How ARGO and LOOPER Screenwriters Handled Their Toughest Scenes

What are some of the toughest scenes that Hollywood screenwriters have struggled writing and how did they manage to prevail in the end?

Here we turn to Vulture's outstanding series of interviews, The Toughest Scene I Wrote, feature two particular stories that Hollywood screenwriters shared, and elaborate on the lessons that screenwriters can learn from them. We also share the script pages for these scenes.

Screenwriter Chris Terrio on Argo

Terrio won an Academy Award for the screenplay, which also won Best Picture.

Acting under the cover of a Hollywood producer scouting a location for a science fiction film, a CIA agent launches a dangerous operation to rescue six Americans in Tehran during the U.S. hostage crisis in Iran in 1979.

In the screenplay, Terrio had to tackle one of the most challenging scenes that screenwriters face — multiple characters talking in the same location. These types of scenes are the most difficult because they need to be engaging and sustain the reader's interest — and for that to happen, there has to be conflict.

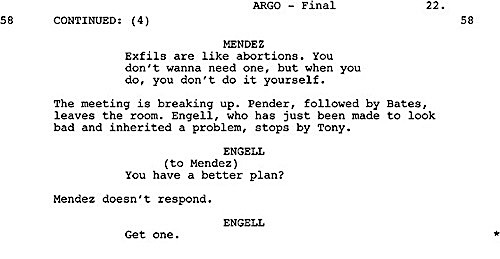

"I knew before I even attempted to write what became Scene 58 of Argo — a scene of nine men sitting in a conference room talking through various scenarios for a cover story to get Americans out of Iran — that the scene would be more difficult to pull off than any of the more (ostensibly) complicated set pieces in the film."

He went on to say, "A scene at Mehrabad Airport in 1979 is, by comparison, easy to write, because the story can be told through images: a portrait of the Ayatollah glowering over a crowd; the glimpsed tragedy of a refugee woman being yanked away from her husband. It’s the juxtaposition of image against image, as any good Bolshevik filmmaker knows, that tells the story; yet in a conference room, there’s nothing to cut to except the actors’ faces. The writing in a scene like this is, in effect, naked. The tension has to come from the audience’s awareness of subtle shifts of power in the room."

Terrio struggled with the scene and how to convey that shift of power within the dialogue.

"I settled on the idea that Mendez would throw a spitball into the self-serious conversation by making a joke about giving the bicycle escapees Gatorade... Mendez would make his off-hand joke. The table would go silent. The attention of the room would shift to the court jester speaking truth to power."

It was a brilliant way to utilize just one single line to shift the conflict of the dialogue exchanges.

Another option that could have been explored was giving Mendez a physical reaction to what they were saying — the 'ole Show, Don't Tell version. Mendez could have overturned a table or threw a glass at the wall to break the discussion and position himself as an authority figure. In the context of this scene, that would have been a mistake.

All of these men were in a battle of wits. Everyone had their own idea, and they likely felt that their's was the best.

A physical reaction on Mendez's part would have been overkill — and it wouldn't have positioned himself on any higher pedestal. Most of the characters were either his peers or higher-level authorities. He needed to attack their ideas to take control of the conversation and offer his own solution (the airport).

And when you watch the film, this launches the story into the second act. Mendez has been faced with a conflict and has communicated his solution. They have to create new identities and get someone to get them on a commercial airliner out of the country.

He's catapulted into his journey (the second act) when he's challenged to create a plan to execute this proposed solution.

This scene teaches screenwriters two things.

The first lesson teaches writers how to handle difficult scenes where characters need to be talking but what they are saying has to still be compelling and the dialogue exchanges have to be filled with conflict to do that. These characters could have just been reciting expositional lines of the plan. Instead, Terrio injected a line that shifted the power to Mendez, establishing him as a character that knows what he's talking about.

The second lesson teaches screenwriters how to transition from the first act into the second, launching the concept of the script and sending the character on their journey. By page 22, we know the conflict, we know the capabilities of the protagonist, we know their proposed solution, and we're well on our way into the story.

Lesser scripts would still be in Iran and within the set-up of that story, and the introduction of the protagonist, through Page 22. In Terrio's script, things are moving. And that is exactly what screenplays need to do, especially when you're writing on spec.

Writer/Director Rian Johnson on Looper

Johnson wrote and directed what would go on to become one of the most original science fiction features of all time.

In 2074, when the mob wants to get rid of someone, the target is sent into the past, where a hired gun awaits — someone like Joe — who one day learns the mob wants to 'close the loop' by sending back Joe's future self for assassination.

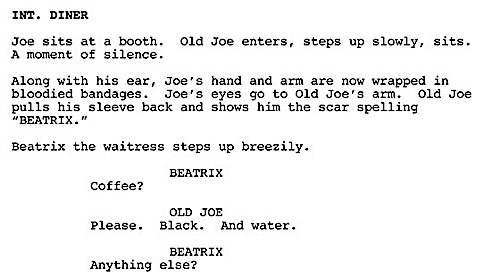

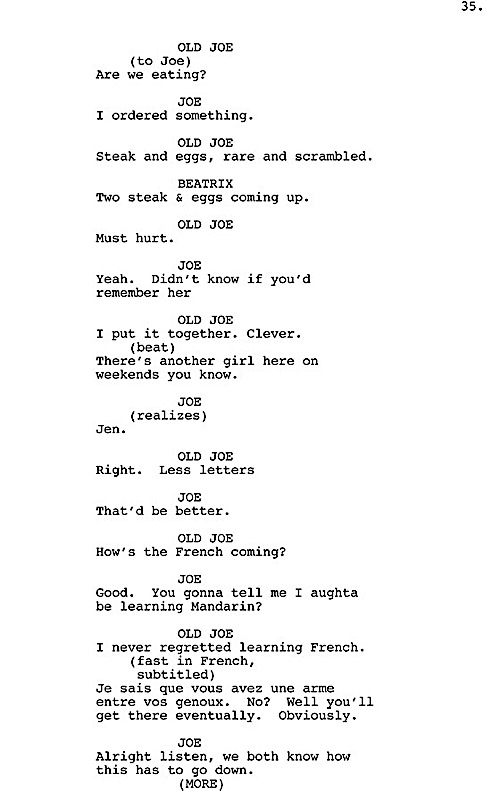

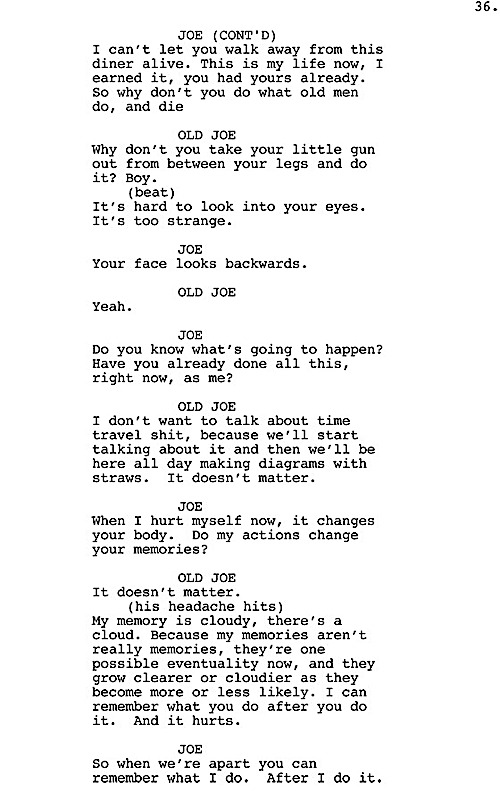

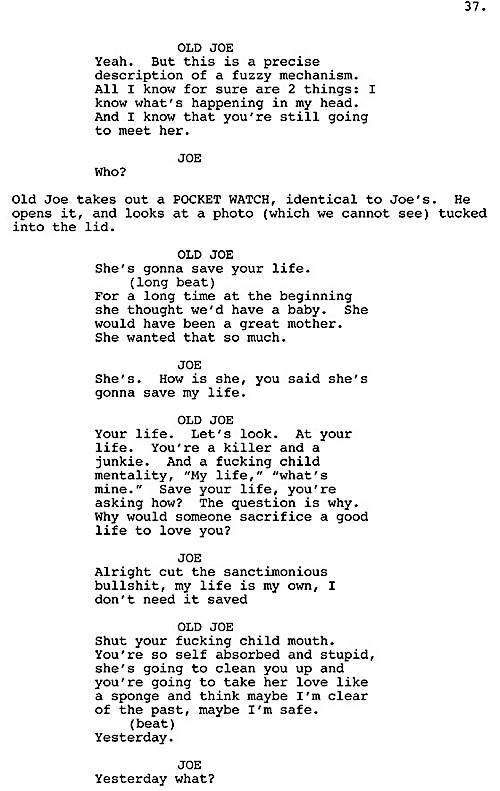

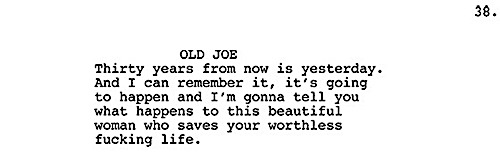

In the screenplay, Johnson had to develop a scene of dialogue exchange that perhaps no other notable screenplay had ever take on — an older and younger version of the same person, both of whom were adversaries.

"There was just a lot of weight on it for a lot of different reasons. Exposition-wise, it was the scene where we had to address — or choose not to address — all these questions about time travel in the minds of the characters and the audience. I didn’t want it to turn into a chalkboard scene, so balancing that with keeping these characters on track for what they actually want was tricky."

The key element that Johnson brings up is mentioning what the characters actually want. That's the most important element of any scene between two or more characters in a room. What do they want and how are they going about getting that?

"I knew what I wanted these two to butt heads about and I knew where I wanted it to end up, but I didn’t know much beyond that, so when I worked my way through the beginning of the script, I was kind of dreading when I would come to it. But then the nice thing about working for so long on the structure is that when it came time to actually write the scene, these people were ready to talk. The bigger problem is figuring out what not to have them say, pruning it back and keeping it tight and economic."

And that is so important for every dialogue scene — keeping it tight and economical while accomplishing what you need to.

Learn how to write great movie dialogue with this free guide.

"It was a real experience for me to work with a dialogue scene of this length and keep it as engaging as any of the action scenes, which was the goal."

Just over three pages of dialogue that covers a lot of difficult exposition. And it's written in a manner that oozes conflict. So the scene accomplishes two necessities at the same time, killing two birds with one stone. We're getting a lot of exposition, but it is hidden within the conflict between the two characters measuring each other up.

And beyond that, Johnson managed to brilliantly dodge a bullet that writers always have to deal with when writing science fiction. With one single line of dialogue, he avoided the need to explain the science of the concept — in this case, time travel.

Even Hollywood professionals have to problem-solve difficult scenes and sequences.

These are perfect examples of how to tackle common problems that screenwriters come across in their screenwriting. If you ever face similar issues in your scripts, you now hopefully know that all that it takes is some thought and effort to figure things out. It may not work the first time. It may not work the second or third. But you'll get there if you try.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!