How do writers craft protagonists that are engaging, compelling, and interesting? Enter the Antiheroes.

Antiheroes are this generation's go-to protagonist. But why? The answer can be relatively simple — audiences love them because they often dare to say what we all would like to say and do what we all would like to do in any given situation. They are void of the rules and regulations that society has created over the years, whether it's based on law and order or sociological expectations.

They don't have the morals that most in the mass audience have. If they are wronged, they don't go to the law. If they are flawed, they don't try to atone and apologize for it. They are who they are, do as they wish, and take care of themselves in their own unique way.

In turn, cinema is escapism, fantasy, and role-playing at its best. So when we go into that theater, and the lights go down, we can become those characters, if not for just a short period of time. So when we have an antihero as the protagonist, we get to live vicariously through them for a couple of hours and then enter the real world with our morals and ethics intact.

But antiheroes aren't easy to write. Too many writers believe it's a simple formula to follow, thinking that an antihero is just an asshole that happens to be the center of the story — someone that does the exact opposite of what a hero would do.

There are some truths to that approach, but that's just scratching the surface of what it takes to write an antihero that will engage audiences.

So what are the elements that make for a great antihero? How do writers craft these types of characters in such a way that audiences embrace them?

Here we will break down the different types of antiheroes and share the elements of what makes them the antithesis of the standard hero.

Read More: Antihero with a Heart: Analyzing Joel from 'The Last of Us'

Justifiable Antiheroes

When you've decided to tackle an antihero story, character development is key. The best antiheroes often have a reason for being an antihero. It's not enough to simply portray a character that doesn't care about anyone else and has little to no moral or ethical code to speak of — that can lead to writing a one-dimensional character. It can work (see below), but audiences love justifiable antiheroes because they showcase the truth of humanity — that we're all flawed.

Justifiable Antiheroes have a background that shows an audience a cause and effect as to why they are the way they are. This background gives the audience a reason to root for them. Emotions like depression, neglect, grief, and abandonment are understandable. It doesn't excuse someone from doing wrong, but we understand why their world isn't black and white. The best antiheroes travel that gray line in between what most would say is good or bad, justifiable or unjustifiable, right or wrong.

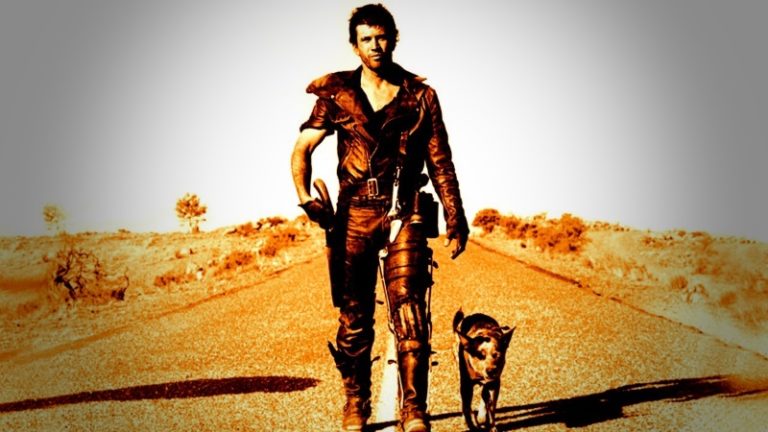

Mad Max

Max Rockatansky from the Mad Max franchise became the loner he is after losing his wife and son to a sadistic biker gang. That carries over to the next film, The Road Warrior, as he is forced to fend for himself. He is deep within the post-apocalyptic wasteland, where every drop of water and gasoline is a luxury. In this type of world, morals and ethics have no place if you want to survive. You either kill or be killed.

Wolverine

Wolverine in the X-Men films was victimized and used as a weapon in his earlier life. He never had a family. Anyone he put his trust into betrayed him. And the society around him as a whole was prejudice against him because of his mutant attributes.

John Rambo

Rambo in First Blood was a Vietnam veteran that returned to a country that turned against him. Every friend he ever had in the military was dead. He suffered from PTSD. He came back to a different country as a different and haunted man.

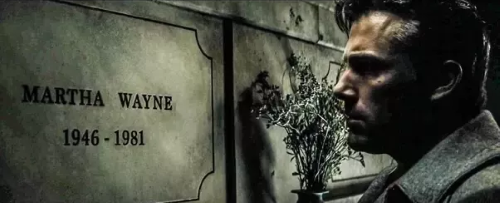

Batman/Bruce Wane

Batman tragically lost his parents as a child. The police never caught his killer. So he dedicated his life to doing what no one could do for him and his family — keep the people of Gotham safe from criminals.

Thelma & Louise

Thelma and Louise were victims of consequences, sparked by an attempted rape. The snowball effect of their actions was arguably justifiable, given the circumstances.

These types of antiheroes give us a reason to root for them. They give us the hope of repentance, atonement, and understanding. And they fit into multiple types of storylines, always offering an added depth of character. They rarely change, but there is enough good in them to excuse the way they do things — just as long as it's for the good in the end.

Near-Hero Antiheroes

These types of antiheroes are the more conventional ones we see in lighter fare — often in animated movies and action adventures. They have nearly all of the characteristics of a hero, but they lack the positive attitude and actions that most conventional heroes have.

To act heroic and take on the mantle of being a hero, they need a push. They need to find someone they actually want to protect or save. They need to solve those inner conflicts that have made them so negative.

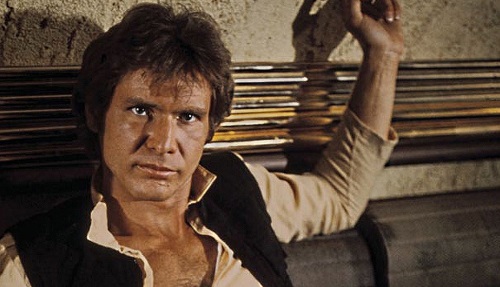

Han Solo

Han Solo was a gambler and smuggler. On the surface, all that he cared about was himself, his Wookie friend, and making money. Throughout the original Star Wars, he pushed up against heroic acts as Luke Skywalker continued to challenge his morals and ethics. But by the end of the film, he became a hero. And that hero status remained throughout the Original Trilogy and into The Force Awakens.

Madmartigan

Madmartigan from Willow had a selfish and cynical outlook on life. He was a disgraced knight and had a vice for beautiful women. But by the end of the film, he was a full-fledged hero that saved the savior of the kingdom, as well as his new friend Willow.

Near-Hero Antiheroes give audiences the satisfaction of seeing a full awakening as they become heroes before our eyes. They make that complete transition from negative to positive and learn the error of their ways.

Sociopathic Antiheroes

These types of antiheroes are those that lack the justification that Justified Antiheroes deserve. They are often criminals, and audiences are not engaged by them due to the hope of seeing their transformation or atonement, but rather out of sheer curiosity. They can certainly showcase a set of morals and ethics, but only through the skewed perspective within their own criminal worlds.

Tony Soprano

Tony Soprano is perhaps the perfect example. He was a loving husband and father, but he often cheated on his wife and even hit his children. He was a loyal friend, but only to a point. If a criminal code was broken, friendship — and even family — didn't matter to him. In the end, he deserved what he got (or didn't get, depending on your Sopranos ending theories). His actions and lack of morals and ethics caught up with him. But audiences loved to peek into the underbelly of America.

Hannibal Lecter

Hannibal Lecter was a charming and educated man that helped Clarice battle her own demons and catch a serial killer. However, he was a violent and sadistic serial killer himself. Again, audiences were attracted to him because of the curiosity of getting behind the mask of a serial killer.

Tony Montana

Tony Montana is an extreme antihero that balances on the line between antihero and villain. Beyond the love for his sister and mother, he has no moral and ethical perspective — even within the context of his criminal world. He does what he wants when he wants. He's a drug addict. He's paranoid. He doesn't trust anyone. And he thinks that money and power should give him the respect he believes he deserves.

Read ScreenCraft's 15 Types of Villains Screenwriters Need to Know!

Sociopathic Antiheroes draw us in by our curiosity. They allow the writer to make no apologies because no justification is needed or granted for a sociopath and their world.

Sure, we sometimes catch ourselves living vicariously through Sociopathic Antiheroes when we watch criminals successfully live the good life after robbing banks or profiting from the underbelly of the country. Look no further than Heat's Neil McCauley for a perfect example of sympathizing with a sociopath. If you watch that film, it's easy to be caught up in the net of big money robbery — to the point where we try to justify what they're doing, even though they kill innocent people and put others in harm's way.

But in the end, we realize that despite the allure of their lifestyle, they are sociopaths when all is said and done.

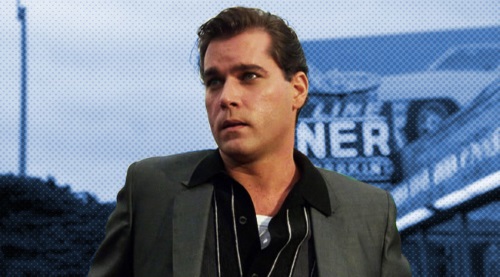

Despite the charm of Goodfellas' Henry Hill, he still robs and murders for a living.

So these types of antihero movies are driven by our deepest curiosities. We certainly (hopefully) don't want to rob and murder, but we are undoubtedly curious about the types of people that do.

Antihero Characteristics

Antiheroes aren't stereotypical role models. They show little to no remorse for their bad behavior and negative outlooks. They often handle situations with their own interests in mind, and they do so without any attention paid to law and order, morals, and ethics.

They can often embody negative characteristics and traits — racism, sexism, call to violence — many of which are inexcusable if not for the good deeds they manage to accomplish within the story. Look no further than the character of Gran Torino's Walt Kowalski for a perfect example.

These — and many more — negative characteristics are excused for three reasons:

- Because they are justified given the background of the character.

- Because they are atoned after learning the error of their ways.

- Because they are set within to develop your antihero further criminal or sociopathic context, thus their actions and reactions are merely a reflection of the world they live in.

But beyond the negatives, the true key to offering the audience an antihero to root for is to pepper those characters with good qualities as well. They can surely have their "save the cat" moments, but it has to go beyond that. We have to see their struggle between choosing between the good and the bad route. That struggle is enough to give us hope that there is good within them — that they just may do the right thing in the end.

Antihero Sides of Morality

Morality and ethics play a crucial part in differentiating heroes and antiheroes.

Jessica Page Morrell, the author of Bullies, Bastards & Bitches: How to Write the Bad Guys of Fiction, offers comparisons between the hero and the antihero, and on which opposing sides of morality they can be found.

- A hero is an idealist.

- An antihero is a realist.

- A hero has a conventional moral code.

- An antihero has a moral code that is quirky and individual.

- A hero is somehow extraordinary.

- An antihero can be ordinary.

- A hero is always proactive and striving.

- An anti-hero can be passive.

- A hero is often decisive.

- An antihero can be indecisive or pushed into action against their will.

- A hero is a modern version of a knight in shining armor.

- An antihero can be a tarnished knight, and sometimes a criminal.

- A hero succeeds at their ultimate goals unless the story is a tragedy.

- An antihero might fail in a tragedy, but in other stories, they might be redeemed by the story’s events, or they might remain largely unchanged, including being immoral.

- A hero is motivated by virtues, morals, a higher calling, pure intentions, and love for a specific person or humanity.

- An antihero can be motivated by a more primitive, lower nature, including greed or lust, through much of the story, but they can sometimes be redeemed and answer a higher calling near the end.

- A hero is motivated to overcome flaws and fears and to reach a higher level. This higher level might be about self-improvement, a deeper spiritual connection, or trying to save humankind from extinction. Their motivation and usually altruistic nature lend courage and creativity to his cause. Often, a hero makes sacrifices in the story for the better of others.

- An antihero, while possibly motivated by love or compassion at times, is most often propelled by self-interest.

- A hero (usually when they are the star of the story in genre fiction, such as Westerns) concludes the story on an upward arc, meaning they've overcome something from within or have learned a valuable lesson in the story.

- An anti-hero can appear in mainstream or genre fiction, and the conclusion will not always find him changed, especially if he’s a character in a series.

- A hero always faces monstrous opposition, which essentially makes them heroic in the first place. As they're standing up to the bad guys and troubles the world hurls at them, they will take tremendous risks and sometimes battle an authority. Their stance is always based on principles.

- An anti-hero also battles authority and sometimes go up against tremendous odds, but not always because of principles. Their motives can be selfish, criminal, or rebellious.

- A hero simply is a "good guy," the type of character the reader was taught to cheer for since childhood.

- An anti-hero can be a "bad guy" in manner and speech. They can cuss, drink to excess, talk down to others, and back up their threats with fists or a gun, yet the reader somehow sympathizes with or genuinely likes them and cheers them on.

These are just general comparisons that you can use to further develop your antihero. Playing with these comparisons allows you to also craft the story around them by forcing the antihero to face conflicts that you conjure, which are inspired by the various sides of morality that antiheroes travel in between.

Moments of Antihero Redemption

Han Solo returned to save the day during the attack on the Death Star. Wolverine always managed to help his newfound family in the X-Men. Mad Max decided to drive the colony's tanker. Rambo spared the lives of those hunting him down and trying to kill him.

The best antiheroes are given moments of redemption in the end.

Even Tony Soprano showed the love for his wife, children, and even spared the lives of friends that did him wrong. Lecter spared Clarice's life. Tony Montana offered money to his mother. While those aren't clear-cut redemption for those sociopaths, we're given little moments that show them walking that gray morality line.

The True Draw of the Antihero

The complexity of these types of characters is an overall better experience for the audience.

Warner Brothers has been struggling to make Superman an engaging character. Why? Because he stands for truth and justice. He's a boy scout. He never does anything wrong. And when they try to portray him as jaded, fans go nuts because that goes against the character's mythos. Yet they've done an amazing job with Batman. Why? Because he's an antihero. He's complex. He doesn't always do the right thing. Justice isn't always true in his eyes. Sometimes justice has consequences — consequences that he's willing to make.

Because antiheroes walk that gray line, we're reminded that the world we live in is not black and white. And we're flawed. Each and every one of us. When we see a character on the screen that emulates that — albeit to enhanced degrees — we take notice and are forced to think about deeper issues. We ask ourselves — and others — difficult questions.

"Han Solo could have left with all of that reward money and lived a fruitful life in a galaxy far, far away. Why did he risk it? What would you have done?"

"Max didn't need to help that colony. He could have driven off and disappeared into the wasteland to survive the next day with his car and his dog with him. Why did he do it?"

"Thelma and Louise could have turned themselves in. They had justifiable reasons for all that they had done. Why did they turn around and drive off that cliff?"

That's the draw of antiheroes. When we see a typical hero, we know they're going to do the right thing and save the day — we expect it. With antiheroes, we're not too sure they'll waste their time helping others. And we wonder how they can possibly walk that straight line long enough to save the day.

Developing and writing antiheroes isn't just about creating a cranky character who goes against the grain. You have to decide what type of antihero you want to portray — and why. You have to figure out what antihero characteristics you're going to apply to them — and why. You have to figure out where they stand on what lines of morality — and why. And finally, you have to figure out a way to draw the audience into this character and their story by forcing them to both loathe and love them — or love to loathe them.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!