screenwriters Can Learn From and 22 Loglines From This Year's Sundance Films (And Why They Got Festival Attention)!

When Should a Logline Be Written?

Some screenwriters make the mistake of waiting until after they've written their script to craft a compelling logline. While you can certainly rewrite the logline during the marketing phase of trying to sell your script, the logline is a great tool for the writing process as well. Most professional screenwriters are tasked with writing them before the scriptwriting process even begins.

When you write a great logline before you start writing, you can use it as a compass to ensure that you're writing around what the logline provides — the central core concept of your story.

Step #4: Develop Your Characters

You've got the great idea. You know what genre it falls under. You've articulated that great idea into a compelling and engaging logline that communicates that genre and encapsulates the core concept of the script. Now it's time to start delving into the characters that will populate the world you've been slowly creating through this development process.

5 Key Character Types

There are generally five types of characters in screenplays:

- Protagonists

- Antagonists

- Villains

- Supporting Characters

- Stock Characters

Protagonists

Protagonists are the lead characters in your screenplays. Think Indiana Jones, Katniss Everdeen, Harry Potter, James Bond.

Some scripts will have a sole protagonist, while others will have multiple. These are the characters that have a central role in the progression of the story, and plot.

- They are the ones reacting to the conflict presented by the concept.

- They are the ones central to the story and plot.

- They are the ones that have a full character arc as a result of their actions and reactions to the conflicts of the story.

'Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark'

Antagonists and Villains

Some believe that the terms antagonist and villain are interchangeable when they are actually quite different.

- Villains are defined as “evil” characters intent on harming others.

- Antagonists are defined as characters that work in opposition to the protagonist (the hero).

What's the Difference Between a Villain and an Antagonist?

Villains aren’t always the antagonists — often, but not always — and antagonists aren’t always the villains. Case in point, Sadness from Inside Out. While she is clearly the antagonist by definition — she is in opposition to Joy's goal of keeping Riley happy — she is not the villain because there are no evil intentions.

There is some gray area to be sure. Villains and Antagonists (and even Protagonists to a degree) do not live in a black-and-white world in the realm of cinematic and literary storytelling — a lesson that most writers can learn from. The best stories often blur the lines between antagonist, villain, and protagonist. That's where great character development comes into play.

In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Principal Rooney is clearly not evil. However, if you look at it from the context of the film — namely from the perspective of teenagers like Ferris, Sloane, and Cameron — Rooney is “evil” in terms of representing authority that opposes their will to have fun and enjoy life and school to their fullest.

In the case of Sadness in Inside Out, Joy eventually realizes that Sadness is not only an integral part of Riley's humanity but she's also a key element in ensuring that she's able to cope with loss in order to feel joy once again.

So the word “evil” must be looked upon in a particular context, namely through the eyes of the protagonist. In fact, one of the greatest villains in cinematic history is Man. Man is the personification of evil in Disney’s Bambi. Now, we all know Man (in general, at least) isn’t evil. However, in the eyes of Bambi, Man killed the one Bambi loves for no good reason. So it’s all in the context.

There is some gray area to be sure. Villains and Antagonists (and even Protagonists to a degree) do not live in a black-and-white world in the realm of cinematic and literary storytelling — a lesson that most writers can learn from. The best stories often blur the lines between antagonist, villain, and protagonist. That's where great character development comes into play.

Supporting Characters

Supporting (or secondary) characters may not always directly impact the central conflict, story, and plot, but they serve multiple purposes in screenplays.

- Comic relief

- Tying different main characters together

- Connecting plot points

- Supporting the main characters

- Antagonizing the main characters

- Informing the main characters

- Testing the protagonists' values, ethics, and morals

It's good to be aware of who your supporting characters are and what purpose they serve within the context of the story. And the supporting characters you surround your protagonist with open up many more doors for additional character depth and arc.

Read ScreenCraft's Three Types of Supporting Characters Your Protagonist Needs!

Stock Characters

Stock Characters are archetypal characters found throughout most cinematic stories. These are the recurring types of characters that audiences recognize from movies and episodic series.

- Authority figures (teachers, principals, police officers, government agents, etc.)

- Neighbors

- Children

- Family Members

- Friends

While stock characters can be building blocks used to create supporting characters, protagonists, antagonists, and villains, they are often used as plot tools for single scenes or smaller scope C stories within your scripts.

Read ScreenCraft's Archetypes and Stock Characters Screenwriters Can Mold!

Methods for Developing Your Characters

Character depth can come in many different forms.

You can showcase character depth visually through their actions and reactions.

You can showcase character depth visually through their actions and reactions.- You can develop backstories that explain those actions and reactions.

- You can assign traits, quirks, and physical descriptions that define their characterizations.

There's no single rule, process, or guideline to follow. The best thing that you can do is find what works right for you and make sure that everything you assign to the character is present within the script and relates to the story and plot presented within the script.

Do You Need to Develop ALL Characters?

Remember that you don't need to do this for every single character within your script. There's not enough time in your movie to offer up much character development for stock characters. Supporting characters can be given a bit more depth, but even with them, anything too in-depth is too much and takes away from where character depth is really needed.

Protagonist character depth is where your focus should be because they need to have various internal and external arcs present throughout the story from beginning to end.

Read ScreenCraft's Acceptance, Revelation, and Contentment: Exploring Your Character's Inner ARC and Action, Reaction, Consequences: Exploring Your Hero's External ARC!

- Find Creative Ways to Conjure Perfect Character Names!

- Answer Character Questions and The Ultimate List of Story Development Questions to develop your characters further.

These simple steps can help you develop great characters to go along with your great movie idea.

Midway Break: Script Title, Research, and Story Visualization

Before we get into Step #5 and beyond, you need to take some time to do the front-end work that's necessary for all screenplays.

- Research

- Find Your Script Title

- Story Visualization

It's very tempting to jump into the screenwriting process after doing this initial concept and character development, but there's some critical work to be done before you deliver into steps 5-10.

Research

Research is a critical factor in developing a compelling cinematic story, whether it's studying the world your fictional character will inhabit or learning everything you can about the real-life elements of your script.

Read ScreenCraft's 7 Things to Remember While Researching Your Screenplay!

And research goes beyond the story, world, and facts.

When you have a concept for a screenplay, one thing you should do is research that concept to make sure that there's nothing else out there like it.

We live in a collective world where we are all inspired, intrigued, and informed by the same things. There's bound to be a lot of cross-over. For screenwriters, there's nothing worse than getting through an entire script and discovering that Hollywood has already greenlit or produced one, if not multiple, films or TV series with the same concept you just finished spending months writing. It's heart-wrenching.

Once you have that idea in your head, jump on Google and start seeing if any other projects like it have been made or are in the works. And if something is similar, perhaps you can find a way to make yours different — if not better.

Script Title

Now it's time to give your project some identity. A new screenplay is like your baby. You need to nurture it, feed it, and let it grow. And that process starts by naming it.

Some will say that the screenplay title doesn't matter because it's likely going to be changed down the line anyway. There is some truth to that. If your script gets into industry hands, the title could (and probably will) go through any number of variations based on marketing and creative input from many individuals.

However, the title is a weapon in your literary and cinematic arsenal that you use to draw attention to your work. A great title can raise the eyebrow of that industry executive.

Above and beyond that, it's exciting to find that fantastic title.

- It offers instant energy and excitement as you go into the writing process.

- It gives instant identity to what you are trying to do with your cinematic story.

- It fuels your investment in the project.

Take the time to find that perfect title for your script before you delve into the meat of the story and plot. You'll often find that a great title can lead you toward the story and plot decisions you make in steps 5-10.

For great tips on how to find the perfect title, Read ScreenCraft's How to Write Screenplay Titles That Don't Suck!

Story Visualization

Visualization is a crucial part of the process. How can you possibly communicate and describe a visual through prose without first seeing it in your creative mind's eye first?

Writing isn't always typing. Visualization is just as much of your writing process as typing is — if not more.

- Visualize the movie.

- Daydream.

- Watch movies and TV shows that are similar in tone, genre, and atmosphere.

- Feed your brain.

- Grow that seed of a concept.

You can visualize your movie as you stare out the window, feed the baby, prepare lunch for your middle schoolers, or wait for that work report to print.

That long work commute can be your magic time to dream up your story, characters, and narrative. When you work out, go for a walk or run, or go for a bike ride, you can be writing in your head, creating worlds and characters that inhabit those worlds.

- Visualizing is writing.

- Try to see upwards of 75% of your script in your head before you type anything.

- At the very least, see the broad strokes of your movie in movie trailer form.

You'll find that this front-end work will be invaluable when it comes to the necessary preparation for the screenwriting process of writing your script.

Step #5: Write a Treatment

Now that you've finished your logline, it's time to write a treatment.

What is a Treatment for a Screenplay?

A treatment for your script is a document that summarizes the big-picture elements of your story. The eventual screenplay will have the stylistic delivery of the story pitched within the treatment.

What's the Difference Between a Synopsis and a Treatment?

Where a synopsis would generally cover the broad strokes of the story within a few paragraphs, treatments cover the specifics of the story, utilizing prose in the form of descriptive paragraphs that tell the story from beginning to end with all of the character descriptions, plot points, twists, turns, and revelations.

How Long Should a Treatment Be?

The length of treatments varies, with most coming in at 7-10 pages. You generally want to keep the treatment as short as possible while still offering the necessary length to tell the whole story from beginning to end. In short, you're not writing a book — you're writing a summary.

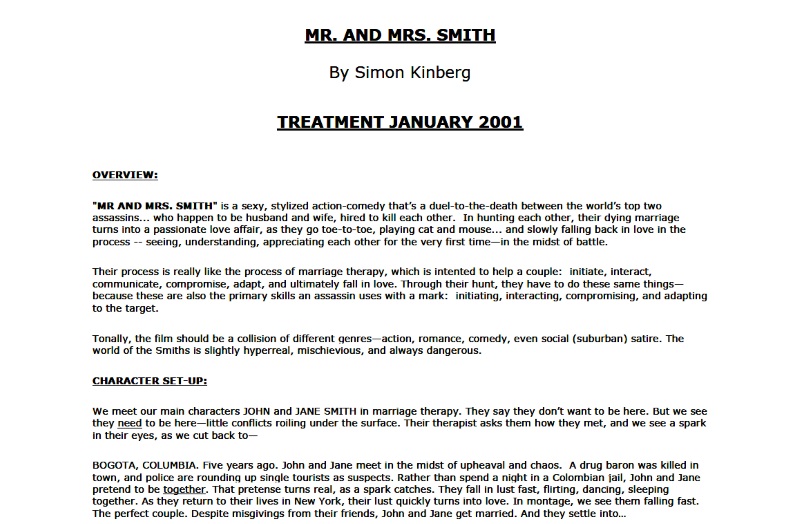

Hollywood screenwriter Simon Kindberg shared the treatment for his eventual action hit Mr. and Mrs. Smith over at Creative Screenwriting Magazine.

His treatment clocks in at just four pages. It offers an overview, which touches on the genre, the characters, their relationship, and the story. Check out the full treatment for Mr. and Mrs. Smith!

Benefits of Writing a Treatment

While writing treatments isn't a necessary step for all screenwriters and screenplays, they can be an effective tool.

Treatments Help You Find Your Story Window

It offers you the chance to find your story window, which, in turn, helps to compact your story into a plot and structure that can fit the confines of a feature-length movie. It's also a document where you can work out your plot points and see how the story flows and progresses.

Treatments Help You Visualize Your Story

Once again, it's tempting to jump into the screenplay without doing the front-end work. While we mentioned researching your script, finding your script title, and visualizing your story as key front-end tasks, writing a treatment can be a very effective next step that takes that visualization and puts it into context with literary elaboration and necessary story and plot organization. This allows you to build the foundation of structure you'll need to tell the story.

Knowing How to Write Treatments Is Important for Going Pro

The ability to write treatments comes in handy when you start writing on assignment. Most professional screenwriters are required to write treatments during their development process, so it's a vital professional skill to learn — and one that can help you in your screenwriting development as you hone your craft.

Read ScreenCraft's 21 Movie Treatments and Outlines That Every Screenwriter Should Read!

Step #6: Create an Outline

If treatments are there to help you collect all of the character arcs, story arcs, plot points, twists, turns, and reveals you need to write an amazing script, outlines are there to help you prepare a visual breakdown of how you'll utilize those elements within organized scenes.

If treatments are there to help you collect all of the character arcs, story arcs, plot points, twists, turns, and reveals you need to write an amazing script, outlines are there to help you prepare a visual breakdown of how you'll utilize those elements within organized scenes.

Once again, it's very tempting to jump into the script without doing front-end work like this, but any professional will tell you about the value of outlines.

Read ScreenCraft's To Outline, Or Not to Outline, That Is the Screenwriting Question!

What Does a Screenplay Outline Contain?

An outline is basically a numerated or bullet point beat sheet that communicates what's being seen and said using anywhere from a couple of sentences to a short paragraph for each story beat.

Read More: What is a Story Beat?

- Usually 7-8 pages long

- Anywhere from 35-45 beats

You can take your treatment and organize all of those character, story, and plot elements into a beat sheet for the screenplay. The outline covers every single story and character beat. You may not have every single scene in the outline (leaving you room for story and character evolution and discovery), but it's the closest thing to a scene-to-scene breakdown.

What Are the Benefits of Creating an Outline for Your Screenplay?

Some screenwriters love them and others hate them. Regardless of where you stand, there are some very clear benefits to creating an outline for your screenplay.

You Can Make Big Choices Before Doing a Ton of Writing

You can use outlines to make creative and editorial choices before the time is taken to write those scenes and moments in their cinematic entirety via the screenplay format. That can save you a lot of time and effort when it comes time to rewrite.

Read ScreenCraft's Why Screenwriters Should Think Like Editors!

You Can Write a Stronger First Draft

Screenplays, once written, can be a house of cards where if you take one card out, all others will come crumbling down.

It's very difficult to change plot points and story structure within a completed screenplay. But when you organize these elements before that process in outlines, it's so much easier to move the pieces of your story and plot puzzle around, creating the necessary and desired structure to tell your cinematic story.

You Can Maintain Your Sanity

For some, trying to flesh out an entire story without an outline can be a confusing and frustrating endeavor. And screenwriting, for the most part, is supposed to be fun and fulfilling — it's hard to feel that way when you're constantly getting lost in your own storytelling.

Key Elements to Address in an Outline

Plot

Many assume that plot and story are interchangeable terms. They're not. And it's good to know the difference between plot and story as you begin to outline your screenplay.

The story covers the who, what, and where of your screenplay.

- Who are the characters?

- What conflicts are they facing?

- Where is this all taking place?

The plot covers the how, when, and why of your story.

- How are the who of your story affected?

- When does the what of your story happen?

- Why does it happen where your story takes place, and why does it affect the who of your story?

For an even more thorough breakdown, read ScreenCraft's What Is a Plot?

You utilize your treatments and outlines to fine-tune the plot points and find a cinematic presentational structure that works for your script.

Story Structure

Story structure encompasses the basic choices you can make to determine how you want to tell your cinematic story. The general structure of any story is embedded in our DNA:

- Beginning

- Middle

- End

You introduce your characters in their ordinary world (beginning), present a conflict that they are forced to deal with while showcasing their true and evolving character through their actions and reactions to it (middle), and then they either succumb to the conflicts thrust upon them or triumph over them.

That's story structure at its core. You won't find a story in any medium that doesn't follow the three-act structure of Beginning, Middle, and End.

You can also find different ways to tell your story through many different types of story structures that play with the chronological order presented in your outline.

Read ScreenCraft's 10 Screenplay Structures That Screenwriters Can Use!

There are a lot of options when it comes to how you structure your story. Whichever story structure you choose (the three-act structure is the most utilized story structure), you utilize the outline (and the treatment before it) to help shape the cinematic story you'll tell when you start writing the script.

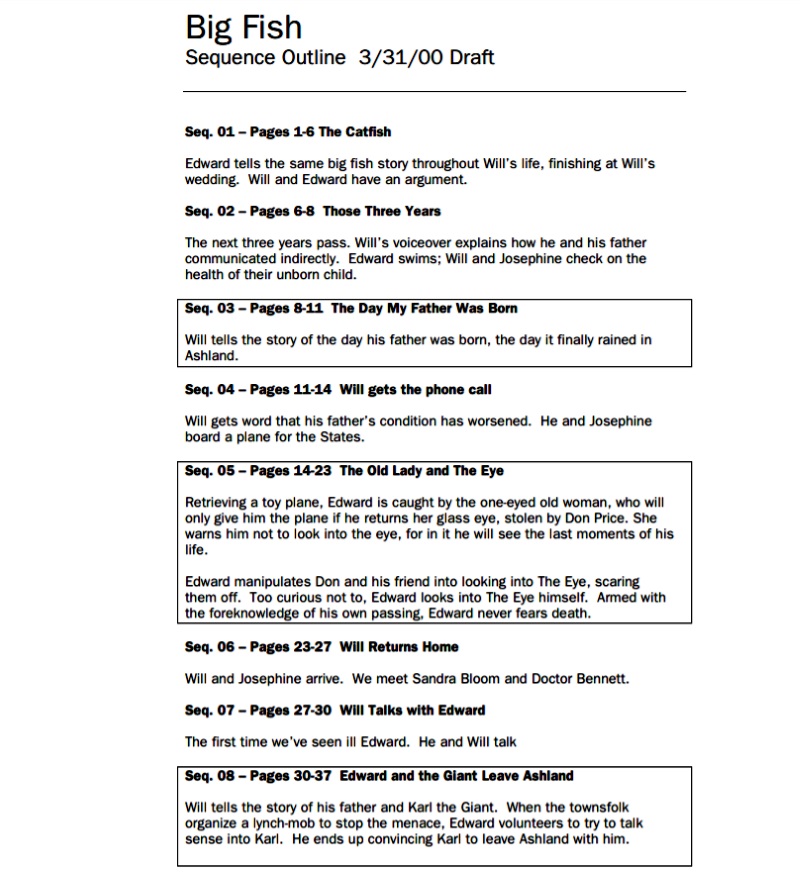

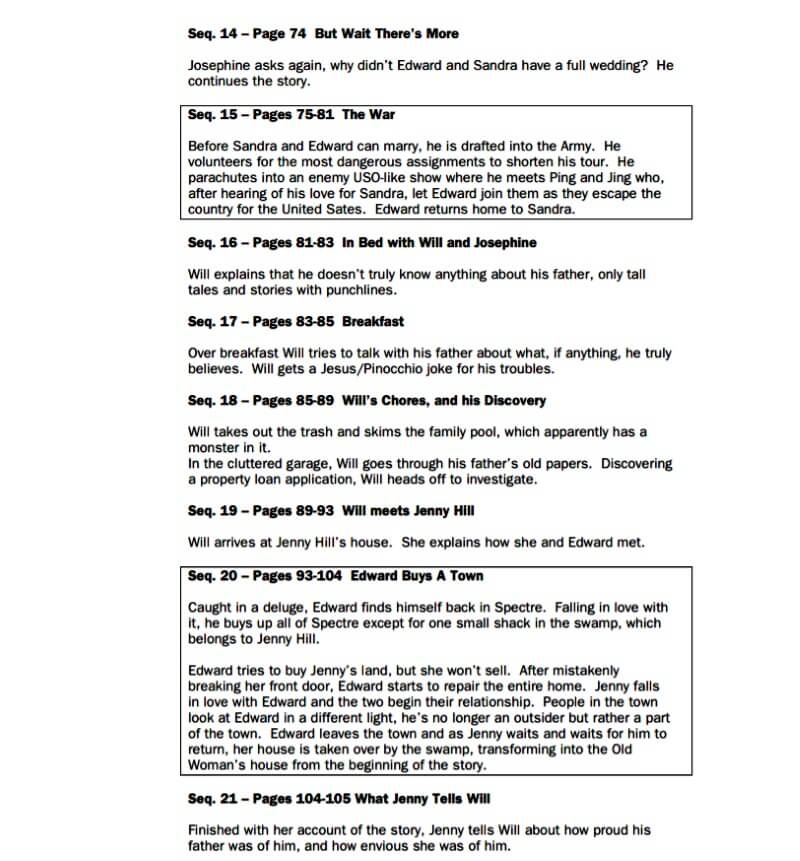

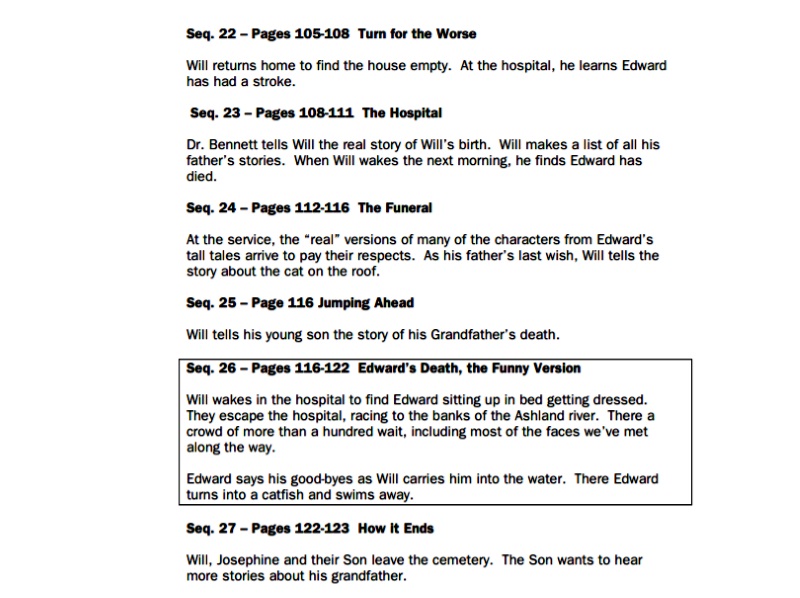

Case Study: The Outline for Big Fish

Here is an example that Hollywood screenwriter John August shared on his podcast site. The script he was developing was Tim Burton's Big Fish.

He likely used this for his collaboration with Burton and the producer. You could use this type of format — minus the page numbers — as an outline that offers slightly more detail if needed.

As you can see, outlines are all about organizing the core of each and every scene and moment within a screenplay.

Step #7: Write the First Draft

Are you ready? Let's review:

- You know what a spec script is.

- You've got the screenwriting software.

- You know the format.

- You've come up with a great idea.

- You've written a logline that acts as your story compass.

- You've developed your characters.

- You've got a working script title (you've named your baby).

- You've done the necessary research.

- You've taken the time to visualize your story.

- You've possibly written a treatment.

- You've hopefully at least written an outline to find the structure and organize the scenes you'll be writing.

Now it's time to sit down and get those fingers moving. It's time to make your story come to life on the page.

There are many ways to dive into the first draft. We've covered different approaches in past posts.

Read ScreenCraft's 5 Easy Ways to Conquer Your First Draft!

Here, we're going to keep it simple. And we're also going to provide an opportunity for you to learn how to write like a professional.

Have a Page Limit Goal

You may have read about the old adage that one page equals one minute of screen time. It's actually just a barometer — not an exact science — but one that can be very telling.

Screenplays are blueprints for movies. While there is certainly a literary dynamic to them, scripts are there to tell a visual story within the confines of 90-120 minutes of screen time. Thus, using the age-old barometer of one page equalling one minute of screen time dictates that the desired page amount for a spec script should be 90-120 pages. That's 90 at the very least, and 120 at the very, very most.

However, a more realistic page count is that sweet spot of 100-115 pages.

Having a page count goal going into the writing process is so invaluable to your writing process. You'll likely fall short or go over that goal by a few pages.

However, having a page count goal will force you to embrace the Less Is More mantra that all screenwriters need to master.

Read ScreenCraft's Why Every Screenwriter Should Embrace "Less Is More"!

What's Making Your Script Too Long?

Experienced script readers (assistants, studio readers, story analysts, managers, agents, producers, development executives, studio executives, etc.) know when a script is too long. And it often has nothing to do with this one page equals one screen minute rule.

There's a reason why anything over 120 pages is often a sign that the script is too lengthy — because, in the context of the material coming from novice screenwriters, the script is usually that long due to the:

- Overwritten scene description

- Overwritten dialogue

- Redundant scenes

- Unnecessary scenes

Why Longer Scripts Are Frowned Upon

There are also objective reasons longer screenplays are frowned upon.

90-minute movies (give or take) fit streaming modules or allow the distributors to get as many theater screenings in a single day as they can.

Also, longer scripts often mean higher budgets, longer shooting schedules, etc.

And there are structural reasons as well.

Since screenplays are blueprints for movies — and most movies are generally 90-120 minutes long (give or take) — there's a necessary page count structure that comes into play. And going significantly lower or above that 90-120 page range means that red flags are instantly tripped for industry insiders reading your script.

Read ScreenCraft's 5 Easy Hacks to Cut Your Script's Page Count!

30/30/30 Structure Breakdown

When you have a 90-page script, breaking down general structural dynamics regarding story flow is easy — a 30/30/30 barometer breakdown.

- 30 pages for the first act.

- 30 pages for the second act.

- 30 pages for the third act.

That's an easy barometer screenwriters can work from when they first start.

Fine-Tune Your Breakdown

Now, the first act isn't going to be a third of the script. You want to get those characters into the second act quickly, which has them dealing with the conflict at hand.

So you shift it.

- 20 pages for the first act.

- 40 pages for the second act.

- 30 pages for the third act.

And you can shift that page count for each act with more or fewer pages.

Focus on Writing Sessions, Not Hours

The notion of sitting down for eight hours a day and writing is a false one. Nobody is sitting there for eight hours straight, typing away non-stop. This is a claim that you'll often hear from pundits and successful authors telling tales in interviews and panels. And it creates negative residual expectations that newcomers put on themselves.

You don't need to write for multiple hours every single day. You don't even need to write every single day. And since you're not yet a professional screenwriter, we hope this is a very liberating realization for you!

With that in mind, we suggest that you focus on writing sessions over the number of hours you write. Doing so will help you to focus on writing throughout the week with the freedom of being able to take hours and days off to visualize, take care of your family needs, cover your work shifts, get your homework done, etc. — all while staying focused by finding those open blocks of time when you can sit down and write.

- Some writing sessions may be just for an hour.

- Others may be for multiple hours when you have a day off.

- You may have a day or two in between writing sessions.

Choose a Writing Process with a Focus on Achieving Goals

The key element for a writing process that utilizes writing sessions is the output. Each writing session — no matter how long or short it lasts as far as minutes or hours — must provide written pages.

In ScreenCraft's 10-Day Screenplay Solution: How to Write Lightning Fast, you're offered a proven professional process that helps you get that first draft done in just ten writing sessions.

Goals within that process include:

- 10 pages per writing session, which averages out to a page count goal of 100 pages (allowing you to be over or under by a few).

- A rewrite-as-you-go process that helps to lessen the work necessary for your eventual rewrites (see below).

Benefits of Being Goal-Oriented Rather Than Hustling Hours

Focusing less on the hours you put into your script, and more on the product of the writing sessions you can work into your schedule will help you be able to write more like a professional working under Hollywood contract deadlines.

- You'll be able to conjure dialogue, scenes, and visuals faster.

- You'll be able to work within your family and business schedule.

- You'll take the weight off of your shoulders, as far as unrealistic writing time expectations.

4 Essentials You'll Want Your First Draft to Include

Some guidelines as you write the script include:

- Get to the concept and story within the first few pages.

- Let your characters' backstories and characterization appear through their actions and reactions to the conflict thrown at them in the second act.

- Introduce evolved and new conflicts every few pages to keep readers and the audience invested in the story.

- Build to both a physical (outer) and emotional (inner) climax.

How to Write the Beginning, Middle, and End of Your Script

The Opening Pages

Most of the time, the first few pages are all you get to impress a reader or studio exec, so you better make them good. Luckily, we have some advice on how to hook anyone in your screenplay's opening pages, including building intrigue, setting up plot points, and holding off on introducing too many character details.

The Middle of Your Script

If you're struggling with the middle of your script, join the club. This is a notoriously treacherous part of any script, but we've laid out several ways to master the middle of your screenplay, like starting the second act early, raising the stakes, and writing twists, turns, and misdirects.

The All-Important Ending

And finally, if you want to end your script like a pro, we've got some tips. These tips are less practical than the previous ones we shared above, but they're still important and create a huge impact. A few things you'll need to do in order to master the ending of your script are know the ending before you start writing, connect the dots for your audience, and create internal barriers between your characters and the end.

The Rest is Up to You

When it comes to writing your first draft, the rest is up to you. The steps provided thus far — as well as the links to other helpful tutorials — are all that you need to make the writing of your first draft happen.

Still lost? That's okay! Read What Screenwriters Can do When Lost in the First Draft!

Before you begin, for a master list of what NOT to include in your script, Read ScreenCraft's 75 Things You Shouldn't Do When Writing a Script!

How Long Does It Usually Take to Write a First Draft of a Script?

Most beginning screenwriters take upwards of six months to multiple years to finish a single screenplay. When you become a professional, expectations change, and you're forced to adhere to first-draft deadlines that only give you anywhere from 4-12 weeks — sometimes less.

It's best to begin to learn how to write under contract deadlines because you're future-self will appreciate it. But we also know that everyone has their own tendencies. The idea is to take what we offer below, meld it with what you can and can't do at this time, and come up with the perfect hybrid process that best prepares you for what is to come when this screenwriting dream comes true.

Step #8: Take a Writing Break

Let's discuss a vital element within your writing process — the writing break.

A writing break is a pause in work. It may be for minutes, hours, days, weeks, or months (we'll cover everything below). Regardless, it's where you step away from the computer or laptop and disengage yourself from the task at hand.

Robert Pozen, senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management and author of Extreme Productivity: Boost Your Results, Reduce Your Hours, told Fast Company:

“When people do a task and then [take a break], they help their brain consolidate information and retain it better. That’s what’s happening physiology during breaks.”

Most productivity researchers agree that breaks are vital to all working shifts. It allows you to refresh and re-engage in the task at hand.

Learning about breaks is applicable to the previous discussion about focusing on writing sessions over hours. But we'll also discuss the importance of taking a break after you finish your first draft.

Screenwriting Breaks By Minutes

Productivity researchers offer excellent breakdowns of an ideal number of minutes of productive work.

Pozen comments:

“Don’t think of breaks in terms of taking a set number a day, such as 12 or five. The real question is, what is the appropriate time period of concentrated work you can do before taking a break?"

There are a few different professional suggestions regarding the minutes of breaks when it comes to productivity.

75 to 90-Minute Writing Sessions

Pozen states that working for 75 to 90 minutes takes advantage of the brain's two modes:

- Learning or Focusing

- Consolidation

Kevin Kruse, author of 15 Secrets Successful People Know About Time Management, points to the work of Tony Schwartz, founder of the Energy Project. Schwartz coined the practice as a pulse and pause process, essentially expanding energy of productivity and then renewing it.

"His research shows that humans naturally move from full focus and energy to physiological fatigue every 90 minutes."

Yet how do most battle that fatigue? Kruse says:

"We override them with coffee, energy drinks, and sugar… or just by tapping our own reserves until they’re depleted."

Instead of burning yourself out by depleting your natural reserves or masking your fatigue with sugar and caffeine, you can simply, yes, take a break.

75 to 90 minutes can be a very productive writing session.

52-Minute Writing Sprints

Most novice screenwriters usually write as their secondary (or third) focus during each day.

- Most have day jobs.

- Some have multiple jobs (including school).

- And don't forget family duties as parents or siblings.

If you can't get a full hour and a half fit into your busy day, maybe a shorter writing session of 52 minutes is a good option. Finding under an hour of writing time before your day starts or before your day is about to end is a bit easier than finding a full 90 minutes.

The software startup, Draugiem Group, used a time-tracking app called DeskTime to track productivity. The study showed that working in 52-minute sprints (with a 17-minute break in between) increased productivity.

"The reason the 10% most productive employees are able to get the most done during the comparatively short periods of working time is that they’re treated as sprints for which they’re well rested. They make the most of the 52 working minutes. In other words, they work with purpose."

And that's a fantastic point, as far as looking at your writing sessions as sprints. When you have more time, that just means more time to procrastinate and let your mind wander. There's an urgency to the session when you have under an hour. You write with more purpose.

25-Minute Bursts

And then there is the Pomodoro Technique, developed by Francesco Cirillo, who named it after the tomato-shaped kitchen timer he used. His technique focuses on short bursts of work in 25-minute intervals with five minutes of break in between.

This technique is more well-suited for single tasks that require complete focus. For screenwriting, you can use this technique to focus on the following:

- Conjuring a specific scene.

- Rewriting a particular sequence you've been struggling with.

- Polishing the dialogue of a critical scene.

These 25-minute bursts can be used a la carte throughout your whole day.

- You can utilize short bursts during your work shifts during lunch breaks.

- You can fit in a short burst of writing during breakfast before your day shift.

- You can get another writing burst in before you head to bed.

The point is to find the best session, sprint, or burst time for you within your schedule and situation — while always making sure that you have an extended break in between.

If you're on a professional assignment with a tight deadline, your burst may actually have to be 75-90 minutes, with your sprint as a couple of hours and your writing session consisting of a few hours.

Screenwriting Breaks By Days, Weeks, and Months

Taking a break from your screenplay is vital to the creative process. As mentioned before, when you step away from your writing sessions, you're helping your brain consolidate and retain information better. As you go about different business and leisure during your breaks, your brain constantly tries to process the information and visuals you've had running through your head during your writing process.

- It's putting pieces together.

- It's making sense of the scenes, characters, actions, and location.

- It's processing a consistent tone, atmosphere, narrative, and voice.

When you walk away from the screen, your mind is still writing. When you come back, it's refreshed and rejuvenated.

Day Breaks

Another popular myth is that you need to be writing every single day. You don't. In fact, it's probably better that you work in full days off from writing, whether it's a couple of days during the week or taking the whole weekend off.

Remember, you can still be "writing" on these off days.

- Visualize your next scenes during daydreaming, driving, walking, running, exercising, etc.

- Figure out options for potential twists and turns (and their story ramifications).

- Replay scenes you've written and see if they play out visually.

As we've discussed, writing isn't necessarily typing. Since screenwriting is for a visual medium, you should see these scenes and moments in your head before you type them onto the page.

Spreading your writing sessions out between day breaks can be highly effective for your visualization and story/character problem-solving.

Week Breaks

You don't want to take weeks in between writing sessions. It'll take multiple months to write a single script, and it's best to train yourself to write like a professional under contract deadlines (generally 4-12 weeks for the first draft).

Week breaks are more reserved for breaks in between drafts. When you finish a draft of your script, the worst thing you can do is go right into the reviewing/rewriting process. You've already spent one-to-three months writing your first draft. If you dive back into it, you're going to start suffering from paralysis of analysis.

Once a draft is complete, take some time away from it. How much time you take will depend on your situation.

- If you're writing on spec (not under contract), take a couple of weeks away from your script.

- If you're writing on assignment through a strict deadline, work in a week where you can step away from it.

What does this accomplish? You can revisit the script with fresh eyes by doing a full review through a cover-to-cover read. Experience the script not as the writer amidst deadlines but as a script reader looking for a good read.

When you take these week(s) long breaks, you will see every glaring issue with your script that you couldn't see during the initial writing process.

All of that and more.

Stepping away for a week or two between drafts will be a true difference-maker in your script and rewriting process.

Step #9: Rewrite

Congratulations. If you've gotten to this step in your screenwriting process, you've finished that first draft. That's an accomplishment a majority of people with a screenwriting dream never attain. But you're not done yet.

Congratulations. If you've gotten to this step in your screenwriting process, you've finished that first draft. That's an accomplishment a majority of people with a screenwriting dream never attain. But you're not done yet.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote:

"The only kind of writing is rewriting."

Screenwriters traditionally hate the rewriting process. They are so close to their work that they often believe that their first drafts are perfect and ready to be shopped, packaged, and produced. We get it. There's excitement. You're thrilled to be done. You want to celebrate and then show your creation to the world.

Why Rewriting is So Important

This is a big reason why the previous step — the break — is vital to your process. When you come back after a couple of weeks or more away from your first draft and then sit down to read it cover-to-cover, you'll see those glaring issues we mentioned above.

The rewrite process is where you truly find your cinematic story. This is the time when you meld your storytelling skills and talent with a keen eye for editing.

- You need to be objective.

- You need to step outside of your own skin and be your worst (or best) critic.

- You need to read a scene or line of dialogue and realize that it just doesn't belong.

- You need to see each and every flaw of the script, big or small.

What Gets Cut During Rewriting?

Part of the rewriting process includes killing your darlings.

Those darlings may be:

- Lines of dialogue

- A fun, dramatic, or exciting scene

- A supporting character

- A visceral moment

- An eye-catching visual

No matter how much you may love them for whatever reason — and no matter how much quality they represent as a singular element — make no mistake, you WILL need to kill many darlings for the better of the overall script.

You cut dialogue, scenes, sequences, and even characters out to:

- Increase pacing

- Improve scene flow and clarity

- Center more focus on your protagonist

- Remove clutter and unnecessary story, character, and dialogue elements

Different Rewrite Processes You Can Apply

There are many different approaches you can — and need — to take for an effective rewrite of your first draft.

One habit you can utilize during the writing of your first draft is the rewrite-as-you-go process we mentioned above.

Let's say you walk out of your first writing session with 10 pages. During the second writing session, you begin by reading those first 10 pages. As you do, you rewrite and tweak those 10 pages, going through mini-versions of the processes we feature below.

- Fixing typos

- Cutting down description and dialogue

- Shortening scenes (if not deleting them)

- Working on pacing

Then during that second writing session, after doing the above, you write on.

After that second writing session, maybe you have written another 10 pages — which amounts to 20 total thus far.

During the third session, you again read what you've written — 20 pages beginning to end — and rewrite them as you go.

You repeat this pattern as you write that first draft.

The results? By the time you write FADE OUT at the end of the draft, you'll have a much more focused, tight, and flowing first draft of your script.

The Benefits of Rewriting as You Go

Added benefits include:

- More consistent tone

- Amazing pacing

- Fewer plot holes

Because each time you sit down and write may find yourself in different moods, the rewriting-as-you-go process help to reign everything in each writing session. You're reading what you wrote before, which allows you to stay on that course of tone, atmosphere, pacing, and overall consistency as you continue on. It's like watching your movie in progress, and then continuing on with the new pages after you've watched it.

Revisit ScreenCraft's 10-Day Screenplay Solution: How to Write Lightning Fast for more on that!

Overwriting Check

Overwriting can come in the form of many different areas and elements of your first draft.

- Lack of white space in your script.

- Overly long scene headings.

- Multiple camera directions.

- Overly detailed scene description.

- Overly detailed wardrobe description (not your job).

- Too many adverbs and fancy vocabulary (keep it simple)

- Overly specific action sequence description

- Redundant or unnecessary scenes and dialogue

Read ScreenCraft's 7 Signs You're Overwriting Your Screenplay!

The Less Is More mantra we mentioned above needs to be solidified during the rewriting process. You want a final draft that offers visceral and cathartic scenes and moments, by way of simple and straightforward delivery.

Read ScreenCraft's 10 Amazing Screenwriting Examples of "Less is More"!

Revising Check

Depending upon your own writing process, habits, and tendencies, revision is an organic undertaking that can be a day-to-day or a draft-to-draft task — preferably both.

It’s different from editing or proofreading (see below) because the choices that are being made — and the things that you are trying to figure out — affect the big picture of your feature film.

- The structure

- The story

- The Plot

- The characters.

During the revising of your script, you don’t want to be caught up in the details of editing and proofreading. You will lose your focus on what the revision is really about — the structure, story arcs, plot points, and character arcs. You can also include pacing, theme, tone, atmosphere, and catharsis to that as well.

Revise Using Your ARMS

To understand revising, you can use the ARMS acronym to ensure that you are staying on that revision course throughout your writing process.

Add — Adding sentences and words to your scene description and dialogue to tell your story better.

Remove — Removing sentences and words from your scene description and dialogue to better embrace the “less is more” mantra of screenwriting.

Move — Moving sentences and words from your scene description and dialogue to create better pacing, structure, and flow.

Substitute — Substituting words and sentences for new ones to create better syntax, articulation, and style.

Editing/Proofreading Check

Once you’ve managed to revise your screenplay through writing sessions and multiple drafts, it’s time to polish that script by eliminating those inescapable and annoying spelling, grammar, and punctuation mistakes that still linger within your pages.

You accomplish this by proofreading your story with your eyes specifically scanning for those types of errors. During this process, you need to avoid having revision in mind because you will surely miss multiple technical mistakes if your mind keeps wandering to structure, story, and character revisions.

Revise Using Your CUPS

To stay in the proper frame of mind, remember to use the CUPS acronym to keep you focused.

Capitalize — Capitalizing names, places, titles, months, and other elements. Example: If you’re writing a military script, lieutenant should be Lieutenant (titles).

Usage — Making sure that the usage of nouns and verbs is correct. Example: “Have you packed your luggages?” is incorrect. The correct version would be “Have you packed your luggage?” While this example may seem extreme and silly, you’d be surprised how many mistakes like this are found in submitted screenplays.

Punctuation — Making sure punctuation is correct by checking periods, quotes, commas, semicolons, apostrophes, etc.

Spelling — Spellchecking all words and looking for homophone mistakes. Homophone Examples: Your and You’re. New and Knew. To and Too. There, Their, and They’re. Its and It’s. Then and Than. Effect and Affect. Cache and Cachet. Break and Brake. Principle and Principal. Breath and Breathe. Rain, reign, and rein. By, buy, and bye.

Locate Plot Holes

There are generally five types of plot holes found within screenplays. Let's keep it real and point out that no script is bulletproof when it comes to plot holes. But to get to the best final draft possible, you should do your best to find and fill the ones you do see.

1. MacGuffin Plot Holes

MacGuffin Plot Holes are those that relate directly to the MacGuffin, which are the goals, desired objects, or any other motivators that the protagonist (and often the antagonist as well) is either tasked with pursuing or drawn to pursuing, for whatever reasons. Not every cinematic story utilizes a MacGuffin. But if yours does, know that they are the motivating element that exists only to drive the plot and is usually the cause and effect of each character's conflict that they are dealing with throughout the story.

You, the screenwriter, don't need to explain every little aspect of MacGuffins if you're going to use them. However, you want to ensure that you keep a keen sense of logic when developing them. In the end, the sole purpose of the MacGuffin is to get the story moving forward for the characters. According to Alfred Hitchcock himself, the characters care about the MacGuffin — the audience generally doesn't.

2. Logic Plot Holes

Logic within a screenplay is what you, the screenwriter, decide. But know that the power of choosing what is logical and what is not within your script can and will dictate how invested audiences will be.

- If you set your script within the real world, keep it real.

- If your script is set within the real world with the caveat of consistent requests for suspension of disbelief in exchange for entertaining action and special effects (see most Hollywood blockbusters), have fun.

The key is to always be aware of whatever logic you are and are not willing to apply within your story — and keep it consistent.

3. Character Plot Holes

These types of plot holes also range from big to small, with varying degrees of repercussions.

Perhaps the most noticeable are those that deal with the choices that a character makes. These are often attributed to general logic, so they could fall under the Logic Plot Holes umbrella, but these are specifically attached to characters and the decisions they make. Make sure that your characters are consistent.

4. Narrative Plot Holes

Narrative Plot Holes occur when there's a gap or inconsistency in a storyline. It can directly affect the logic established within the plot, or it can be a glaring hole that halts the audience's engagement with the story as they question it.

5. Deus Ex Machina Plot Holes

The term refers to a plot device where a seemingly unsolvable problem or situation is suddenly and abruptly resolved by the intervention of some new event, character, ability, or object.

For more detailed breakdowns (and examples) of these types of plot holes, Read ScreenCraft's Do You Know the Different Types of Plot Holes?

Pepper Your Script

The best part of the rewriting process is when you get to add all of the amazing extra details, plot points, clever foreshadowing, character ticks, plants and payoffs, etc.

Ask yourself, "How can I make this even better?" with each and every:

- Character

- Line of Dialogue

- Scene

- Sequence

- Moment

Pepper and enhance every element of the script. Create those masterful plants and payoffs that the reader (and eventual audience) can experience and revisit to see that such moments were properly set up.

For example, read the screenwriting plants and payoffs breakdowns of movies like:

Script Coverage

Sometimes it's helpful to get an outside perspective. That's where script coverage comes into play as an option.

Script Coverage is a professional analysis of a screenplay, consisting of various gradings of a screenplay’s many elements and accompanied by detailed analytical notes that touch on what works and what doesn’t work within the script.

Coverage formats and grading scales vary per company. And many different screenwriting contests, consulting companies, and consultants offer fee-based professional script coverage.

Read ScreenCraft's Top 5 Best Screenplay Coverage Services!

Script consultants grade everything from concept, story, characters, dialogue, pacing, and structure.

Be keenly aware of what you should and shouldn't expect from professional screenplay coverage:

- It's a tool, not a crutch — Despite its worth, script coverage should never be used as a crutch. Too many screenwriters spend too much money purchasing coverage package after coverage package for each draft of each script they write.

- It's an opinion, not a definitive answer — Always remember that whether the coverage is favorable, unfavorable, or somewhere in between, it's just an opinion in the end. But that opinion may have some fantastic points that you should consider.

- It's for pointers, not proofreading — Don't expect a word-by-word and line-by-line proofread with your script coverage. That's not what the reader is there for. They are not proofreaders looking to "mark your script" with every grammatical, spelling, and format error from cover to cover.

- It's for Constructive Criticism, not glowing reviews — If your script is that good, they'll let you know. But don't have high expectations that the coverage will dazzle you with kudos. If you can't take the heat in the script coverage kitchen, don't pay to be in there in the first place. But understand that the ability to take notes and feedback is vital to your success as a professional screenwriter.

- It's for inspiration, not answers — Readers are there to point out what works, what doesn't, and how the market may react based on current trends and expectations. And beyond that, they are there to ask questions and offer some minor options that writers could be inspired by to find the answers they seek.

You may not agree with everything they write. They may not understand everything you write. But they are there to help guide you on the many possible paths that your screenplay could take. And remember that there is a distinct difference between the feedback you get from fee-based script coverage (or mentor and peer feedback), and script notes given to you when you're a paid professional under contract.

For a more detailed breakdown of what to expect from script coverage, Read ScreenCraft's What You Should and Shouldn't Expect From Screenplay Coverage!

And check out ScreenCraft's Free Download: How to Master the Art of the Rewrite!

Step #10: Complete Your Final Draft

Okay, you've done all of the rewrite work. Perhaps you've enlisted some professional script coverage to help you with an additional draft. Now one final question remains:

"When and how do I know if I'm done?"

When is Your Script Done Done?

The hard truth is that you haven't gotten to a final draft of your script — in the big scheme of things — until it's being produced via a director, cast, and crew.

Screenplays go through many drafts during the marketing, development, and production phase. When you get the script to managers, agents, and development executives, it's more than likely that you'll be asked to do more rewrites based on their needs, wants, and preferences.

But how do you know when your spec script is done during your initial writing process?

Once you've met your personal deadline, locked the script away for a couple of weeks or so before returning to rewrite it, read the script cover to cover after that rewrite process, and do a final polish draft, it's time to say to yourself, "It's done."

A Final Test of Doneness

The final test of knowing when your screenplay is done is to tell yourself just that.

- You, the screenwriter, have to make that call.

- You're failing yourself as a screenwriter if you leave it open-ended.

- You're failing yourself as a screenwriter if you continue to do rewrite after rewrite after rewrite.

Too many screenwriters overly rely on endless feedback from family, friends, relatives, peers, and professional script coverage. The notion that a screenwriter must get feedback ends up being overblown and misconstrued. Yes, feedback can help. Yes, it's nice to get another set of eyes on the script.

The issue is that, in the end, each set of feedback you receive is just a subjective opinion. And if you continue to seek feedback from multiple people, there's no possible way to come to one true and final consensus in everyone's eyes.

- This is what often leads to endless rewriting.

- This is how writing groups can hurt a screenwriter.

- This is where too many hands in the cookie jar can turn an otherwise great story into an utter mess.

Find one individual that you trust. Beyond that, get one film industry perspective if you can. The rest is up to you.

With that said, Read ScreenCraft's The Ultimate Final Draft Checklist for Screenwriters!

Best of luck to you!

The Last and Most Important Question Once You Finish Your Script

And here's one last question that you should consider as you wrap up this script.

What are you going to write for your followup?

- Never stop writing.

- Don't spend months trying to market this script you've just written without moving on to the next as you do.

- Go through this 10-step process again for each.

- Get to the point where you have 3-5 excellent scripts to use as writing samples.

- Market scripts as you write more and hone your skills.

Read ScreenCraft's 7 Marketing Strategy Hacks for Screenwriters!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.