Oscar-Nominated Tony Gilroy's 7 Guidelines to Writing an Original Screenplay

Tony Gilroy prides himself as an original screenwriter, despite having written adaptations during his twenty-five year screenwriting and directing career. He wrote the screenplays for the Bourne series starring Matt Damon and directed the fourth film of the franchise as well, starring Jeremy Renner. He was nominated for Academy Awards for his direction and screenwriting for Michael Clayton, starring George Clooney. He also wrote and directed Duplicity, starring Julia Roberts and Clive Owen. He has written many other successful films, including The Cutting Edge, Dolores Claiborne, The Devil's Advocate, Proof of Life, and he also produced the acclaimed Jake Gyllenhall film Nightcrawler (which his brother Dan Gilroy wrote and directed).

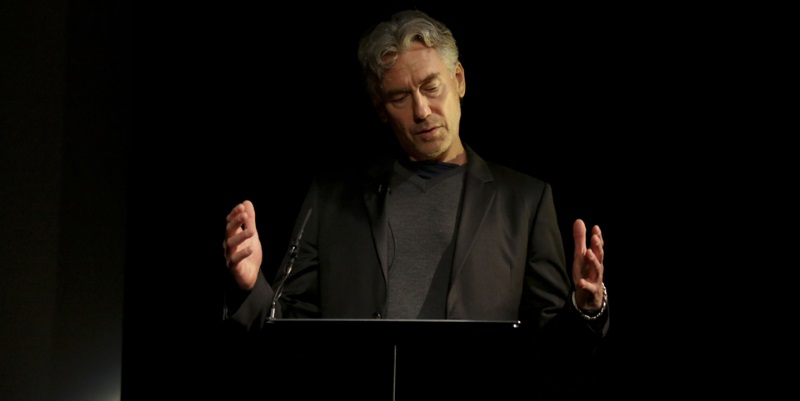

In this BAFTA Guru video, Gilroy admits that despite being a working screenwriter, the guidelines that he offers are those that even he needs to remind himself of — pointing to the fact that even Oscar-nominated screenwriters struggle as much as novice screenwriters.

We've pulled seven guidelines from this excellent speech and Q&A session — which can be watched below this breakdown — and added some further elaboration on the points that he made so well.

1. You Cannot Teach Someone to be Imaginative

Writing the original screenplay is magic. There’s no pre-existing material like there is with an adaptation or studio assignment, therefore you have to be an imaginative individual. You can’t teach that in a screenwriting course, workshop, or book. There are no secret formulas to creating original stories. It’s found within. If you’re not an imaginative person that can escape into a concept, world, story, and collection of characters and use your imagination to build on them, there’s no way you can possibly be an original screenwriter.

2. Begin with a Small Idea

Screenwriters are often taught to think big. When writing an original screenplay, Gilroy believes that you need to start small — find something small and very, very specific. The big ideas don’t work. You drown in them. However, you can have a spark that touches on big issues, topics, and events. It can be through a character, through a moment, a small point in history, etc.

Gilroy explains an example that he experienced with his script The Cutting Edge. The producer came to him and said that he wants to do Taming of the Shrew in the world of pairs figure skating. It’s a specific idea. When he worked with Stephen Soderbergh on Duplicity, the specific idea was to create a story about three scenes told from different perspectives of a couple, each of which showcase completely different meanings. With Michael Clayton, the specific idea was to do a movie about a fixer and a law firm.

Start with something small. Break it down to the core. Instead of writing the logline last when you’re ready to market it, write the logline first. Focus on small and specific concepts for original screenplays.

3. Play with It

The idea has to grow. Gilroy states that he’ll sit at his desk and just play with the idea. He’ll write scenes, dialogue, etc. Some of the material he’ll come back to. Some he’ll discard. But the thought is that you let the idea grow and you build on it. Whether if that’s writing scenes, as he did, or just going for long drives, walks, runs, or daydreaming. Let the idea grow. Play with it and see where it goes.

He goes on to say that there were so many different versions and different directions that he took with Michael Clayton — not in draft form, but in outlines or concepts. That’s story development. You have to play with the idea and see it as many different ways as possible to find what sticks. A prime example is the Matt Damon and Ben Affleck script for Good Will Hunting. It was originally written as a thriller with the government trying to utilize Will’s genius to break codes. As we know, it thankfully ended up being a character driven drama instead.

Play with the idea. Exhaust all of the possibilities until you find what version appeals to you most as a storyteller.

4. You Have to Know and Understand Human Behavior

Gilroy emphasizes this point, saying that the quality of your writing is capped at your understanding of human behavior and it will be a direct reflection of your understanding of the complexities and contradictions we humans have. It doesn’t matter what type of character you are writing for — even if they’re not human. Understanding human behavior is key in any screenwriting, but especially writing the original screenplay where you have no pre-existing material to work from.

Along with that is the need for empathy because you’re going to have to feel for those characters, live through their struggles, and be able to communicate that through the script.

5. Develop an Outline

Some writers — myself included — don’t like writing outlines. Some feel that it’s too constricting. Gilroy feels that it’s necessary in his process. He doesn’t want to be in the script format trying to discover the story. To him, it’s like wearing a tuxedo to a diner. He wants to “keep it messy” until it is ready to be in script form.

He has no strict rules for the format of the outline. It can be 30 to 80 pages, as long as it’s from beginning to end. He rightfully states that you have to know the end of your movie so that you can build to it. This is particularly important for thrillers or other scripts where you’re forced to plot things out, building to that surprising or shocking ending.

For those that don't like to write outlines, you still have to know the major story points — if not through a physical outline, then through many sessions of visualization.

Whatever outline process you have, just know the major beats of the story from beginning to end.

6. Improve the Outlined Story While Writing the Actual Script

Gilroy states that there’s really nothing that feels any better than cutting out something you don’t need that you originally thought you needed. This is the process of going from outline to script. Outlines aren’t things that you need to stick to. You should be constantly finding multiple elements to cut — and it feels good doing so.

That's what writing the script is about. It's putting the pieces together within the confines of the cinematic structure of a screenplay, and seeing what fits and what doesn't. Seeing what flows and what is slowing the story down, and then making the necessary cuts and adjustments.

Outlines shouldn't confine you, instead, they should simply be a guiding force with the freedom of always being able to change direction.

7. It's About Instincts, Not Formulas

He received a question from the audience that is quite common, referencing the usage of formulas and directives like The Hero's Journey and other such books. Gilroy quickly states that it should be instinctual, as far as what choices you make. We've all been sucking up narrative since we were born. We know more about storytelling than anything through books, television, movies, plays, and stories told to us by our parents and teachers. He even outright says that we don't need Joseph Campbell to tell us what the Hero's Journey is because we already know. It's in our DNA.

Watch this amazing lecture and Q&A with Tony Gilroy.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!