This article contains major spoilers for the films Paper Towns and Me And Earl And The Dying Girl. You have been warned.

The Manic Pixie Dream Girl is a character trope that many are sick of encountering, including the man who coined the term. In his original article for A.V. Club, Nathan Rabin described the type as a “bubbly, shallow, cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” And while they might object to the characterization given the now-loaded nature of the moniker, variations of the archetypal Manic Pixie Dream Girl have been played--often iconically--by actresses as diverse as Zooey Deschanel, Kirsten Dunst, Kate Winslet, Zoe Kazan, Natalie Portman, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, and Keira Knightley. Considering all the amazing female roles that have popped up in films in the last year (Mad Max, Trainwreck, Jurassic World… disagree all you want, I love Claire) you would think the archetype would have burned out by now, and yet this summer two new teen movies employ the character with a twist.

Paper Towns, written by this year’s ScreenCraft Mentor Scott Neustadter, and Michael H. Weber, is based on the novel by John Green. Green previously stated as he wrote Paper Towns that the novel was intended to “destroy the lie” of these female characters. You would never know this from the film’s trailer:

The trailer gives the appearance of using Cara Delevingne’s flighty goddess as the center of a mystery, which it is, but it is definitely not the purpose of the film. The first act is understandably long, as the writers have a lot of ground to cover to show the impetus for our protagonist, QUENTIN’s obsession with the mysterious MARGO. After Margo disappears, Quentin spends the movie searching for her alongside his two best friends, BEN and RADAR.

The film’s greatest strengths are its main deviations from Green’s novel. In the film, the three friends go on a road trip to find Margo and are joined by Margo’s best friend, Lacey, and Radar’s girlfriend, Angela. In the book, Lacey is there for the journey but Angela is not. This is a huge difference. Outside of the road trip onscreen, Angela’s only purpose appears to be to nag Radar. This is never seen, but comes from Radar’s fears of how Angela will react to any change in their plans.

The Angela we see on the road is awesome. She gives Lacey someone to roll her eyes at or look confused towards, and is a perfectly reasonable human being. Radar’s ridiculous embarrassment of the people in his life is a running joke, but his emotional reveal to Angela gives their relationship weight. It also allows us viewers to compare the lack of real emotional connection between Margo and Quentin against Angela and Radar’s easy closeness.

Another major change from book to screen was the entire third act. As the road trip reaches its destination and discovers nothing (completely altered from the book), Quentin has a meltdown. His friends confront him, pointing out that Margo would not have done the same in return, and that they all joined him because they wanted one last trip with their best friends. When Quentin and Margo are finally reunited, she reiterates this same wisdom she attempted to impart to him in the beginning: life is about the journey, not the end result. Margo understands how others view her, and while her constant disappearing adds to her mythos, she disappears in order to find out who she is outside of others’ perceptions.

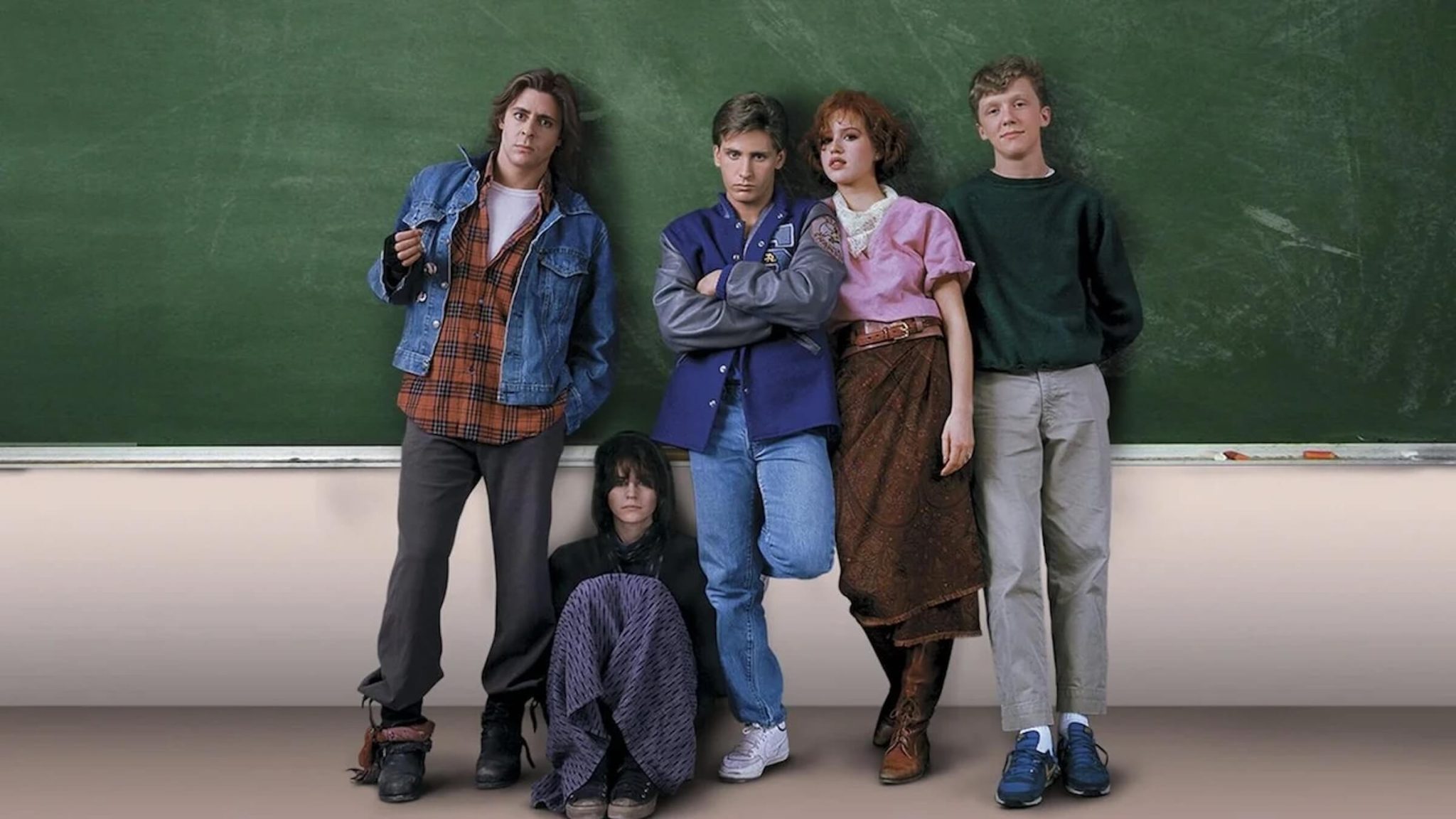

Between the themes that John Green laid out in his story and the alterations Neustadter and Weber made to Angela, the film becomes a John Hughes-esque road trip for the millennial set that tells a beautiful story without short-changing any gender or character.

Similar in bait-and-switch approach, Me And Earl And The Dying Girl gives the appearance of a teen romantic comedy (though it attempts to tell you it’s not), only to eviscerate its protagonist in the end for his actions throughout the film in a bittersweet coming-of-age tale.

Written by Jesse Andrews, the film tells the story of Greg, an average teen who has made it through high school by maintaining polite friendships with everyone while not being part of any one clique. His only friendships are with a history teacher who lets him hang out during lunch, and Earl, with whom he makes parodies of famous films. When his mom tells him his classmate Rachel is dying, he is forced to spend time with her and the two develop a friendship.

The trailer gives the appearance of a rom-com but the film is far from it, completely rooted as a coming-of-age tale, and this is exactly the point of the whole story. Rachel is sweet, interesting, and shares Greg’s oddball sense of humor. She challenges Greg’s anonymous lifestyle, and pushes him to think about his career.

The film moves easily and is entertaining but somewhere in the second half a realization occurs: We know nothing about Rachel from Rachel. Greg doesn’t ask her anything personal. He has spent so much time observing the various groups in school that he assumes he knows Rachel as well as he does everyone else. Any other information comes from stories told in the interviews of the film Greg tries to make for Rachel.

The realization that we knew nothing of Rachel outside of her illness made this viewer irate. They said that this was not a “love story,” but it felt like one. Were we not supposed to be rooting for these two to beat the odds, defy cancer, and live happily ever after? How are we supposed to do that without knowing anything about her? I gritted my teeth and attempted to enjoy what was left of the film without overanalyzing it (clearly not an easy feat).

Then something unexpected happened. The ending we were anticipating began, only to end in the most heartbreaking way possible, allowing the movie to unfold into its ultimate message: Greg never knew Rachel at all, just like the audience, and now he never will. That is the entire point. It is sad to learn, and yet the film does not feel sad, it feels hopeful. Greg has finally learned that life is meant to be lived, and now he will never allow another moment to simply pass him by again.

There are many articles talking about this new “lazy generation” of millennials, but these two movies have touched on the core of the new middle class of teens and twenty somethings. What Scott Neustadter, Michael H. Weber, John Green, and Jesse Andrews know is that this new generation wants to enjoy the journey and not waste time. Many other movies have taught this lesson by employing the vapid MPDG but this tactic is no longer fresh and will not ring true to millennials. These storytellers dug deeper, subverted the trope, and created poignant films that have and will continue to resonate with the intelligent and thoughtful generation it depicts.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!