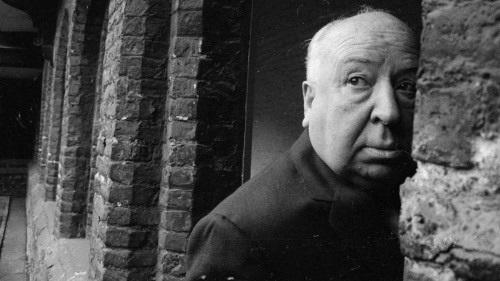

Here’s screenwriting wisdom from the master of suspense himself, Alfred Hitchcock.

We're featuring some of Hitch's most celebrated quotes on directing, writing, and cinematic storytelling as a whole — followed by our own elaboration as to how screenwriters can apply them to their own writing.

Have a suspenseful script of your own? Enter the ScreenCraft Action/Thriller Screenplay Contest here.

"Always make the audience suffer as much as possible."

When we go to the movies, we invest in the protagonist and their situation. We walk into the shadows with them. We ride that rollercoaster with them. We experience every up, down, scare, heartbreak, triumph, and conflict. That's the thrill of watching any movie of any genre.

As you develop your script, you always need to remember that audiences — which includes script readers — want to be taken on that ride. And what thrilling ride doesn't offer twists, turns, steep drops, and anticipation?

Hitchcock's reference to suffering can be perceived as the need for continual and evolving conflict. You, the screenwriter, need to create that conflict every few pages. And that conflict has to grow, multiply, and evolve throughout the story you're trying to tell.

When you make the protagonist suffer, you make the audience suffer along with them. And that is what you want and need to tell a compelling story, no matter what the genre.

"What is drama but life with the dull bits cut out."

Screenplays are just that — drama with the dull bits cut out. Too many screenplays from novice screenwriters forget to cut those lackluster moments out of their scripts.

Those dull bits can be simple things like characters entering and exiting rooms, traveling to and from locations, or engaging in witty banter that has nothing to do with the conflict and the drama of the central story.

Or they can be bigger things like secondary characters and storylines that aren't central to the drama and conflict of the main story.

Cut all of those dull bits out, and the drama and conflict within your story will seem all the more enhanced.

"There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it."

The best screenplays and movies use anticipation as a tool in suspense, horror, and thriller stories. The old adage of "keeping audiences on the edge of their seats" refers specifically to anticipation. The bangs of cinema — explosions, scares, visuals — make them jump out of their seats. But the expectation of those bangs is where you genuinely capture and engage the audience.

The adrenaline gets flowing as we anticipate what is going to happen. And that anticipation can be specific to the whole script building to the end or during particular scenes, sequences, and moments throughout — preferably a compilation of all.

So when you're crafting scenes of suspense, horror, and thrills, use anticipation a majority of the time through those sequences and scenes. Build, build, and build until it's time to unleash that bang.

"The length of a film should be directly related to the endurance of the human bladder."

While this is a clever quip from the master of suspense, there is a screenwriting lesson to be learned.

The length of your screenplay does matter. A 150-page screenplay is overwritten, plain and simple. Yes, you read about this auteur or that auteur that has written a screenplay as long as that, but many of those pages are never shot — or they go into detail within the scene description with camera directions and other elements that should not be included in your spec scripts.

If your screenplays are consistently ending up at 120 to 130 pages or more, it's overwritten. Some elements need to be whittled down, whether it be B storylines not central to the A story, repetitive scenes, overly long scenes, long scene description paragraph blocks, or overwritten dialogue that goes on forever.

Try to get that script somewhere within the sweet spot of 90 to 115 pages. Yes, there are exceptions, but when you go in with a specific page count goal, it helps you to avoid writing those elongated scenes, sequences, and scene descriptions.

"Dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms."

The adage of "show, don't tell" can point directly to dialogue (or lack thereof). The important part of any cinematic story is what audiences see. The actions and reactions of a character tell so much more than any dialogue.

Dialogue certainly has its purpose, but the visual depiction of a character is even more critical to the success of any screenplay.

Too many screenwriters rely on the dialogue to tell the story. Some script readers can merely follow the whole story by skimming through the dialogue only, without missing a single story beat or moment. That's a poorly written screenplay. That's a screenwriter using dialogue as a crutch.

Show, don't tell. When you're writing your screenplays, find ways to use the eyes to tell the story. Visualize what a director would focus on in that respect and try your best to interpret that within your scene description through action, reactions, and silence accompanied by emotion.

"Give them pleasure — the same pleasure they have when they wake up from a nightmare."

When you have a nightmare, you wake up in a sweat because of the cathartic impact that it had on you. It wasn't a subtle scare. It wasn't forgettable. It was cathartic. It had enough effect on you that it shook you out of your deep sleep.

That is what you want to do with your screenplays. You can't leave audiences or that reader with subtle moments. You have to shake them out of their seats.

Go big or go home. And that should apply to the opening of your screenplay, the turning point that leads the character in their journey, the twists and turns that you reveal, and the impactful ending — and then everything in between.

"The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture."

This takes us back to conflict. When the villain is successful, the protagonist is undergoing seemingly endless conflict. And when you have an ongoing conflict that builds, multiplies, and evolves, you're telling a successful cinematic story.

"In films, murders are always very clean. I show how difficult it is and what a messy thing it is to kill a man."

Audiences are like every human being — curious. There is a voyeuristic nature to us that compels and intrigues our minds. Hitchcock often tapped into that human nature. Instead of having Norman kill Marion Crane with one stab to the back in the shower, we see the knife go down over and over and over onto her body.

It's a messy thing to kill a human being. Sure, you could show that one gunshot, that one stab, or that one crash. But it's all the more enthralling and engaging to inject some more conflict and reality to those situations within your script.

Audiences love to be shocked. It's not about glorifying violence. It's about showcasing the horrors of violence — the real horrors of it.

"Luck is everything. My good luck in life was to be a really frightened person. I'm fortunate to be a coward, to have a low threshold of fear, because a hero couldn't make a good suspense film."

Fear is the most significant generator of compelling concepts to explore in your screenwriting.

Fear of the water. (Jaws)

Fear of spiders. (Arachnophobia)

Fear of clowns. (It)

Fear of enclosed spaces. (Buried)

Fear of speaking in public. (The King's Speech)

Exploring your fears — or the fears of others — can lead to so many outstanding concepts to develop in any genre.

"A good film is when the price of the dinner, the theatre admission, and the babysitter were worth it."

If you want to stand out, you have to metaphorically make the price of the dinner, ticket, and babysitter worth it for the reader and eventual audience.

Telling your version of what's already been in theaters isn't going to be worth all of that — we've been there already.

Writing a small, quirky comedy or drama isn't going to be worth all of that either, even if there may be a place for those stories somewhere.

When you're a screenwriter trying to break through those Hollywood walls amidst tens of thousands of others trying to do the same thing, you have to give that reader, that manager, that executive, or that producer something that makes them feel like your script was worth the time spent on reading it — and then some.

"If it's a good movie, the sound could go off and the audience would still have a perfectly clear idea of what was going on."

In screenwriting context, if it's a good script, you could not read any of the dialogue and the reader would still have a perfectly clear idea of what is going on.

Visuals drive this visual medium. Find any way you can to tell a story through visuals, rather than the dialogue.

"The only way to get rid of my fears is to make films about them."

Screenwriting and filmmaking are fantastic forms of therapy. When you're writing about your own fears, your own feelings, and your own stories, you are processing those personal elements through a different lens — figuratively and literally speaking, depending on if you're a screenwriter writing or a filmmaker filming.

"Write what you know" is less about where you are or have been physically in life or in your career and more about what you know through your fears, your strengths, your weaknesses, your wants, and your needs.

When you process those things through your writing or filmmaking, you can often come to terms with what you fear, what makes you sad, what makes you mad, and what can eventually make you happy.

It's good therapy.

"I am to provide the public with beneficial shocks."

If there was ever a straight to the point job description of the screenwriter — especially one that writes within the suspense, horror, and thriller genres — that is it. That is what you are on this Earth to do.

Not cheap shocks. Not subtle shocks. Beneficial shocks that give the audience what they came to the theaters for in the first place — to be entertained and moved in some way that is memorable.

You make them laugh when they need to laugh, cry when they need to cry, cheer when they need to cheer and scream when they need to scream. And yes, everyone needs a good scream now and then. Just ask the Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock — he lived to accomplish that because he knew that's what audiences wanted deep down.

Read ScreenCraft's Screenwriting Wisdom from Steven Spielberg!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!