How to Write and Format a Musical Feature Screenplay

You have a great story, great characters, and know everything there is to know about formatting a feature-length screenplay. But the only problem is — you want to write a musical. How does that change the screenplay's structure and format?

It's one of the most unique questions that screenwriters have, whether it's because they're writing a full out musical for the big screen or if they have scattered musical numbers throughout their script.

If you're aching to write a musical, have musical numbers planned for your feature screenplay, or have moments within your non-musical script that require special format, here is everything that you need to know, complete with full-length feature musical scripts that you can use as examples.

First Ask Yourself: Does it HAVE to be a Musical?

"An original Hollywood musical is an unusual decision for any studio in this day," Lionsgate Motion Pictures Group co-president Erik Feig told Deadline. This was the studio behind the Oscar-winning and box office hit musical La La Land.

Musicals are an uphill battle when it comes to selling them on spec. A majority of musicals that do make it to the big screen are based on pre-existing source material (Les Miserables), are written and directed by auteurs (Damien Chazelle from La La Land), are developed from within studios (especially during the old MGM days), or are animated features (Frozen).

Damien Chazelle stated in the same Deadline article, "There wasn’t a lot of excitement in the room when we initially pitched La La Land around town. Here we are with an original musical, one that incorporates jazz, and a love story where the protagonists may not wind up together; everything was a further death knell. The genre itself, when it’s not based on a pre-existing property, is a scary thing, but the fact that there haven’t been any in a while was part of the appeal."

Feig said that the reason Lionsgate greenlit the musical was because, "... we often make left-of-center decisions. When you look at the success of both companies under one roof, whether it’s a Tyler Perry comedy, The Hunger Games, Twilight... or on the TV side with Orange is the New Black, what’s interesting is that most of what’s worked has been unconventional bets across the board in most genres."

So while selling musicals on spec is a definite long shot, that doesn't mean that it won't happen. Just take a look at your story and make sure that this uphill battle is going to be worth it. Ask yourself, "Could this story work just as strong without the music?"

If the answer to that question is no, then here is what you need to know about writing these types of screenplays.

Know the Two Types of Cinematic Musicals

Cinematic musicals can generally be broken down into two specific types.

All Sung

The perfect example of this type of musical is Les Miserables (click on the title for the feature-length script).

This is where all of the dialogue is communicated through song. There are specific musical numbers within, but even the dialogue in between them is articulated through song delivery.

Integrated

This is the format that most musicals use. La La Land, Frozen, and Beauty and the Beast are examples (click on the titles for the feature-length scripts).

Musical numbers are integrated with spoken dialogue scenes and are often — but not always — part of the overall plot of the film.

So which type of cinematic musical were you conceptualizing?

Understand the Struggles Audiences Have with Musicals

Back in the 1930s and 1940s, musicals dominated the cinemas. While the genre continued strongly through the 1950s and 1960s, musicals slowly began to taper off, with exceptions like Grease and other big screen adaptations of stage musicals.

As cinema entrenched itself into more realistic tones during the 1970s, the musical slowly began to fade away. Audiences began to look down on them. They were more and more viewed as the most unrealistic genre. Audiences began to ask, "Why are random characters starting to sing when moments before, their thoughts and feelings were shared through spoken dialogue."

Most of us know that with musicals you just have to accept the fact that the story and characters will stop to perform a musical number — that's part of the entertainment — but not everyone responds to musicals that way.

So how do musicals win over the majority of the audience, as films like La La Land and Grease did so well?

What Is Your Musical REALLY About?

If you're writing a musical script and you don't know the answer to this question, there's a problem. You likely haven't injected the musical numbers with much substance, forcing the reader to ask, "Why do these musical numbers need to be in this script?"

John Kenrick — in his 2000 piece on How to Write a Musical — wrote, "When Jerome Robbins agreed to direct the original Fiddler On The Roof, he asked the authors a crucial question: 'What is your show about?' They answered that it was about a Russian Jewish milkman and his family, and Robbins told them to think again. He wanted to know what the show was really about at its emotional core — what was the main internal force that would drive the action and touch audiences both intellectually and emotionally? Eventually, the authors realized that the show was really about the importance of family and tradition, and about what happens when a way of life faces extinction. This not only gave them the idea for a magnificent opening number ('Tradition') — it also gave what could have been a very parochial show irresistible universal appeal. This is why the fable of Tevya the Russian-Jewish milkman has moved audiences all over the world."

La La Land was really about sacrificing everything to follow your dreams. That was the core of each of the musical numbers, and that is what drew in so many people to the theaters.

Frozen was a film about being yourself and not being ashamed of it.

Les Miserables was about love and redemption.

These are all themes that pull at the heartstrings of audiences.

When you get to the core of the story and characters, you interweave those themes into every plot point, every character arc, every line of dialogue, and especially every musical number. The musical numbers, in particular, need to be an expression of those themes. They are meant to be a heightened version of the dialogue.

The Structure of Musical Screenplays

Musical scripts are structured just the same as one would write a regular feature screenplay — except there are now the additions of musical numbers.

It is the placement of the musical numbers that is key.

Rouben Mamoulian, the original stage director of Oklahoma and Carousel wisely said, "It's the basic law that the music and dancing must extend the dialogue. If you say the same thing in a song you already have said in the speeches, it's without point... a song must lift the spoken scene to greater heights than it was before, or the song must be cut no matter how beautiful [the melody is]. The song must not merely repeat in musical terms what has already been put across by the dialogue and actions."

You need to find places within your screenplay that call for emotional elevation. Go to your favorite musicals, watch them, and see where those songs are positioned within the structure of the story and character arcs.

It's about finding the perfect balance of when to use musical numbers and when not to use them. You don't want to have too few and risk the notes asking, "Does this need to be a musical?" At the same time, you don't want to have too many and risk the notes saying, "The musical numbers are saturating the script and taking away from the story and characters."

So structure the stories like you would any screenplay, but find those key positions where you will place those musical numbers.

How to Format Musical Numbers into Screenplays

This is the crucial question that most screenwriters looking to write musical numbers into their screenplays ask. And it is a difficult question to answer without contradictions arising.

There are a few different ways to tackle this formatting issue. Each method has its pros and cons. To start, you have to think in the context of how you are writing the script, who you are marketing it to, and how you will be marketing it to them.

Are You Just the Writer?

Most people that have worked on musicals will tell you, "Screenwriters write the screenplay — lyricists and composers write the music."

If you're just a screenwriter that is trying to sell a musical on spec — and you have no desire or experience to compose music or direct — it truly is a more difficult venture.

Are You Partnered with a Lyricist, Composer, and Director?

If so, the pitch of the project will be much easier because you are part of a full package.

Damien Chazelle was partnered with his childhood best friend Justin Hurwitz, who composed the music and wrote the songs for La La Land.

These two types of context will dictate how the musical screenplay should be formatted. The locations, scene descriptions, character names, and dialogue will be written and formatted like any other screenplay. The critical difference is how the musical numbers are displayed.

Because Chazelle was partnered with a composer, a majority of the songs were already pre-recorded for the pitch in the form of temp tracks. Chazelle was already an in-demand director due to his indie hit Whiplash, so the process of sending the music tracks along with the script offered them the opportunity not to have to worry about writing in the lyrics and musical number directions within the format of the screenplay itself.

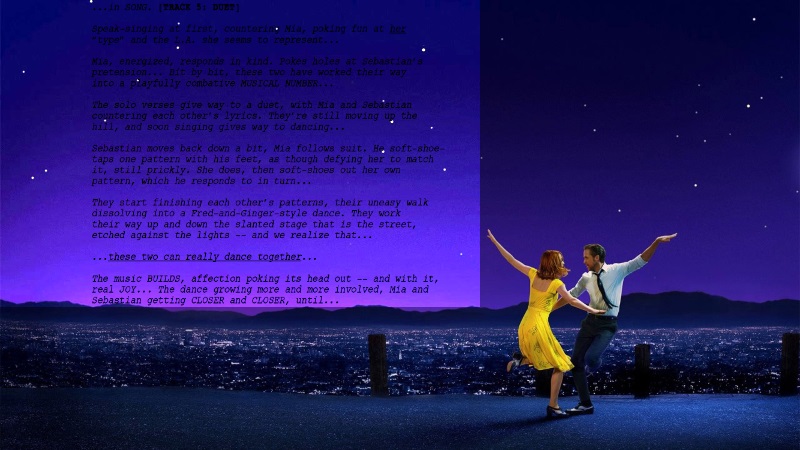

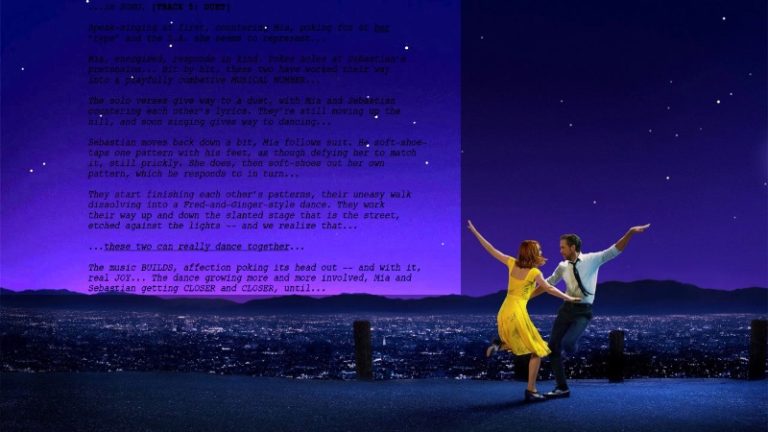

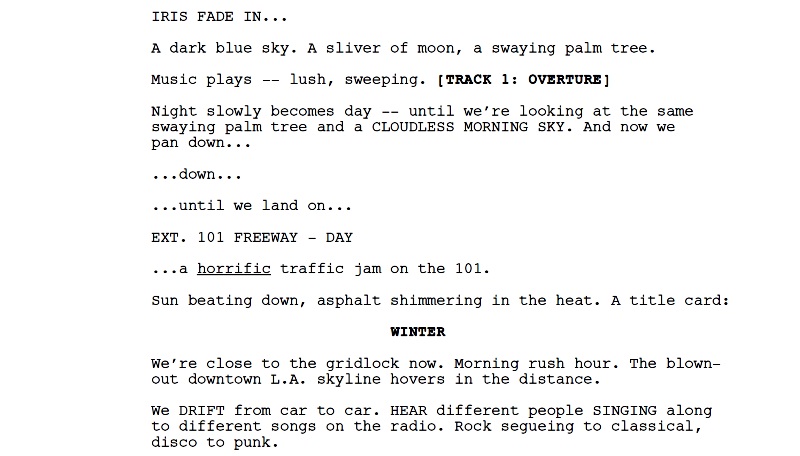

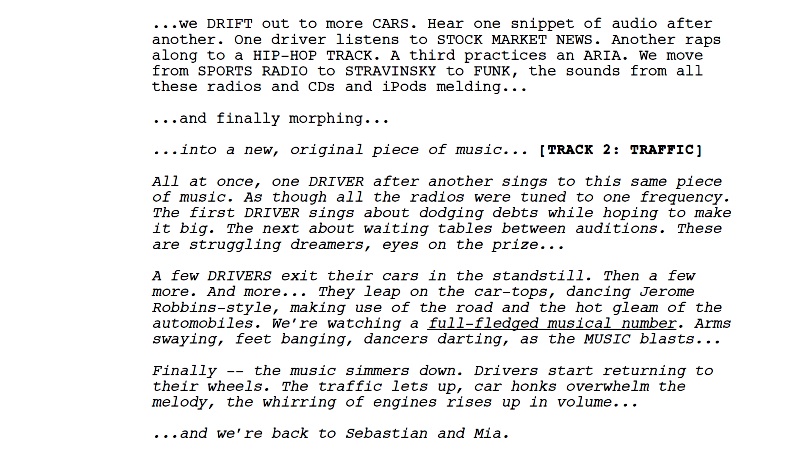

Let's take a look at the first couple of pages from La La Land as an example of how simple this process is.

As you can see, the musical number actions are communicated through simple and non-specific scene direction — but in the case of the musical number actions, the scene descriptions are in italics. This is done to differentiate the musical number and non-musical number scene description.

You'll also notice that there are no song lyrics and singing character names within that sequence. Instead, Chazelle references the songs by particular tracks and track titles. This obviously points to the fact that the people reading the script also had an accompanying CD or digital playlist to reference. This type of formatting is specific to those that will also have the ability to get the pre-recorded music into the hands of the powers that be considering the script.

While those of you writing musical screenplays on spec (speculation that they will sell) can attempt to go the same simple formatting route, remember that it's hard enough to get someone to read your script, let alone have them listen to demo tracks. It's not impossible, but if we're being honest here, it's highly improbable that those you'll be shopping the script to will both read and listen to it.

That is, IF you have the temp tracks to forward. If you don't, you'll have to go to the secondary option of including the lyrics — and character names singing them — within the format of the screenplay.

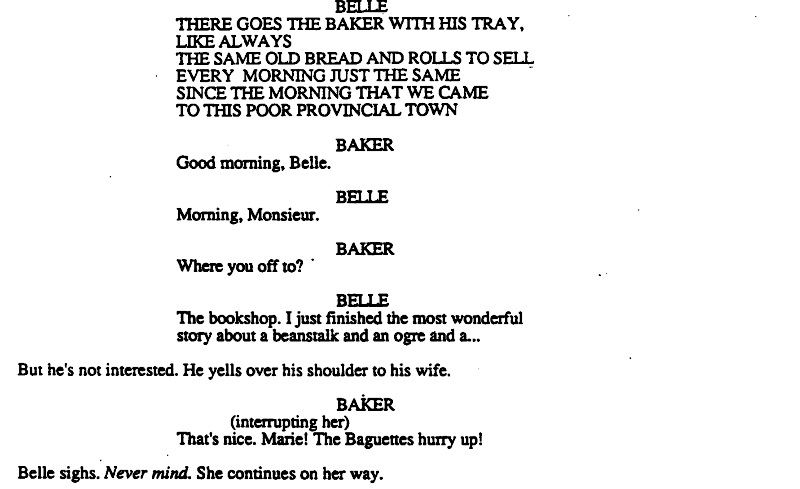

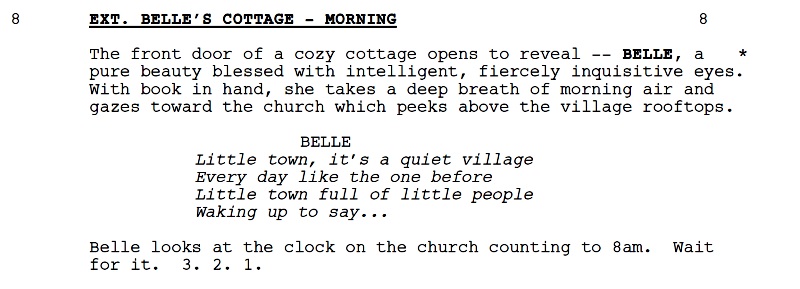

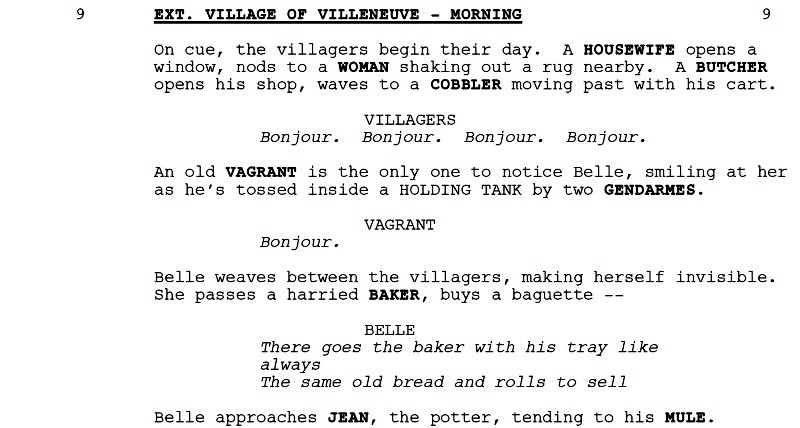

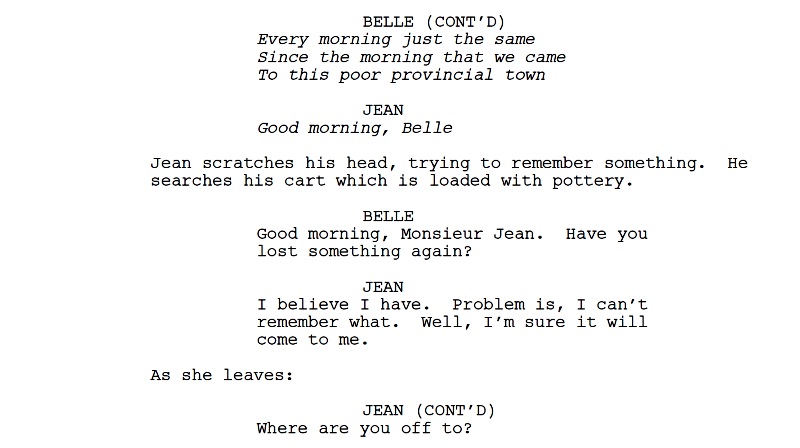

Let's turn to the classic animated film Beauty and the Beast for our first example.

This type of formatting is pretty straight forward as well but allows you to include the lyrics within the screenplay content. The actions of the musical number are written in standard format. In this case, italics are not utilized to differentiate — although keep in mind that this screenplay was written and developed for Disney almost 30 years ago. If you're writing your script on spec, you may want to utilize italics like the La La Land script did, just to offer a smooth read.

With the lyrics, the script initially used parenthesis first to dictate that Belle was (singing). From that point on, the screenplay just has the lyrics in FULL CAPS and written in standard lyric format of having one single line denotes one sung line, as opposed to the lyric lines running together in blocks, separated only by periods, question marks, and exclamation marks, as is the case for standard dialogue.

This type of format allows the reader to experience some of the song. We say some because obviously, the musical composition is the one missing element. That's where this format falters.

The read of a musical script without the music can be a long and arduous experience. That is why it is so challenging to sell musical features on spec.

The sole antidote is to write powerful lyrics that read like poetry. That is when knowing what your story is really about matters most because that will reflect in those lyrics and will offer you the ability to communicate those themes with lyrics that resonate just as much as spoken dialogue would.

When you view the script for the live-action Beauty and the Beast, the format is close to the same, but instead of having the lyrics in ALL CAPS, the screenwriters decided to use italics to denote singing.

The difference between the two is subtle. From a script read perspective, the ALL CAPS option stands out more but can get overbearing to read if a long song is present.

The shooting script for Disney's animated feature Frozen offered an additional option as well.

The writers used both ALL CAPS and BLUE text to convey the song lyric moments.

Between those three examples, there is no clear right or wrong way to present the lyrics. The clear objective is to allow for the best read possible, where the reader can differentiate between spoken dialogue and song lyrics in easy fashion.

Using Your Software to Automatically Format Lyrics

Whatever type of software you are using, there are likely options that allow you to create a new standard software element for writing lyrics within a screenplay. We use Final Draft as the first example here.

You can create a Lyrics element to your specifications:

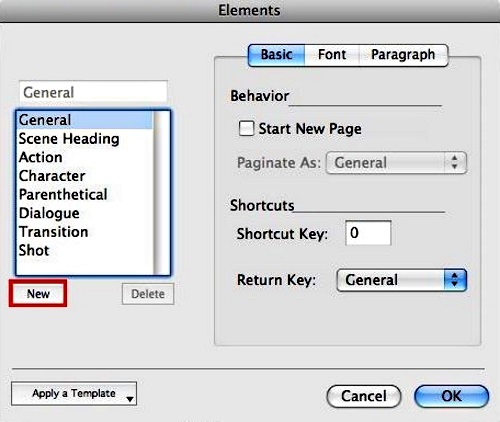

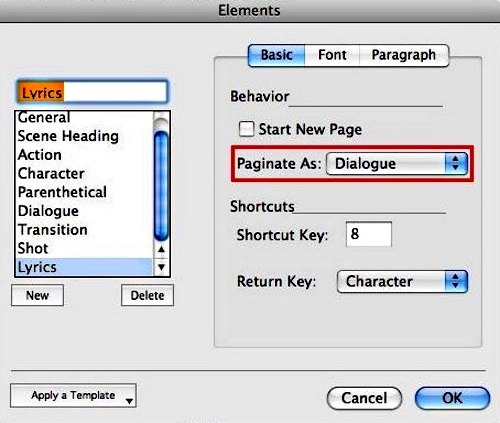

1. Go to Format > Elements;

2. Click New.

3. Call the new element Lyrics (or whatever you like);

4. Go through each tab setting -- Basic, Font, and Paragraph, and customize the new element's look and behavior (in the case of lyrics, you'll want to set them to paginate as dialogue);

5. Click OK.

The element will be added to the list of existing elements in the drop-down menu on the toolbar (FD8 for Mac shown here).

Different versions of Final Draft will vary, but rest assured knowing that most software will have an easy solution once you decide which type of format you'd like to use.

Story First, Music Second

Whichever way you choose to write and format your musical screenplay — remember that story must always come first. Without a compelling story and compelling characters, the screenplay won't have much value, no matter how great the lyrics to the songs are.

The purpose of a musical is not just to use music as a way to tell a story. It's to tell a story a different way by enhancing the emotional story and character moments through song, dance, and musical composition.

When you know what your story is really about — the universal themes — you can write music and lyrics that build upon the action and dialogue of the characters.

Non-Musical Applications

These format options offer you answers to not just writing feature-length musical scripts. They can also be utilized to handle specific musical moments within your non-musical features as well.

If you have a character that is singing in the shower, you can use parenthesis to dictate that they are (singing), and then you can put the lyrics that are meant to be sung in ALL CAPS or italics, depending on your preference.

The same can be done when musical lyrics are featured as being heard onscreen from a radio or other device.

It's Easier Than Most Think

Music in screenplays is a simple formatting process. You always want to keep the general guidelines and expectations of screenplay format in mind, and just use subtle enhancement to convey those musical numbers and moments.

Just remember that the true struggle lies not within how you write those types of scripts and scenes, but why you are writing them in the first place and where you will be attempting to market them.

The musical genre is still somewhat of a niche market. Studios and production companies are still hesitant to make those types of films — unless major talent is already involved.

But know that if you truly feel compelled to write the next possible musical feature — be it live-action or animated, all sung or integrated — it hopefully seems like a less daunting task after you've read this article.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!