What is it like when a screenwriter signs with a manager?

Screenwriting articles, blogs, books, and seminars always offer directives, dos, don'ts, and various methods on how to find representation. While the information is helpful — and applicable — sometimes it's easier to learn from first-hand accounts and the triumphs and tribulations that were experienced.

I'm going to break the fourth wall and speak directly to you screenwriters out there in hopes of sharing my story, and the lessons learned so you can have a peek into the life of a screenwriter who has signed with a manager — resulting in major studio meetings, studio contracts, and produced screenplays.

Screenwriter in Training

I moved to the Los Angeles area in 1999 from "Cheeseland" Wisconsin to pursue a dream career in screenwriting and the film industry as a whole. While my wife attended graduate school, I signed up for movie extra jobs. While I had minor and misguided acting aspirations thanks to the story of Good Will Hunting writers and stars Ben Affleck and Matt Damon, I quickly realized that I didn't have an acting bone in my body. But I still wanted to be on movie sets to learn the ins and outs of production, so I kept with it.

I worked on a lackluster television miniseries about the Beach Boys, where the boyfriend of a fellow movie extra became overly jealous after I was chosen to sit with her in a classic 1950s car for a featured crane shot.

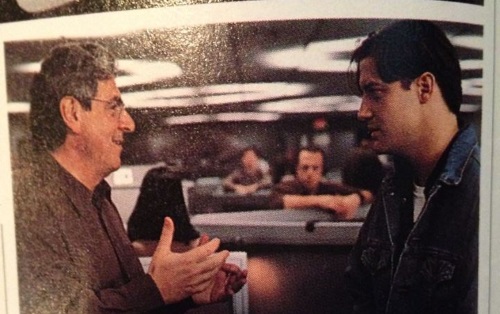

I worked on the charming but underwhelming remake of Bedazzled, starring Brendan Fraser, where I met a Ghostbuster — writer/director Harold Ramis. Between shots he came up to me and introduced himself, leading to a pleasant conversation. I left a thank you note meant for him with the AD (Assistant Director) and was later called back for two more weeks of work.

That's me next to the woman in the center.

That's me photobombing in the center between the late Harold Ramis and Brendan Fraser in a picture that debuted in Premiere magazine.

I worked on the Oscar-winning Traffic as both a stand-in and movie extra where I found myself assigned to a San Diego hotel penthouse, locked in the room for ten hours watching Benicio Del Toro's Oscar-winning performance, as well as Steven Soderbergh's Oscar-winning direction. I then went poolside as an extra for the now classic scene of Del Toro's character monologue in the water.

See those two guys? No, not the ones the camera is focusing on — the two walking near the pool on the left. That's me far left.

As years went by, I was working hard on my screenwriting. I wrote some genuinely terrible screenplays but learned from my own mistakes. As I honed my craft, we relocated to Culver City across the street from Sony Studios — the old MGM lot of Hollywood lore where all of the old westerns were shot, as well as my favorite show The Twilight Zone and endless feature classics like The Wizard of Oz.

After months of trying to get a job on the lot, I walked up to a security guard and asked, "How do I get a job here?" Two weeks later I had an all-access pass to a major movie studio lot.

I quickly worked my way into an office position, which led to a studio liaison job working directly with all incoming film and TV productions, as well as incoming studio executives. I parlayed that latter access to a studio script reader and story analyst position — my dream job at the time. It was then that I attained my true screenwriting education, reading hundreds of screenplays ranging from seasoned professionals to lowly newbies like I was. This allowed me to advance my screenwriting to the point where my work was actually worth reading.

Time to Get Creative

I left the full-time position at Sony when our first son was born. My wife insisted I stay home with him and focus on my writing full-time. Needless to say, I didn't hesitate.

I worked on what would become my then marquee screenplay, Doomsday Order, which told the story of a submarine crew ordered to launch their nuclear arsenal at the brink of World War III and must relocate to a deserted island where they degenerate into mutiny and savagery amidst the struggle to survive — Crimson Tide meets Lord of the Flies.

When it was finished, I took it to all of the industry contacts I had made during my Sony days. I was sure that with the connections I was blessed with (I played basketball with Adam Sandler for crying out loud), the high concept script would surely land me at least a paid option or studio writing assignment.

Um, no.

While the script was well-received, no one was biting. I had exhausted each and every one of my contacts.

So it was time to get creative. I went back to a Wisconsin-based screenwriting teacher that taught my first and only screenwriting course. She suggested that I contact the group of University of Wisconsin alumni that were working within the industry. I wasn't an alumnus myself, having only taken one screenwriting course through their extended education program, but my wife was so I decided that there was nothing to lose. The worse they could say was no.

I drafted a simple query email and went through the list of alumni, searching specifically for those working in development on any level. I ear-marked a dozen of them and sent out my queries, which included the logline for Doomsday Order.

Nothing. No response. The script even made the Top 30 of Scriptapalooza to my utter delight — but it led nowhere.

And then one day, a month or so later, one of the alumni that I queried responded. He was a junior executive at Paramount and requested a PDF of my script. This was it! This was the moment I had been waiting for. They'd read it, love it, and buy it.

Um, no.

Silence. Two long months of silence. Until one night I came home to find a voicemail on my now ancient Nokia cell phone.

"Hey, Ken. This is John Doe (not his real name obviously). I'm a literary manager, and my friend at Paramount told me that he requested your script and put it through the Paramount system. It tracked amazingly. He usually contacts me when a hot writer or script comes up. I'd love to sit down with you and discuss representation."

It's the dream call or email that every screenwriter wants to get. By this time, I was a little seasoned in the inescapable deadends, scams, and "too good to be true opportunities." So while I was intrigued, I was even more skeptical.

The Meeting

The cliche coffee shop meeting in the cliche setting of Burbank.

I arrived fifteen minutes early, dressed in business casual. Most screenwriters would be nervous, excited, or both. I was ready to accept the fact that he was going to ask me for upfront money to be my manager, so my state of mind was more along the line of preparing for war.

I would simply listen to his pitch, wait for his upfront price to be divulged, and then shake his hand extra hard while saying, "I appreciate the time, but real managers don't ask for money."

He was early too, which led to that unavoidable and awkward moment of staring at each other wondering if we were the ones we were waiting for. He made the first move, and we sat down.

Pleasantries and small talk were exchanged while my inside dialogue to myself was saying, "Just give me the schpeel so I can put you in your place and go get some In-N-Out burgers and fries to wallow in self pity."

"Don't worry. I'm not going to ask you for any money." That was the first thing he said after a brief pause post-small talk.

Now my state of mind was a mixture of utter relief and utter glee. But was he for real?

We talked about the script. He was in love with it, which was perhaps the best part. Hearing validation is something that every screenwriter strives for. It fuels you. It makes you feel the relief of knowing that you haven't just wasted months of your time writing this script.

After a long conversation, we shook hands, and he told me that he'd email a contract for me to sign shortly. When it arrived, I read it with that same apprehension, only to feel that same relief and glee after seeing that the contract stipulated no upfront payments, no ridiculous 50/50 script sale share (10% commision only, as it should be), and no surprise scam clauses.

Now it was time to rewrite the script before he took it out wide for all of Hollywood to read.

The Rewrite

Make no mistake, when you sign with a manager (or agent), there's likely going to be some additional work done on the script. In fact, you can expect at least one or two more drafts before it's taken out anywhere.

It's about catering the script to the needs and wants of the industry contacts the manager will be taking the script out to. These drafts may entail simple touch-up work if you already have a superbly strong draft. Others may require additional story and character revising or even the reconceptualization of the first act, second act, third act, or even the whole script.

It will seem odd and ironic that the script they appeared to love apparently needs a lot of work, but that's the business.

Thankfully, my manager (as he now was) only wanted to enhance the third act. We agreed on various updates and three weeks later we had a final draft that we were both excited about.

The Water Bottle Tour of Hollywood

It's a staple tour in the life of any screenwriter. The cost is merely years of anguish to finally write a script worth reading, followed by additional years finding someone that will take it out.

The water bottle tour of Hollywood refers to the multiple meetings that your representation will set up after they've released your script wide throughout Hollywood. Which basically means that the manager has exhausted all of their industry contacts for this script of yours. After that, you wait and see who bites.

With each of the meetings, you'll surely be offered a bottle of water (hence the moniker).

I finally knew throughout my whole heart and soul that my manager was genuinely legit when he set me up with meetings at nearly all of the major studios.

I was now on the guest list at Universal, Dreamworks, Sony, Warner Brothers, and Disney. They loved my script and wanted to meet me.

Each meeting was exhilarating. Even though I had worked at a major studio, it was a thrill to be walking freely through the lots of others. You instantly feel that you've made it, even though you haven't sold a damn thing.

All of the meetings went well. I was speaking with development executives, which was a thrill because they are the ones that offer paid options, acquisitions, and writing assignments.

Strangely, they don't ask you too much about the script that got you in there. Sure, it opens the conversation but what they really want to talk about is you, your writing, and one particular question that each and every one of them asks, "What else do you have?"

Now, there's a reason I always tell screenwriters not to market a screenplay until they have three to five solid efforts worth reading. At the time, because it happened so fast, I didn't have another script to pitch. The ones before Doomsday Order were embarrassingly horrible — written well before the screenwriting education I acquired during my studio script reader and story analyst days.

So when that question came up, I could only point to concepts that I had in development for my follow-up. Some of the development executives responded well to those concepts, but the scripts weren't written yet.

Read ScreenCraft's Are You Truly Prepared for Success as a Screenwriter?

Regardless, I walked out of each and every meeting on cloud nine. Each of these executives gave me their cards and insisted that I stay in contact.

Reality Bites

After each meeting, I'd call my manager exclaiming how wonderful the meetings were and how pleased the executives seemed to be with me.

"Hey, take it easy. All meetings go like that."

Yes, reality bites. It was a lesson I learned the hard way. It felt like these executives were my new best friends. But I never saw any of them again.

No offers were made. No deals were signed. No follow-ups came.

A Secret Revealed

Before I had met my manager, I had a revelation of sorts during a visit home to Wisconsin for the holidays with our newborn son. We had no family in California. Our son's grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were all back in the Midwest two thousand miles away. So being back home with this new little mini-me was amazing.

One cold Christmas Eve night, I heard a voice say, "It's time to come home."

That January I shocked my wife with the reveal that I thought we should move back to Wisconsin to raise our son close to family.

Despite my dream of being in Los Angeles. Despite all that I had accomplished towards that dream.

So before the fateful call from a manager, we had decided to move back home. My wife had looked for and found a job in Wisconsin. We were in full preparation for the move until this manager revelation and everything that came after it happened.

But this was my family. This was my son. And priorities change.

I let my manager know of the move after my initial studio meetings. It wasn't concrete before, but now it was in full swing. He was surprisingly supportive. I didn't need to be in Los Angeles to write, as long as I was available to fly back for meetings.

In 2006, I left Los Angeles. I drove out of the Sony gates (I had been working parttime as a consultant) after my last night on the clock and cried like a baby.

Lightning Strikes Twice

My manager and I developed my next script through emails and phone conversations. We decided on an action drama that I had in my head and had pitched successfully during my studio meetings. People were waiting for it.

The script was One Shot One Kill.

When it was finished, my manager took it out wide, and Lionsgate quickly came in and offered a paid development deal. After a decade of writing, I had finally secured my first paycheck.

But then two things happened. The economy collapsed, and the Writers Guild of America went on strike, changing the whole film and television industry — to this day.

Studios were dropping deals left and right. I was one of them as my contract wasn't renewed and the script was never fully acquired, produced, or released.

After another script or two, my manager and I agreed to go our separate ways. The industry was still in turmoil. Spec script sales were abysmal. Hollywood became obsessed with intellectual property, especially after Marvel hit it big with Iron Man, leading to multiple connected franchises based off of comic book characters.

A couple of years went by and I was representing myself. A chance connection with a Hollywood producer that was from Wisconsin led to a phone call. I pitched him some of my scripts and he wanted to check them out. There was a catch though. He needed a manager or agent to hand them over to him. It's a staple request for many established producers. It legitimizes the transaction. So I contacted my former manager and he didn't hesitate to send the scripts over to this producer for me.

The producer loved my work and hired me for my first paid writing assignment, which was already pre-sold in foreign territories based on the concept alone. This thing was going to be produced. And it was. Not well, but it had a name cast, and screenwriter-boy got paid.

Despite not doing anything besides handing over those scripts to the producer to offer some validation on my end, my now former manager was given 10% commision of what I made on that job. But he deserved it because I wouldn't have been where I was — or where I am today — without that effort and the efforts beforehand.

Lessons Learned from How I Met My Manager

If you've been paying attention and haven't fallen asleep yet, you've hopefully picked up on the many lessons you hear or read about in screenwriting blogs, articles, books, and seminars — including those written by yours truly.

It's not BS. It's not rhetoric. It's not just words written for content. It's advice, knowledge, and information attained through decades of figurative (and sometimes literal) blood, sweat, and tears.

- It really does help to move to Los Angeles. That's where the magic is happening, the deals are being made, and where the meetings are.

- Do everything you can to get into the industry to make contacts and garner experience, even if it means working as a lowly movie extra or security guard.

- And as you do so, keep writing. And as you keep writing, know that those first couple of scripts are going to be your worst.

- When you sign with a manager, the script isn't even close to being done. You will be asked to rewrite, rewrite, and rewrite. It sucks, but you have to embrace the suck and get through it.

- Don't market any screenplay until you have at least three to five solid efforts worth reading and considering because the first question they always ask is, "What else do you have?" And that's really what those meetings are about.

- Keep yourself grounded when you get your validation because validation does not equal paid gigs. It's just validation — another step up the ladder.

- Beware the "friendships" you make with Hollywood insiders. They're not your friends 99% of the time. They're just hustling like you are.

- Stay grounded. It's okay to be excited about signing with a manager and meeting with industry insiders. Celebrate over the weekend but then realize that there are no promises or guarantees in Hollywood. You have to keep writing and grinding away.

- There's always another script. It's NEVER about that one. You get better with each screenplay you write.

- And yes, while it's nice to live in Los Angeles, often necessary to be on call for meetings, and magical to be where the action is, you don't always have to live in La La Land to sell a script or nab that paid writing assignment. All of my paid gigs have come after moving two thousand miles away from Hollywood. Thus, anything is possible. But it's damn easier being there, that's for sure.

Keep writing. Keep dreaming. Hopefully, you've learned a little bit from my point of view as I've told you the story of how I met my manager. And know that it's just one of many. You can meet them through contest placements and wins, through film festivals and conferences, through creative networking, or through streaks of luck as you find yourself at the right place, at the right time, with the right people.

Just know and understand that the journey doesn't end when you sign with them. It's just a new beginning.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!