Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey Part 8: The Ordeal

We dive into this archetypal story concept, according to Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey and Christopher Vogler's interpreted twelve stages of that journey within his book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers?

Welcome to Part 8 of our 12-part series ScreenCraft’s Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey, where we go into depth about each of the twelve stages and how your screenplays could benefit from them. Before we dive in, be sure to download our free e-book while it's still available:

The first stage — The Ordinary World — happens to be one of the most essential elements of any story, even ones that don't follow the twelve-stage structure to a tee.

Showing your protagonist within their Ordinary World at the beginning of your story offers you the ability to showcase how much the core conflict they face rocks their world. And it allows you to foreshadow and create the necessary elements of empathy and catharsis that your story needs.

The next stage is the Call to Adventure. Giving your story's protagonist a Call to Adventure introduces the core concept of your story, dictates the genre your story is being told in and helps to begin the process of character development that every great story needs.

When your character refuses the Call to Adventure, it allows you to create instant tension and conflict within the opening pages and first act of your story. It also gives you the chance to amp-up the risks and stakes involved, which, in turn, engages the reader or audience even more. And it also manages to help you develop a protagonist with more depth that can help to create empathy for them.

Along the way, your protagonist — and screenplay — may need a mentor. Meeting the Mentor offers the protagonist someone that can guide them through their journey with wisdom, support, and even physical items. Beyond that, they help you to offer empathetic relationships within your story, as well as ways to introduce themes, story elements, and exposition to the reader and audience.

At some point at the end of the first act, your story may showcase a moment where your protagonist needs to cross the threshold between their Ordinary World and the Special World they will be experiencing as their inner or outer journey begins. Such a moment shifts everything from the first act to the second, allowing the reader and audience to feel that shift so they can prepare for the journey to come.

It showcases the difference between the protagonist's Ordinary World and the Special World to come. And, even more important, we're introduced to the first shift in the character arc of the protagonist as they decide to venture out into the unknown.

And it's within this unknown that the protagonist faces many tests and meets their allies and enemies — all of which define the meat of your story by introducing the conflict, expanding the cast of characters, and offering a more engaging and compelling narrative.

Once you've put your protagonist through those tests and once they've met their allies and enemies, they're going to need to Approach the Inmost Cave of the story — preparing to face their greatest fears and conflicts. This is an essential element of your narrative, allowing the reader, audience, and characters to catch their breath, reflect, review, and plan ahead for the conflict just over the horizon. And it allows you, the writer, to build the necessary tension and anticipation that you need going into the midpoint of your story.

Everything within the first act — and beginning of the second — builds up to The Ordeal, which is the first real conflict that the protagonist must face.

What Is The Ordeal?

It's the midpoint of your story where your protagonist faces their greatest conflict yet.

The protagonist has gone through the necessary trials and tribulations that prepare them for what they believe to be the ultimate test they've faced within their journey thus far — The Ordeal.

As they Approach the Inmost Cave of their story, we've learned everything we need to know about how they plan to handle the situation. But once they begin their approach, everything goes haywire. Unexpected setbacks occur. What they thought they knew was either wrong, misinterpreted, or has evolved into a far more difficult conflict than they could have ever imagined.

This is the point of the story where the protagonist and their allies (if any) face their greatest challenge thus far — usually amid great consequences. Sometimes it's life or death. Other times it's a metaphorical version of those stakes.

This is when the protagonist hits rock bottom, making them — as well as the reader and audience — feel as if they are at the dark end of their days.

Here are three ways that you can create the best Ordeal within your story.

1. Write The Ordeal as If It Was the Climax of the Story

Just because The Ordeal is the midpoint of your story doesn't mean that it can't pack a punch.

In essence, The Ordeal is a false climax.

In Star Wars — as Kenobi goes off to deactivate the tractor beam so they can escape — Luke, Han, and Chewbacca discover that Princess Leia is being held on the Death Star with them. They rescue her, survive a hopeless situation within a trash compactor, and then escape to the Millennium Falcon, hoping that Kenobi has successfully deactivated the tractor beam.

Kenobi later sacrifices himself as Luke watches Darth Vader strike him down.

https://youtu.be/sq51w34Hg9I

This sequence feels like the end of the great space opera, but it's really launching us towards the true climax to come — the Battle of Yavin as the Rebellion takes on the Galactic Empire in an epic space battle.

The Ordeal represents what the protagonist believes is the final confrontation between themselves and the conflict that has rocked their Ordinary World.

In Mission: Impossible, the plan to perform a heist within the CIA Headquarters is worthy of being one of the most thrilling heist climaxes of all time.

https://youtu.be/2zRtOpW8gOs

https://youtu.be/5BcLRnMkI7Q

But it's really just the midpoint of the story that launches us forward with even more conflict to deal with.

In The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring, Frodo and the rest of the Fellowship are forced to fend off hundreds, if not thousands, of orcs within Moria. They even have to deal with a towering cave troll. When they finally defeat the cave troll, orcs are about to overrun them until their numbers are scattered as the Balrog appears.

Gandalf fights the Balrog and casts him into a chasm. However, the Balrog drags Gandalf down with him to his apparent death.

It's hard to believe that this isn't the climax of the film.

When you develop The Ordeal within your story, write it as if it'd be the exciting climax of any other great novel or movie. When you do that, you're retaining the interest of the reader and audience through the most difficult part of your story — the second act.

And it works in any genre. The Ordeal can be a moment where the protagonist believes they are facing their greatest physical or emotional challenge. But then everything goes wrong, despite what they've learned through tests they've undergone in their journey.

2. Kill the Protagonist's Darlings

Allies and Mentors are the rock for most protagonists. They offer emotional and physical support. Mentors offer the hero the knowledge and perspective that they need to take on whatever conflict they're forced to face.

The Ordeal is all about taking your protagonist to their lowest of lows so that they can rise up and be resurrected in such a way that they can truly handle the major conflict once and for all.

And what greater way to take them as low as they can go than killing their allies and mentors.

In Jaws, Brody loses both his allies and mentors in Hooper and Quint.

During The Ordeal of that story, the shark attacks the shark cage and Hooper is thought to be lost.

Soon after, as their now sinking boat takes on water, the shark attacks and kills Quint, leaving Brody all by himself.

Note: The Ordeal in Jaws comes a little later than the Midpoint of the story. There are always variances within story structures.

Brody is now tasked with taking on the shark all by himself.

When you take away beloved characters, you create an empathetic reaction for the reader and audience. This leads to cathartic moments that make your story even more memorable and engaging.

We feel for the protagonist because we've fallen in love with these characters. We rely on them, just as the protagonist does.

Kill your darlings.

3. Give Opportunities Within The Ordeal for the Protagonist to be Resurrected

Two Hero's Journey stages away from The Ordeal is The Resurrection — The climax where the hero faces their final test, using everything they have learned to take on the conflict once and for all.

Within that Resurrection, your protagonist needs to have a moment of transformation. But before that transformation can occur, something has to push them to the brink — to their lowest point.

While losing an ally or mentor can help set the stage for the need for them to transform so that they can handle the final test, we need more. They need to lose hope, courage, or strength to carry on. The reader and audience need to feel as if there's no returning to the Ordinary World because that is how bad things are.

In Jaws, we know that Brody is afraid of the water. This character trait is showcased time and time again throughout the story. He's lost his allies and mentors, yes. But now he must face his greatest fear from his Ordinary World — the water. Not to mention the giant shark that is coming to eat him.

The Ordeal within that film sets up a necessary transformation that must occur before he can face his fear of the water and kill the shark once and for all.

Inject characterization throughout the first and second act of your script that can help you showcase a powerful transformation that will keep the reader and audience invested, engaged, and compelled.

The Ordeal is the midpoint of your story that works as a false climax, taking your protagonist to the depths of despair. It offers you the ability to create an engaging midpoint climax that takes you into the third act. It ups the stakes within your story by taking away beloved allies and mentors. And it sets up the necessary transformation that your protagonist must go through in order to prevail.

And remember...

"The Hero's Journey is a skeleton framework that should be fleshed out with the details of and surprises of the individual story. The structure should not call attention to itself, nor should it be followed too precisely. The order of the stages is only one of many possible variations. The stages can be deleted, added to, and drastically shuffled without losing any of their power." — Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers

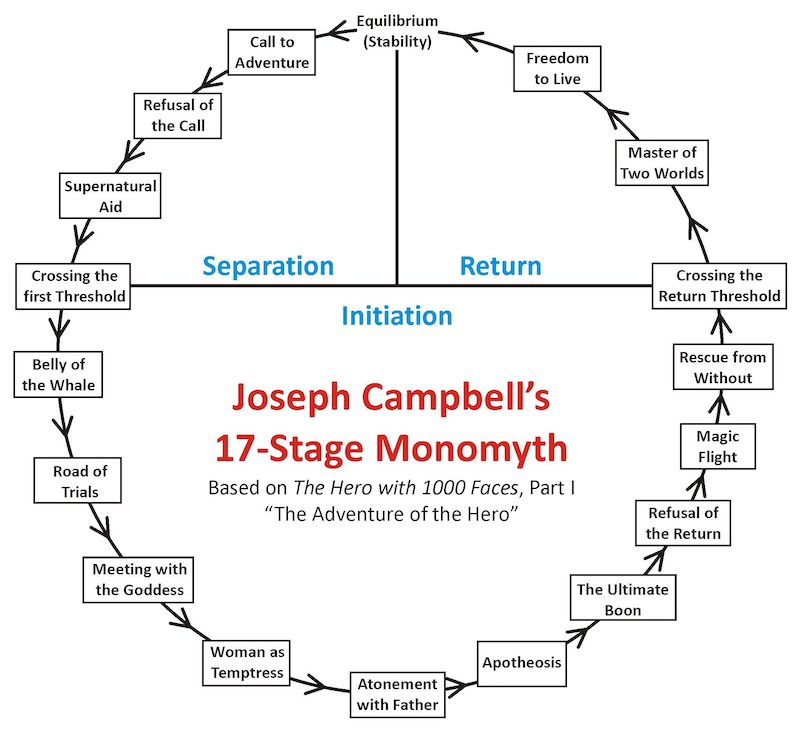

Joseph Campbell's 17-stage Monomyth was conceptualized over the course of Campbell's own text, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and then later in the 1980s through two documentaries, one of which introduced the term The Hero's Journey.

The first documentary, 1987's The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was released with an accompanying book entitled The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work.

The second documentary was released in 1988 and consisted of Bill Moyers' series of interviews with Campbell, accompanied by the companion book The Power of Myth.

Christopher Vogler was a Hollywood development executive and screenwriter working for Disney when he took his passion for Joseph Campbell's story monolith and developed it into a seven-page company memo for the company's development department and incoming screenwriters.

The memo, entitled A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was later developed by Vogler into The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters in 1992. He then elaborated on those concepts for the book The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

Christopher Vogler's approach to Campbell's structure broke the mythical story structure into twelve stages. We define the stages in our own simplified interpretations:

- The Ordinary World: We see the hero's normal life at the start of the story before the adventure begins.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is faced with an event, conflict, problem, or challenge that makes them begin their adventure.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero initially refuses the adventure because of hesitation, fears, insecurity, or any other number of issues.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor that can give them advice, wisdom, information, or items that ready them for the journey ahead.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their ordinary world for the first time and crosses the threshold into adventure.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero learns the rules of the new world and endures tests, meets friends, and comes face-to-face with enemies.

- The Approach: The initial plan to take on the central conflict begins, but setbacks occur that cause the hero to try a new approach or adopt new ideas.

- The Ordeal: Things go wrong and added conflict is introduced. The hero experiences more difficult hurdles and obstacles, some of which may lead to a life crisis.

- The Reward: After surviving The Ordeal, the hero seizes the sword — a reward that they've earned that allows them to take on the biggest conflict. It may be a physical item or piece of knowledge or wisdom that will help them persevere.

- The Road Back: The hero sees the light at the end of the tunnel, but they are about to face even more tests and challenges.

- The Resurrection: The climax. The hero faces a final test, using everything they have learned to take on the conflict once and for all.

- The Return: The hero brings their knowledge or the "elixir" back to the ordinary world.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!