7 Screenwriting Lessons A QUIET PLACE Can Teach You

Warning: Very Mild Spoilers

What can the success of A Quiet Place teach screenwriters about writing suspense, horror, thrillers, and spec scripts?

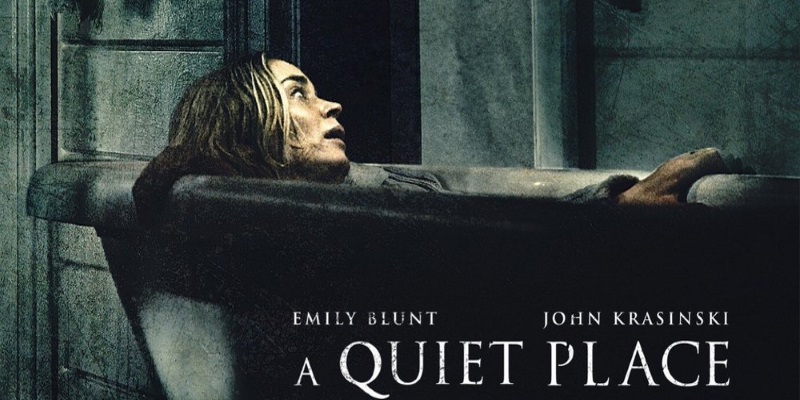

If you haven't already heard, the $17 million-budgeted film opened to $50 million at the domestic box office. Written by longtime friends and writing/directing partners Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, with a rewrite by the film's director and co-star John Krasinski, the film tells the story of a family forced to live in silence while hiding from creatures that hunt by sound.

When an original film like this debuts to high praise and big box office numbers, screenwriters need to take notice and explore the ins and outs of where such a script came from, why it drew the interest of Hollywood industry players like Krasinski and production company Platinum Dunes, and how it managed to engage both Hollywood and audiences.

Here are seven important lessons you can learn from this taut suspense thriller. And read through to the end for a quiet surprise!

1. The Spec Script Is Alive and Well

A Quiet Place is yet another example of how powerful the spec script still can be, despite the naysayers.

Read ScreenCraft's Why the LA Times Is Wrong About Spec Scripts!

For the second year in a row — see 2017's Oscar-winning Get Out — an original concept and screenplay has managed to prove that original ideas attract major studios, distributors, talent, and better yet, major audiences.

In an industry of sequels, remakes, reboots, and an undying obsession with intellectual property, original screenplays written on spec are still a hot commodity. They can lead to amazing buzz for a screenwriter. Sure, they can also lead to that unending calendar of meet-and-greet meetings throughout town with people saying how wonderful your spec is, only to make no offers to actually buy and produce it. However, if that type of thinking had stopped Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, A Quiet Place would be nothing but another spec collecting dust on the shelf.

If you think that this is all just wishful thinking and Hollywood will just treat it as a flash in the pan and go back to making endless remakes, think again.

Platinum Dunes co-founder (he's partnered with Michael Bay) Brian Fuller recently spoke with CinePop, announcing that the production company — perhaps most famous for its horror remakes of The Amityville Horror, The Hitcher, Friday the 13th, and A Nightmare on Elm Street — is discontinuing its business module of remakes.

“We’ve rebooted enough. We’ve done all of our [rebooted] horror movies. We’re not going to be doing that anymore. For us, as a company, we’re always looking for original material. And the idea of finding something original was important for us. We made a film where there’s two to three minutes of talking in the movie, where sound is a full character, and it feels like audiences are really responding to those ingredients,” Fuller stated.

While that's not an industry-wide statement, it's a pretty good start.

Spec scripts are important. Screenwriters shouldn't follow the advice of most pundits and only seek out intellectual property to adapt for the screen. Hollywood wants original material. They always have and always will. And now with the success of a film like A Quiet Place, right on the heels of Get Out, perhaps they'll widen their search even more.

2. You CAN Be Original and Unique

Concept, concept, concept. It's so important for screenwriters. Too many try to tell their versions of the cinematic stories we've been seeing for years instead of giving us something new.

You can be original and unique — you just have to put in the work to find those types of concepts, ideas, and spins on conventional stories and subgenres.

"The origins of A Quiet Place date back to our college years, as we became obsessed with the silent cinema of Charlie Chaplin, F.W. Murnau, Buster Keaton, and Jacques Tati. These filmmakers were masters of visual storytelling, needing not one line of dialogue to communicate character, emotion, or intent. Cinema had never felt so pure. But having been raised on a healthy dose of Alien, Jaws, and dozens of Hitchcock films, we wondered if you could fold the silent visual techniques of the early 20th century into the context of a modern-day genre film. And thus, A Quiet Place was born," Beck and Woods told IndieWire.

Their script could have meandered into overly familiar territory by just telling a story about a family trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic world. But they took what many could have conceived as a gimmick — the threat hunts by sound, thus the family has to live a silent life or die — and wove that into a story about a family dealing with loss and identity.

Finding original ideas and unique spins on established subgenres is no easy task, but you have to put the work in to find them. You have to look both outward and inward to question and decipher what's been done, in what different ways it's been done, and how you can bring something new to the table.

"Amidst a theatrical landscape of superhero films and IP-based properties, we’re hoping our silent film breaks through the noise. A Quiet Place was a film born out of passion with modest beginnings, and it is an understatement to say we have been humbled by this incredible journey. This project has opened up many doors that were otherwise closed," said Beck and Woods.

3. Rejection Doesn't Define Your Eventual Success

As a screenwriter trying to wade up through that dense and saturated script market, you have to take chances. You can't let your inner and outer critics tell you that something is too weird, too different, and too difficult to sell.

"While the idea felt cinematic, we thought it might come across as a gimmick. There were times we would pitch the logline to producers or friends, but they would stare back with a blank look, clearly indicating the idea was a dud. We wondered if perhaps they were right and we shelved our work."

For most screenwriters, this would have marked the end of a script as they moved onto something else. But for these two writers, the idea kept calling to them despite the critics they encountered within the industry.

"One studio exec outright passed on even reading the script after we pitched the concept over lunch."

Their representation took the unique script out to give it its fair share in the market. Because of the silent nature of the narrative, it was a strange 67-page screenplay that only had one line of dialogue.

"Immediately we determined the script must feel as cinematic as the best version of the final film. This process forced us to take an unorthodox approach to screenwriting, in which we threw formatting styles to the wind. An example: for the monopoly scene (as seen in the trailer), we photoshopped our own Monopoly board into a script page. Other times, a single word surrounded by white graced an entire page to emphasize a loud sound. Each set piece — the corn silo, the pregnancy, the nail, the fireworks, the climax, etc. — became loaded with an abundance of sonic potential... make no mistake, we knew this was a weird screenplay. We had no promise of a script sale. We figured most producers would laugh off the project by the shallow page count."

When the script made its way to Platinum Dunes, Beck and Woods were sure it would go nowhere. However, one week later, Michael Bay was attached to produce. He called Paramount and told them to make this movie.

"Days later we would receive one of the best calls of our lives. Paramount was buying the script. We dove into a rewrite based on the studio's notes, which were the antithesis of corporate creative groupthink – they wanted to preserve the fabric of this odd script. It became clear that Paramount was treating this project with care... and just when we thought this journey couldn’t get crazier, we received another call from our agent, right before Election Day 2016: 'Guys, John Krasinski read the script and loved it. He gave it to Emily Blunt and she flipped for it. They both want to star in it and John wants to direct. Cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen wants to shoot it. Paramount is dating the film for April 2018. And the studio wants to give you a blind write-to-direct deal.' Our spinning heads had fallen off. We were so used to hearing 'no, sorry, not for us' and now it was only 'yes, yes, yes.'"

Believe it or not, this can happen to you. Sure, it takes some luck and a lot of hard work — there's no getting around that. But in an environment telling you that nobody wants your original work, that it's all about IP, and that studios only want to churn out the same thing over and over to audiences — A Quiet Place proves that this just isn't so.

Rejection doesn't define who you are as a screenwriter and what type of success you may or may not have. It should fuel you to push harder in an industry that has trained itself to reject you for blind self-preservation. It should be something you learn from as you adapt and continue on.

4. Show the Stakes Early

Within the first few minutes of the film, the script manages to showcase just how high the stakes are. When this is revealed, the rest of the film is filled with a dangerous atmosphere that keeps the audience engaged and on the edge of their seats. Anything can happen.

A Quiet Place is a perfect example of how to craft an engaging horror and suspense thriller. It's not just about scares and things jumping out at you. It's about building the anticipation with each moment after you've told the audience — through your characters and opening moments of your story — that anything is possible. No punches are going to be pulled.

When you raise the stakes of your script early on, it fuels the story, the characters, and the concept. Don't waste time with slow burns and setting up atmosphere and tone within those first few pages. Slap us in the face and have your script say to us, "Yep, shit's going to get real from here on out so pay attention."

Read ScreenCraft's Must-Read Analogy That Teaches “Raising the Stakes” in Screenplays!

5. The Power of Show, Don't Tell

"Writing a silent movie isn’t easy. You can’t use dialogue as a crutch. And you can’t bore the reader with blocks of description. We hit our heads against the wall trying to break the story and silence the voices of everyone who said this idea wouldn’t work," Beck and Woods told IndieWire.

The power of this screenplay and eventual film lies within the subtleties of showing versus telling. With the concept of characters not being able to openly speak, the screenwriters were forced to embrace the notion of having to rely less on bad expositional dialogue and more on allowing what the audience sees to delve into the details of the world, the situation, and how dire the circumstances really are.

In the first images of the film, we see the importance of silence as the family maneuvers through the deserted town in search of supplies. We read the news headlines of magazines and newspapers that reveal key details and exposition. We see the tactics that the characters are forced to utilize in order to remain as silent as possible to avoid detection from the as-yet-seen threat.

As the story goes on, the script showcases the power of the "show, don't tell" screenwriting mantra — perhaps more so than any other contemporary screenplay ever written.

Watch the film and pay specific attention to how visuals, actions, and reactions are all that you need to tell a cinematic story.

6. Small Story Windows

With the exception of the time jump from the opening sequence, A Quiet Place only accounts for a couple of days in the lives of this family.

The element of telling a story using small story windows offers the reader the opportunity to have less to remember and envision. And when they have less to remember and envision, they can more easily experience the cinematic core concept and story that you tell.

The more you add to the premise, the greater the risk you will face of losing the reader.

Instead of having your screenplay tell the dramatic story of your alcoholic character trying to go sober over the course of a year, why not focus on the last day of the last step in their 12-Step program?

Instead of having your screenplay tell the epic story of a historical World War II battle, why not focus on one soldier as they deal with the overarching conflict?

Instead of having your screenplay tell the horrifying story of a serial killer stalking and killing multiple victims, why not center the story on a single victim in their house watching the news reports of the killings and then hearing a floorboard creak from above?

In A Quiet Place, we never learn how this strange event that seemingly wiped out much of humanity happened. All that we witness are a couple of days and nights in the characters' lives.

In a lesser screenplay draft or final cut, we could have been presented with bookends that over-explain the concept and situation. We could have seen where this family came from and where they ended up. Instead, we experience just a small window of time that allows us to be engaged by the suspense at hand without suffering through the details. The film is 90 minutes long in an industry that often pushes the limits of how long an audience's interest can be engaged. Most films are two hours to two and a half hours long. Less is more.

7. Concept Is Great, But It's Nothing Without Even Greater Stories and Characters

A family surviving an alien invasion — great. They can't make any sound because the aliens are attracted by it — great. But A Quiet Place is so much more than that. It's a story about a family dealing with loss and estrangement.

"It transcended any genre. While it may have been perceived as a horror film, you can’t get to these numbers without it being about story," Kyle Davies, Paramount’s president of domestic distribution, told Deadline. 'The movie became all things to all people; it connected with people’s primitive needs to protect family in a dangerous time."

That is what the whole story centers on. A mother and father wanting to protect their children. Each of them attempts that in different ways. And each of their children reacts to that protection in different ways as well.

Without those family dynamics to drive the story and concept, the sound factor — or lack thereof — would be nothing more than a gimmick.

"A Quiet Place wasn’t just a fun concept. It’s a metaphor for the breakdown of family communication," stated Beck and Woods.

When you find that great original concept, the next part of your job as the screenwriter is to use that concept as a platform to tell personal stories that will resonate with audiences on an equally personal level. Had the characters in the script and film been a traveling bunch of twenty-somethings connected only by drinking and partying, the story wouldn't have grasped the audience's heart like A Quiet Place did.

The wonderful thing about genre writing is that you can mask a small, character-driven story that would have otherwise gone unnoticed or unwanted by Hollywood, and create something that has the tone, atmosphere, and audience-draw of genre films.

Find that wonderful and intriguing concept and then be sure to finish the job by throwing compelling characters and emotional stories into them to create the perfect hybrid that captures the attention and grabs the heart of audiences.

Read the full Scott Beck and Bryan Woods IndieWire piece HERE.

Remember that the spec script is alive and well — and use that knowledge to keep those positive juices flowing. Don't be afraid to be original, unique, and weird with the scripts you choose to write. Don't forget that no matter how much rejection you receive, you can still succeed at the right time, right place, with the right person.

When you're trying to write an engaging page-turner, show the reader how high the stakes are in your script as early as possible. It'll keep them reading. Embrace the "show, don't tell" mantra because it will save you from really bad exposition scenes and keep things more real and organic. Tell stories within small windows of your character's life in order to keep things interesting. And remember that concepts are great, but they're empty if you don't fill them with personal stories and characters that audiences can relate to.

CLICK HERE to read the unique and original 68-page script for A Quiet Place!

Writing your own horror script? Don't forget about the ScreenCraft Horror Screenplay Contest!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter and Facebook!

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!