Why Every Screenwriter Should Embrace "Less Is More"

There's a common misconception about script readers — and Hollywood in general — and their loathing of overwriting. Screenwriters often shake their heads when that term is brought up, often thinking that the powers that be are just being lazy readers. It just isn't so.

From the perspective of the script reader — which technically will prove to be interns, assistants, studio readers, development executives, producers, studio heads, directors, and talent — there's a concrete reason why overwriting can be the death of a script under potential consideration.

It's not about Hollywood being lazy or overly complacent. It's about the experience of the read.

The read is what decides the fate of every script and every screenwriter. It's an experience that must be taken seriously by screenwriters.

Film is a visual medium. Stories are told in pictures, accompanied by dialogue and musical score. This is vastly different from the literary world of novels and short stories where readers expect colorful and articulate description to set the stage. With film, costume designers, cinematographers, set designers, and directors will do that for the eventual audience. It's a collaborative effort, as opposed to the one-on-one relationship of the author and reader in the literary platform where the reader can expect days, weeks, and sometimes months of reading one single story. Script readers have an hour or two for each script.

In respect to the read of a script, those details aren't needed, nor are they wanted. What a script reader needs and wants is to be able to see that cinematic story unfold within their own mind's eye as quickly as possible. From a reader's perspective, there's nothing worse than reading an overly descriptive, overly articulate, and excessively wordy description. It kills the read. It halts any momentum of the story. And finally, it's frustrating because that's just not what screenplays are meant to be. Readers want and need to see the film as quickly as it would be projected on the big screen, and that can't happen if screenwriters are overwriting. Read ScreenCraft's Top 5 Things Studio Readers Really Want to learn more on that subject.

Less Is More is the best mantra that screenwriters can embrace because it serves their script so much better than overwriting, which sets too much atmosphere, too much direction, and above all, too much information for the reader's mind to process while they're trying to visualize what is meant to be a film.

The true testament of an excellent screenwriter is to be able to convey style, atmosphere, and substance with as little description needed. The same can be said for dialogue as well.

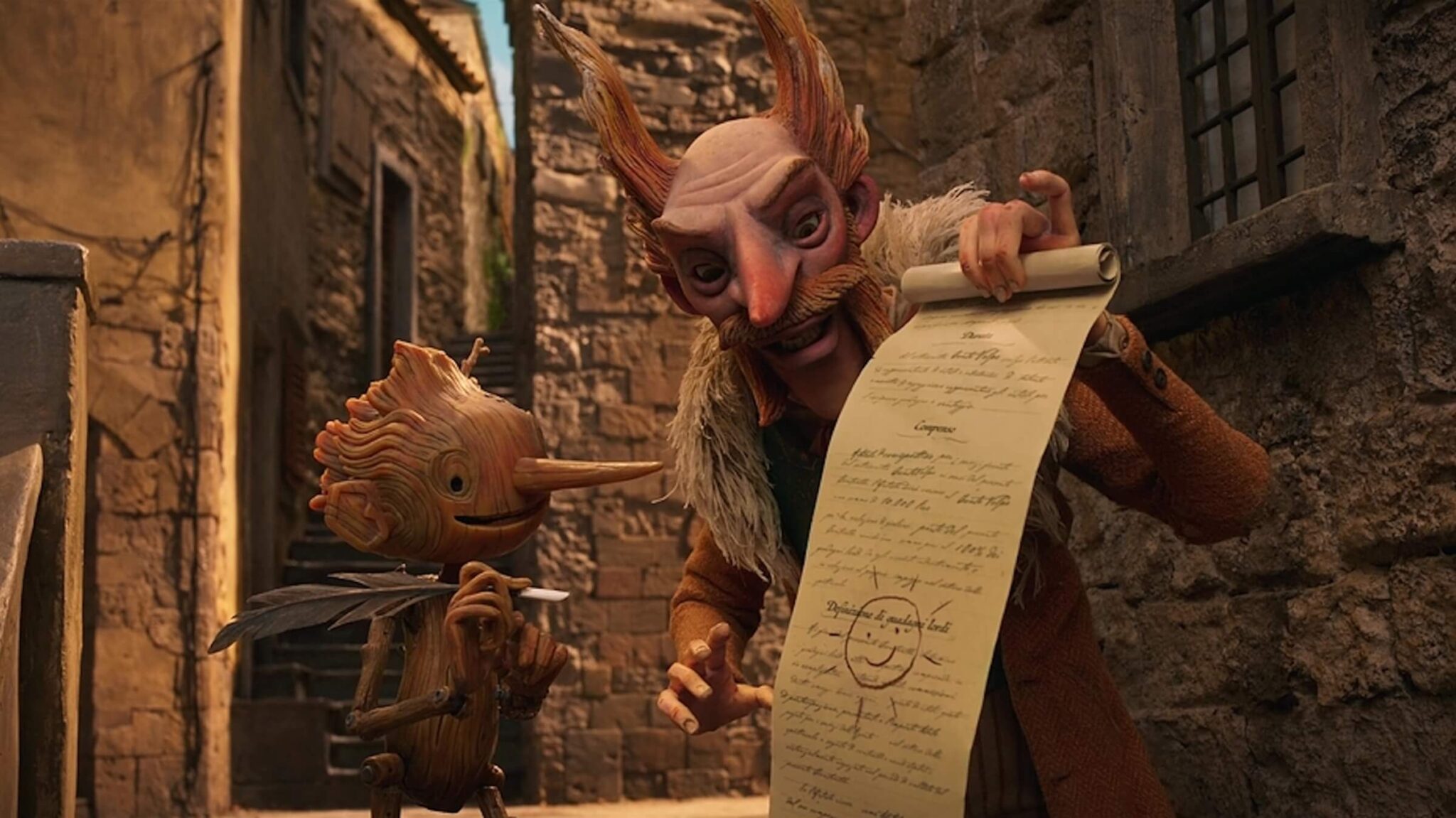

To embrace the Less Is More mantra here, we'll get right to three examples. Below are three excerpts of scenes from three different scripts — one of which went on to sign a deal with a major studio while a second garnered multiple meetings at studios and representation. We present the overwritten version of the scene first, followed by the correct version that embraces the Less Is More mantra.

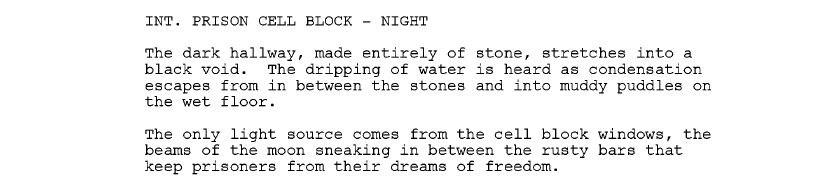

Overwritten Version

Correct Version

The overwritten version of this scene is a perfect example of what a majority of screenwriters mistakenly write. They try to create atmosphere and visual style, but it hinders the read and gives too much information to process quickly. In the end, all that the reader needs to know is that it's a dark and wet cell block.

Overwritten Version

Correct Version

There are a few elements to discuss with this example.

Specifics. When are specific locations and dates really needed? All too often in scripts, you can find specific locations (buildings, parks, etc.) and specific dates (day, month, year) that just aren't needed. Unless Hisarak, Afghanistan and April 3rd, 2008 are specifically integral to the location and time of the story (in this script they were not), there's no need to mention them.

Less Is More applies to this case because with the correct version the reader doesn't have to time log nor struggle to visualize a specific location. Obviously, in Saving Private Ryan's case, the date and location is necessary and serves a purpose due to the historical significance. In this script and so many others, they are not.

It may sound trivial and nit-picky, but you would be very surprised how often specific locations and dates are used for no particular reason. It's a waste of space.

In short, only offer specifics if they are integral to the story.

Furthermore, the overwritten version of this scene just articulates too much. It's unnecessary filler. There is a place for that from time to time but in the end, all the reader needs to know is that they're in present time Afghanistan with a shattered village in the distance. Four words — Afghanistan, present, shattered village — say so much more and immediately imprint an image for the reader's mind to comprehend quickly.

Sure, it's only a sentence or two extra, but when you're overwriting throughout your whole script, not only does it add up to too much and slow the read of your script down drastically, but it also forces you to have more pages than you really need in the end.

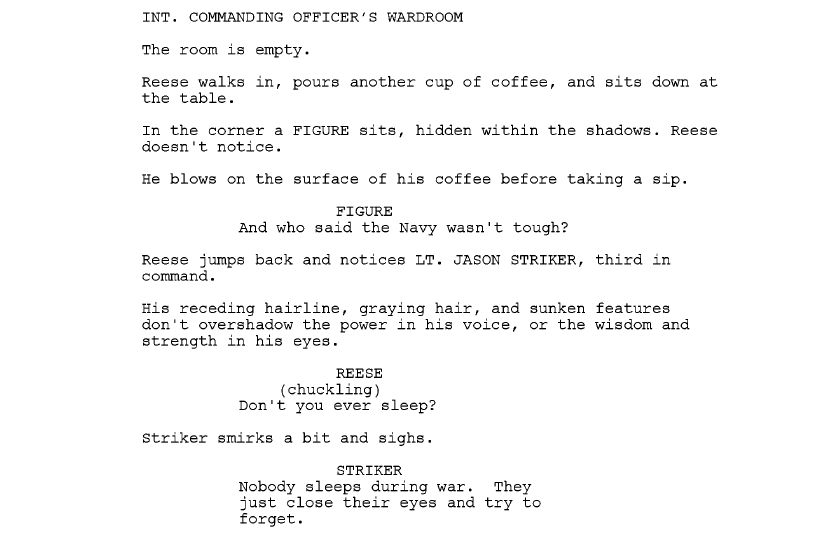

Overwritten Version

Correct Version

Here we have an example of not only overwritten scene description but also dialogue.

First off, the overwritten version of this scene opens with unnecessary filler in the scene description. We don't need to know the positions of chairs, and we don't need to be told that there's not a soul in sight. All we need to know is: The room is empty.

Set decorators and assistant directors will take care of the layout of the chairs. Before production, the script reader can obviously picture what an empty submarine wardroom would look like. Don't give the reader's mind even a moment to linger with unnecessary description. Unless those chairs being askew is integral to the story, we don't need to know in the form of the script content.

Furthermore, actors and directors will dictate the particular movements of the actor in the shot. In the overwritten version, we really don't need to know that he grimaces and what not. In the correct version, him blowing on the hot coffee, followed by the line of dialogue, stipulates the moment of the image of an otherwise tough submarine commander blowing on his coffee because it's too hot. That's all we need. It's short, sweet, and to the point.

Dialogue-wise, you can easily see that there is a significant difference between the two versions of this scene. The overwritten version is very representative of the screenplays that script readers read these days from newcomers. So much of it is too on-the-nose and so much of it is just not needed.

And Here's a Little Secret

Readers — which include studio readers, interns, assistants, development executives, producers, etc. — have a lot of scripts to read. There's no getting past this truth, and there's no sense complaining about it. They have a lot to read. So a majority of the time, they will be skimming.

But this isn't the type of skimming where they are skipping multiple pages (unless the script is really bad). Skimming is a form of reading that all script readers master. It's more so about speed than it is about skimming actually. Most quality readers can read fast this way and pick up most of the details of the script, and note that this is primarily used for scene description rather than dialogue.

So if we know that this is a truth, and we know that there's nothing that can be done about it, then wouldn't it be beneficial to all screenwriters to embrace and master the mantra of Less Is More?

The above correct versions of the script excerpts are perfect examples of this mantra. The details in the scene description, in particular, are short, sweet, and to the point. Readers can read the script fast and even more important, they can see the film through their mind's eye at a much quicker pace without losing details and momentum because the scene visuals are so accessible due to scene description that is again, short, sweet, and to the point.

It's Not About Aesthetics vs. Story and Style

Many screenwriters scoff at this notion of writing less for the sake of the reader and fear that they would be sacrificing story and style in place of aesthetics. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Less Is More mantra serves the story and style for the better of the screenwriter and their script.

Sure, there are plenty of times when finer details and more articulate sentences are welcome. You can find one or two in the correct versions of the script excerpts above. Sometimes more is needed. Readers understand that. Where screenwriters go wrong is doing so on nearly every page with almost every block of scene description.

How to Master the Mantra of Less Is More

The best practice is for screenwriters to read through their finished scripts with the goal of taking their page count down as much as possible. If you're at 120 pages, shoot for 110. If you're at 110 pages, shoot for 100. You may not make the full goal, but what this will force you to do is to pay extra attention to each and every line of scene description and dialogue.

Ask yourself:

What can I delete that doesn't affect the point of the scene?

Does this need to be here?

Can I communicate this visual with one or two words instead of one or two sentences?

What is the literal way to describe this vs. the articulate way?

Does the character need to say this?

Continue to pick away at your script, deleting lines of scene description and lines of dialogue. You can take it further by questioning each and every scene in your script as well. Great screenwriting is about cutting away the fat and presenting the meat of each and every element within the script. It serves the script so much better to whoever is reading it. It's more accessible. Your concepts and characters are more evident than ever before because they are front and center, void of being clouded by overwriting. That is why less IS more.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter and Facebook!

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!