Screenwriting Wisdom from Stanley Kubrick

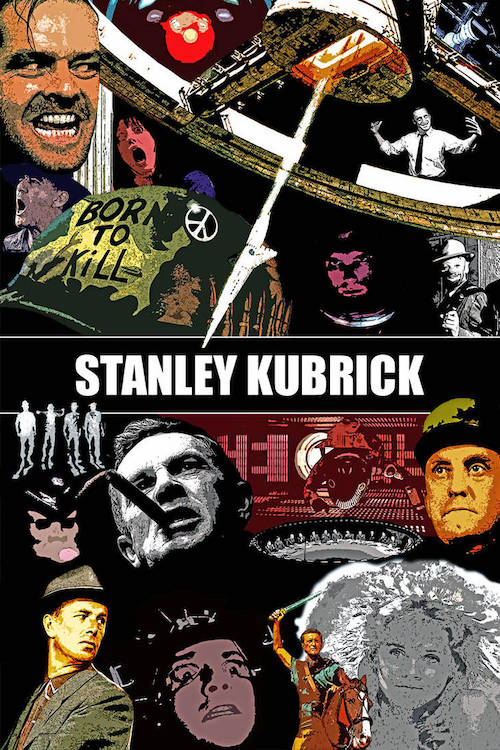

What screenwriting lessons can we draw from the words of one of our generation’s most celebrated directors — Stanley Kubrick?

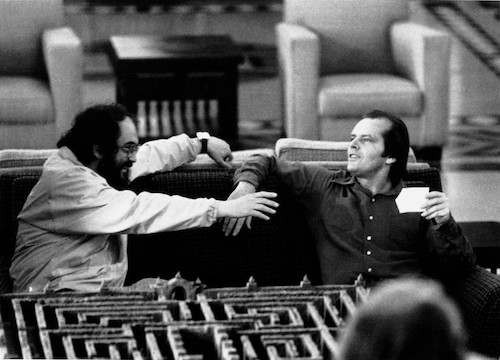

Film is a collaborative medium. Everyone from the crew to the director is a storyteller. The screenwriter and screenplay are just the beginning. Some directors are masters of their craft, while others encompass the whole spectrum of cinematic storytelling with passion and vision. Stanley Kubrick is one of those visionaries that transcends his position as a mere director.

He is both a screenwriter and director, having adapted books and short stories for all of the films he has directed.

Before his death in 1999, Kubrick directed a number of acclaimed films, including Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove (1964), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

He was Oscar-nominated four times for Best Director and five times for Best Screenplay — shockingly never winning in either category.

Read More: The 20 Best Directors of All Time!

Here we feature some of Stanley Kubrick’s most celebrated quotes on directing, writing, and cinematic storytelling as a whole — followed by our own elaboration.

"A film is — or should be — more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods and feelings. The theme, what's behind the emotion, the meaning, all that comes later."

If you've watched interviews with Kubrick — the few that there are — you'll often hear him say that theme comes after the fact. And that writers shouldn't go in with a plan to center every given scene and moment around a chosen theme. Instead, the writer should focus on the moment and emotion that the scene calls for, depending upon the character and the conflict they are facing.

Theme is a vital element for screenplays, but screenwriters need to remember that it's often subjective — interpreted through the lens of each individual audience member and what baggage, beliefs, and perspective they bring into the theater.

Theme will show itself organically. Don't make the mistake of overindulging in it through your scenes and moments within your script.

"You sit at the board and suddenly your heart leaps. Your hand trembles to pick up the piece and move it. But what chess teaches you is that you must sit there calmly and think about whether it's really a good idea and whether there are other better ideas."

He often attributes the lessons of playing chess to the lessons of writing. This quote is a perfect analogy to the experience of writing a novel or screenplay.

You sit down in front of the screen, nervous at first. As you begin to write scenes and moments, you're making decisions on the story. And while doing so you must sit calmly and decide whether your "moves" are good ideas and whether or not there are better options.

That's writing.

"The screen is a magic medium. It has such power that it can retain interest as it conveys emotions and moods that no other art form can hope to tackle."

Writing for the screen is very different than writing for the stage or literary platform. It's a visual medium, tasking the screenwriter with the challenge of telling a story and portraying characters, not through inner feelings and inner dialogue — as is often the case with novels — but through visuals and what can be seen and heard on the screen within the confines of a two-hour (give or take) window.

And unlike theater, which is dialogue and performance driven, film captures emotions and moods in so many different ways through different scopes and visuals.

Learn how to write great movie dialogue with this free guide.

"A filmmaker has almost the same freedom as a novelist has when he buys himself some paper."

We've now reached an era in filmmaking where anything is possible. This fact should be a breath of fresh air for screenwriters. You can write anything — and anything visual is possible.

"Among a great many other things that chess teaches you is to control the initial excitement you feel when you see something that looks good. It trains you to think before grabbing and to think just as objectively when you're in trouble."

Continuing with Kubrick's chess analogies, this lesson points to how important it is to choose your projects wisely. Something may seem like a great idea at first glance, but you always have to think before you commit. You need to see if anyone else has made such a project, or research to see if anything similar to your idea is in the works at studios and production companies.

And then you need to explore the worth of the concept and what it has to offer. Where can you go with it? Is it just an interesting gimmick, rather than a full-fledged story?

Take your time when you're choosing each project you take on.

"It's crazy how you can get yourself in a mess sometimes and not even be able to think about it with any sense and yet not be able to think about anything else."

Most writers can relate to this. When you're struggling with a scene or character, it scrambles your mind to the point where you can't think straight. What you believe to be good solutions turn out to be horrible. And the more you think about it, the worse it gets. The more you tinker with it, the deeper the hole you find yourself in.

That's writing. That is your brain — and more specifically your imagination — hard at work.

But don't worry. You'll figure it out.

"Perhaps it sounds ridiculous, but the best thing that young filmmakers should do is to get hold of a camera and some film and make a movie of any kind at all."

If you're a filmmaker, studying the trade can only take you so far. The best education you'll ever have is actually doing it.

The same can be said for screenwriters. You can study story and structure theory all you want, but until you actually sit down and write, you won't be learning anything.

The theoretical study of film and screenwriting have little to do with the actual process of crafting a story — most of which is instinctual.

"If you really want to communicate something, even if it’s just an emotion or an attitude, let alone an idea, the least effective and least enjoyable way is directly. It only goes in about an inch. But if you can get people to the point where they have to think a moment what it is you’re getting at, and then discover it, the thrill of discovery goes right through the heart."

Kubrick offers a brilliant quote that screenwriters can apply to their handling of scenes and moments within their screenplays. The least effective way to make a cathartic impact on the audience is by having the characters handle whatever conflict they are facing directly.

The indirect approach is often the most impactful. In real life, we don't scream at the other person and tell them how angry we are with them. We avoid confrontation whenever we can. We go off into another room and scream. We take out our anger and frustration on others.

That's the indirect approach. And it's far more interesting for the audience to watch because it builds anticipation for the moment where the characters are finally forced to face their conflict directly.

"I have always enjoyed dealing with a slightly surrealistic situation and presenting it in a realistic manner. I've always liked fairy tales and myths and magical stories."

Some of the greatest cinematic tales have followed this lead.

E.T. is a fantastical and surreal story about an alien being and the powers it has. But Spielberg embedded that fantasy into the realistic setting of a boy dealing with the divorce of his parents.

Read ScreenCraft's Screenwriting Wisdom from Steven Spielberg!

Kubrick accomplished this brilliantly within his classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. He took the then surreal notion of space travel and future technology and placed it within a realistic setting, as opposed to the science fiction and science fantasy stories that came before it. He raised the question of, "What if Artifical Intelligence turned on its human masters?"

Fairy tales, myth, and magical stories are even more intriguing when they are told on the landscape of reality.

"It almost never is a question of, 'What does this scene mean?'... if the thing is truthful, and you don't feel anything about it that's false, and if it's interesting, and if it still feels like what you were feeling, I find it's a much more intuitive process. More like what I would imagine writing music is like."

While some people like to over-analyze the process, pick their theme and knowingly inject it into every possible element of every moment within the script, most writing is intuitive. And screenwriters need to remember and embrace that.

If you spend too much time worrying about what the scene means and what themes lie behind the character, story, and moment, you're not being as truthful as you should be. Instead, you're trying to attain an objective — plotting towards a goal — instead of just offering a truthful and cathartic moment as your characters deal with their emotions, inner conflicts, and outer conflicts.

Trust your instincts and let the intuitive process take hold. You're doing your screenplay right as long as everything feels interesting and truthful to the characters and situations you conjure.

"I've never achieved spectacular success with a film. My reputation has grown slowly. I suppose you could say that I'm a successful filmmaker-in that a number of people speak well of me. But none of my films have received unanimously positive reviews, and none have done blockbuster business."

by DrDyson

It's tough to believe that Stanley Kubrick has never won a Best Director or Best Screenplay Oscar. It's even more difficult to fathom that most of his films didn't make huge box office numbers and critics were often split down the middle.

In hindsight, most remember him as one of the greatest cinematic storytellers of all time.

Read ScreenCraft's Screenwriting Wisdom from Martin Scorsese!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!