Stewart Stern: A Great American Screenwriter

Two-time Oscar-nominated and Emmy-winning screenwriter Stewart Stern died on February 2nd at 92. Though his last produced work came in 1978, the Sybil and Rebel Without a Cause architect had an amazing career, shifting dexterously between features, adaptations, miniseries and live television, and penning vehicles for some of the most iconic movie stars in history. No less than the likes of Paul Newman, James Dean, Natalie Wood, Sal Mineo, Marlon Brando, Katherine Hepburn, Tony Curtis, Eva Marie Saint, Jason Robards, Henry Fonda, Joanne Woodward, Sally Field, Martin Balsam, Dennis Hopper, Lee Marvin, Sam Waterston, Michael Moriarty, and Cloris Leachman owe some of their best roles to him.

Seminal Hollywood filmmakers like Fred Zinnemann, Arthur Penn and Nicholas Ray directed his screen and teleplays, with Ray in particular doing so to iconic result. Stern even penned the screen adaptation of Paul Newman's 1968 directorial debut Rachel, Rachel. Without a doubt, this man had an amazing career and an amazing life, and that's without even mentioning his service as a member of the 106th Infantry Division in the Battle of the Bulge and his being awarded a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star, and a Combat Infantry Badge.

Many high-profile writers including Christopher McQuarrie and Stephen Chbosky have since commented publicly on the influence Stern had on their careers and development as writers. That Stern was a magnanimous mentor (he co-founded Seattle's TheFilmSchool and taught screenwriting at USC and in Sundance Screenwriters Labs) who had a lasting influence in and on Hollywood is undeniable, but beyond that, his work speaks for himself.

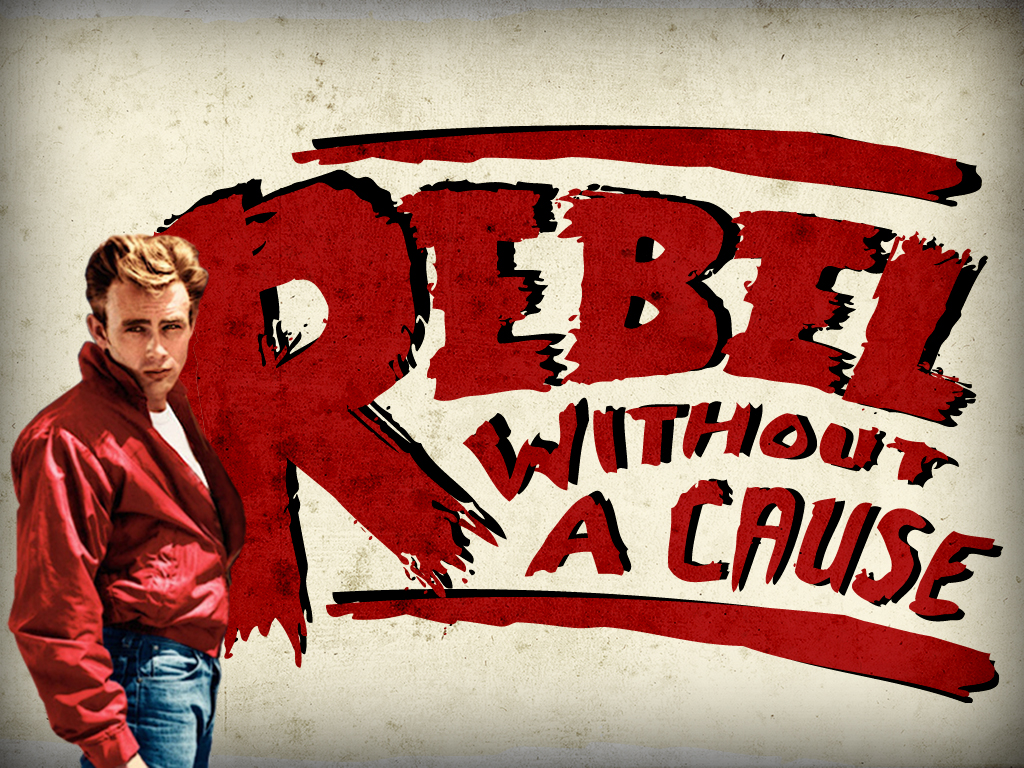

Rebel Without A Cause is mostly remembered as the vehicle that immortalized James Dean, who died tragically before the film was released. It's perhaps even more important, though, when viewed through the lens of being a screenplay produced by a major Hollywood studio in the mid-1950s. Here's why.

With the unprecedented horrors of World War II barely in the rearview mirror, and with the Allied defeat of Germany and Japan, America was eager to revert to a time of peace and prosperity (we won't mention The Korean War or McCarthyism). It was time to focus on crystallizing and cultivating the idealized nuclear family. Practically speaking, this meant a national mandate to buy, buy, buy and procreate, procreate, procreate. This meant high-tailing it to the suburbs, cruising to the soda fountain in a sleek Chevy or Ford, weekend barbecues, doing the Twist and attending every sock hop you could.

Hollywood was quick to recognize and adopt this cultural zeitgeist, with landmark television shows like The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, and Leave it to Beaver all promulgating in their own way the notion of the “normal,” idealized family unit. In those shows, the families are completely functional, loving and cherishing, and the only problems they have are the kind that can be humorously solved in 22 minutes. Saying so doesn't denigrate or dismiss those often exceedingly well-written shows, which are still celebrated and widely cherished today. And saying so isn't meant to imply that Hollywood didn't produce some daringly dark and groundbreaking films, because it did; Sunset Blvd, The Searchers, Vertigo, Touch of Evil, All About Eve, 12 Angry Men, On The Waterfront, Bridge on the River Kwai, The Night of the Hunter, The Asphalt Jungle, The Caine Mutiny and The Wrong Man all come to mind.

But Rebel Without A Cause was the film that took a sledgehammer to the idealized mythology of the perfect nuclear family and the portrayal of suburbanite American teenagers as angst-free, chipper and effortlessly upright. It was first--with The Blackboard Jungle nipping at its heels--to reflect the truth that juvenile delinquency and violence was on a monumental rise. And as was its tonal approach, the genesis of the script was unusual.

In 1946, years prior to the eventual release of the film, Warner Bros. bought the rights to psychiatrist Robert M. Lindner's book Rebel Without a Cause: The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath. The film itself, however, does not reference Lindner's book in any way. Irving Shulman wrote the initial treatment based on a 17-page story by director Nicolas Ray, for whom doing a film exploring normal, un-sensationalized juvenile delinquency was a passion project. In coming aboard and creating the screenplay, Stern drew heavily upon autobiographical elements from his past.

The resulting narrative eschews escapist, peachy-keen schmaltz in favor of exploring profound adolescent angst and the myriad of deep-seated tensions existing within seemingly ideal families. The very first scene unforgettably makes clear the acute stakes of the world, introducing adolescent principals Jim Stark, Judy and Plato all having been picked up by police--Stark for public drunkenness, Judy for wandering about in the wee hours of the morning, and Plato for--gasp!--shooting puppies. The latter would no doubt still be considered shocking in today's Hollywood.

Though Stark, Judy and Plato begin the story not knowing each other, their lives intersect intensely as the narrative unfolds. The script's opening immediately establishes that America’s youth is in serious trouble, putting a dent in the pervasive “boys will be boys” cultural mentality.

The opening is also significant from a structural perspective: because Stark, Judy and Plato are so overtly linked and defined by juvenile waywardness and angst, the script effectively positions theme as the driving force of the narrative. Rebel Without A Cause impacts primarily as a theme-driven narrative, rather than being plot-driven or character-driven. As such, it wouldn't be unreasonable to cite the the film as being, inadvertently, a precursor to hyperlink cinema, crystallized by Robert Altman with Nashville and Short Cuts and made mainstream prominent via Amores Perros, 21 Grams, Babel, Magnolia, Traffic, Crash, Syriana, The Burning Plain, etcetera.

In an active undermining of supposed 1950s American suburbanite middle-class values and image, Jim’s parents are presented as dysfunctional when they come to pick him up: the effeminate father is completely dominated by the pushy mother. Throughout the script they are depicted as quarreling and having a complete inability to connect with their son. The parents claim that they moved Jim out to L.A. to give him a fresh start. The reality is that they use their son’s problems (which are largely caused by them) as an excuse to keep moving and ignoring their own.

From there, the script keeps a tight focus on the internal conflicts plaguing Stark, Judy and Plato--and the root of those conflicts. Because Jim’s father has allowed himself to become a pushover, Stark suffers from a lack of a male role model and is alone in his quest to discover his identity and masculinity—what it means to be a man. Judy, in the throes of Oedipal conflict, aches from a lack of affection from her father, who seems unsure of how to relate to his daughter now that she has entered adolescence. Plato is perhaps the most lost and uncentered of the trio, as his father abandoned him and his mother is absent from his life. He is cared for only by the family maid, so Plato latches on to Stark and psychologically tries to assign him multiple roles: friend, father figure, and perhaps even lover.

Yes, many viewers and historians have interpreted there to be a homosexual undercurrent in the relationship between Plato and Stark. Given the Production Code and cultural climate of 1950s America, it's impossible that any overt attraction or romantic love between the two characters could have been expressed, regardless of intent. But really, this is part of the universal beauty of Stuart's script: whether by limitation or design, the relationship between Stark and Plato is ambiguous enough that one can either interpret romantic affection between them or merely view Plato's lingering attachment to Stark as further expression of his tremendous need for affection and acceptance, his need being so overwhelming that it expresses itself in a myriad of ways and on a multitude of levels.

In the final act of the script, Stern really tears into the prevailing cultural artifice of middle-class, suburban America. Jim, Judy and Plato break into a vacant house and engage in an active fantasy about what they want their family life to be. They psychologically construct their vision of what families should be like, in part through satirizing their parents’ behavioral disposition and role fulfillment. Jim and Judy become devoted husband and wife and nurturing father and mother to Plato. The sequence may seem passé and even quaint now, but properly contextualizing the script renders the writing no less than daring--a term that can easily be applied to the project as a whole.

Rebel Without A Cause is a script that levels the reader with its portrayal of violence and family dysfunction. This isn't because Stern constantly provides scene after scene of maiming, death and screaming, but because he skillfully lingers on the profound emotional impact of every instance of violence and familial discord on the principal characters. The script ends tragically but is not overtly didactic. None of the family strife is resolved by conclusion (although a ray of hope is implied). All of the social institutions in the story fail to create harmony, especially in regard to adolescents...family, school, the police and justice system…but the script doesn’t provide any concrete answers as to why.

The script doesn’t say that the generational rift between parents and their children and the failings of guiding social institutions are explicitly to blame for juvenile delinquency, nor does it point in bright lights to a solution to the problem. Rather, the script explores the notion that families and social institutions make empty promises and provide no definitive answers, and that teenagers should be open to seeking answers independently. This is the journey that Stark, Judy and Plato undertake.

Though there aren't necessarily overt external antagonists standing in their way, their quest for inner peace and the acquisition of their true selves comes fraught with alienation and the threat of permanent aloneness.

Simply put, Rebel Without A Cause is a daring, damn good and historically important script that focuses on deep-seated and universal internal conflicts. Its existence ensures that, though Stewart Stern is now gone, his talent and lasting impact as an American screenwriter will never be forgotten.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!