Everything Wrong with Screenplays According to a Reader's Infographic

What helpful information could the minds of professional script readers unlock?

Script readers (yours truly included) — working for studios, production companies, management companies, and agencies — have a wealth of knowledge floating through their collective minds. We've seen and read it all. The good, the bad, the darn right ugly, and everything in between.

But what if we could take that information, experience, and knowledge and apply it to a visual aid that could help screenwriters learn the ins and outs of industry guidelines, expectations, likes, dislikes, and overall trends within the script market?

An anonymous script reader did just that.

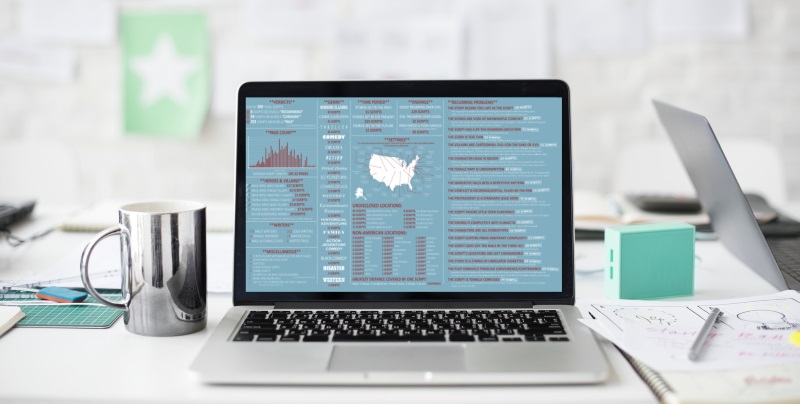

According to "Alex", as of 2013, he had read 300 scripts for five different companies as a professional script reader. He took his collected findings and created an interesting screenwriting coverage infographic.

Let's break it apart and see what can be learned from his research and notes — and then elaborate on extended lessons and collect some in-depth insight into what script readers can teach us about screenwriting.

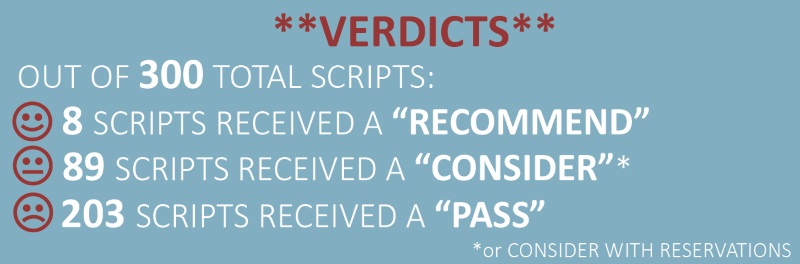

Roughly 2.6 % of those 300 screenplays received a Recommend. This is somewhat subjective, according to the reader's own reaction. However, screenwriters need to remember that script readers are also working on an objective scale as well, depending on what projects their bosses are — and are not — actively seeking.

Recommends are VERY hard to come by. In my time in Sony development, I read hundreds of screenplays and only had a handful of Recommends. I learned a lesson about recommending a script the hard way with my first official Recommend. The executive sat me down and asked me if I was sure that the company should spend millions of dollars on a period piece about a murderer and his dark exploits.

The lesson learned was that while a script may be very well written with even an excellent story and atmosphere, it may not be an investment worth the production costs of period costumes and sets — especially not one carrying the grandeur of a true story or existing intellectual property to help draw in the audience. A sad truth, but in the end, it is a business.

The 29% of Considers is a somewhat high average, but every script reader has their lucky streaks. When a script reader offers a Consider, they're essentially saying that both the writer and the script have some promising elements. Perhaps the script could be rewritten with the company's wants and needs in mind? Perhaps the writing is strong enough to consider the writer for assignments? Most Considers usually don't go anywhere, but every now and then one or two writers may be brought in for a general meeting.

66% of Passes (a hard No) is also somewhat of a high average. Usually, the Passes are in the ninety percentiles. Passing on a script means that either the script's story was horrible, the writing was horrible, or the concept alone just wasn't for the company. If Disney is given a hard R-rating script with blood, gore, sex, and foul language, chances are it's a Pass no matter how great the script may be — although if it was outstanding, the script may be passed to the right people and places through industry networking.

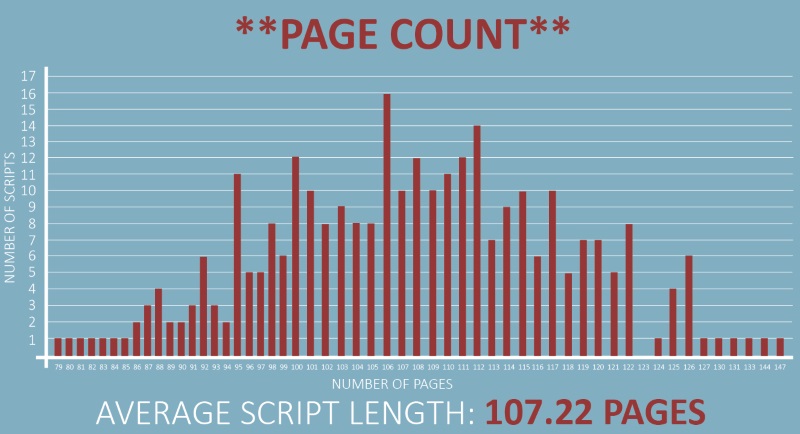

As of 2013 (the year this infographic was created), it's clear that most of these screenwriters were wise enough to avoid the mistake of submitting scripts over 120 pages. That general gray area between 120 and 129 spiked a little bit — as a screenwriter I've been guilty of that myself. Some stories call for just a little more.

But know that while the page count isn't an exact science — as far as minutes to screen time — it is often perceived as a red flag, and sometimes an annoyance, to the script reader that has a stack (or computer folder these days) of scripts waiting to be read. Most scripts that go beyond 120 pages are overwritten. Don't assume that yours is the exception. If you find yourself high on the page count, do your best to cut it down. Yes, you may have to slay some of those darlings you love so much. But remember that even the top 1% of screenwriters — the big moneymakers — have to do that with every script they're assigned to write. Even the Oscar-winners.

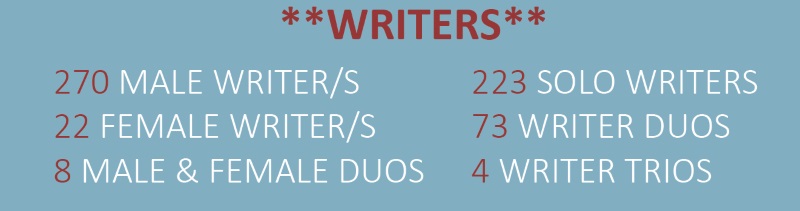

It's 2018 at the date of this article — and it's clear that these 2013 numbers represent the past, with current numbers now in favor of seeing more female heroes in more than 5%, 9%, and 11% of the scripts in the current market. I don't have the exact number, but it's clear that there are more female screenwriters getting their scripts read and more screenplays featuring women in lead roles as both protagonists and antagonists.

Speaking of male versus female percentages, as I stated earlier, these 2013 numbers are in the past. More female writers are breaking through. You can see it in contests, fellowships, the trades, and even in the theaters. 2018 is looking great and the future seems to be getting brighter and brighter as well with a more diverse group of screenwriters getting a chance to have their scripts read.

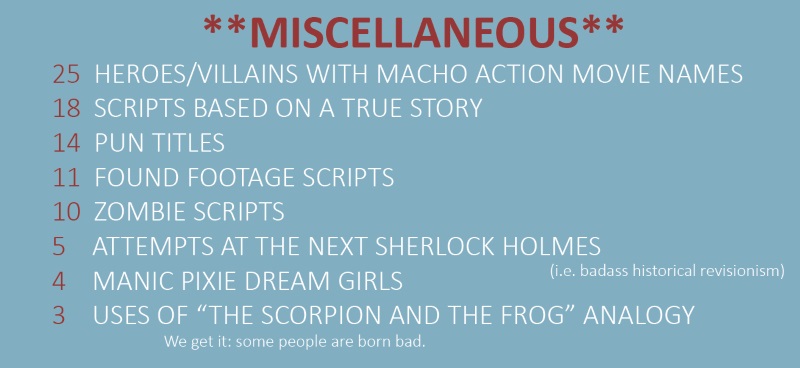

These miscellaneous numbers are likely a sign of the 2013 trends or lack thereof. Found footage and zombie scripts have fallen by the wayside. The context of what companies the reader that created this infographic was working for needs to be applied as well.

Some fun info nonetheless.

This graphic is a good representation of the current market averages. Horror movies and thrillers are all the rage, especially after the success of original screenplay concepts like Get Out and A Quiet Place.

Black comedies, westerns, and original disaster flicks are hard to sell most days. They have to truly stand out with original, unique, and intriguing takes.

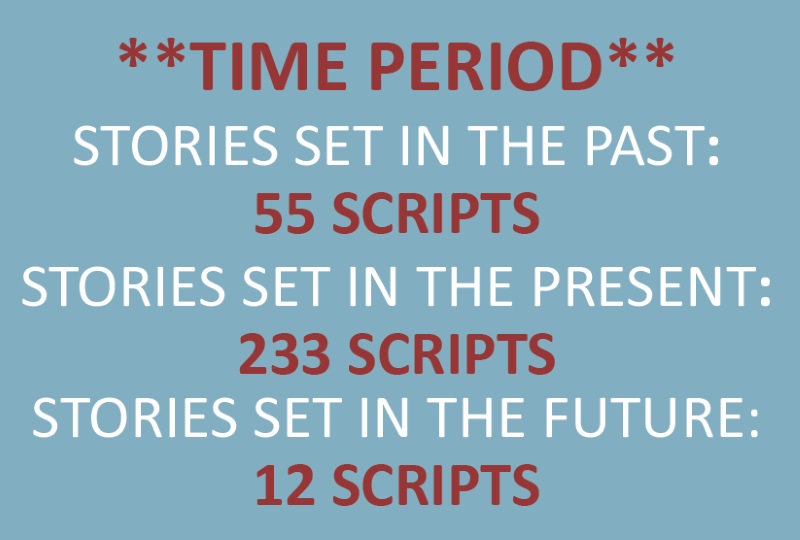

Studios and production companies have always been cautious with period pieces and future scripts. Past and future time periods only add to the overall production costs. From a business perspective, that's a risk, so the script better be outstanding and original enough to make up for those added budget costs. A majority of period pieces that come through Hollywood are based on true stories, so that may be why the number eclipses stories set in the future.

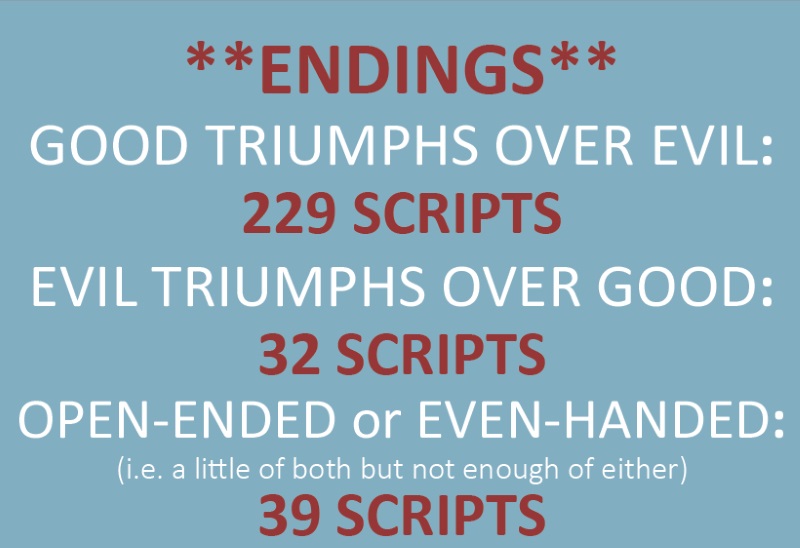

In the end, as the lights come up, most audiences want to walk out of the theater feeling some type of positive emotion. Writing scripts where good triumphs over evil is a pretty easy way to offer that to audiences. When evil wins in the end, it's often found in certain genres where the writers and filmmakers are seeking to create that lasting shock effect — look no further than the thriller and horror genres to find most of those types of stories. Cautionary tales can have that same effect and can be found in the drama and crime subgenres as well.

As a reader, I either want to be truly shocked and feel uneasy in that way or I want to close that script feeling like I've seen a character I grew to love triumph over the conflicts they faced. Anything in between is usually disappointing.

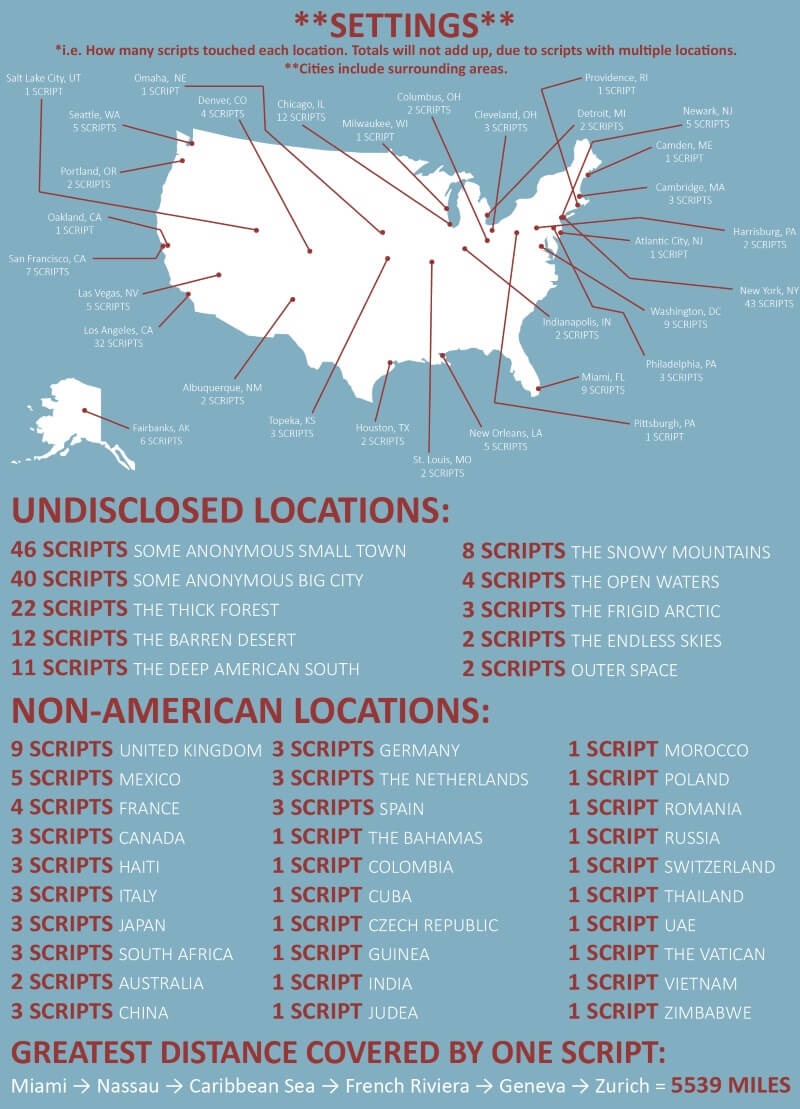

The key percentages here are the ones involving the anonymous small town or big city. If you're writing an original script it's always advisable to have the location set within an anonymous or non-specific setting. Once you type Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Paris, or any specific location, you're pigeonholing your script. If the screenplay is strong enough, yes, the powers that be can and will change the location to whatever their desire. But do your best to eliminate any and all red flags within your script. Don't give them a reason to say no.

Make sure the script has to be in South Africa, Japan, Spain, Baltimore, Philadelphia or some Wisconsin small town called Belleville. If not, EXT. SMALL TOWN - DAY will suffice.

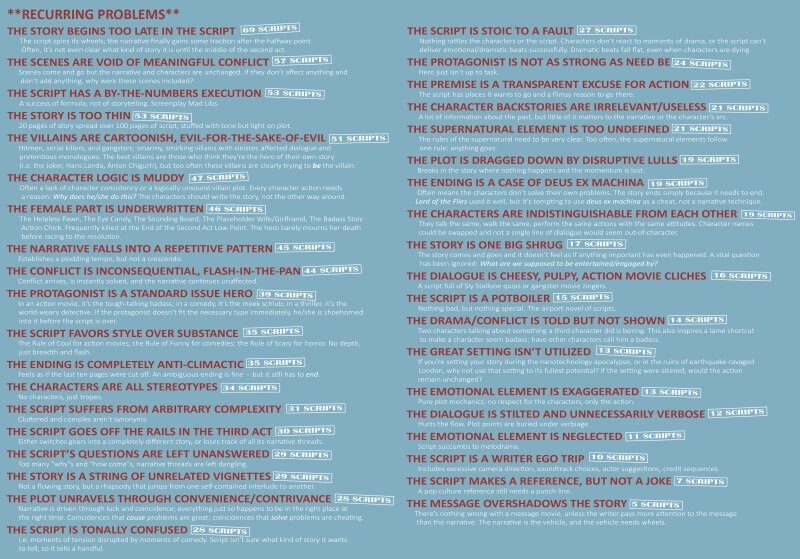

This part of the infographic is the big one, literally and figuratively. Here is the general breakdown of what is wrong with screenplays in the eyes of professional readers. While this information is based solely on one reader's coverage, I can sleep soundly agreeing with almost each and every one of these points and the ranking they fall under.

So from the biggest problem (#1) to the smallest (#38), check out what most screenplays are doing wrong on average (read this bigger graphic for details on each):

- The story begins too late in the script (69 scripts)

- The scenes are void of meaningful conflict (57 scripts)

- The script has a by-the-numbers execution (53 scripts)

- The story is too thin (53 scripts)

- The villains are cartoonish, evil-for-the-sake-of-evil (51 scripts)

- The character logic is muddy (47 scripts)

- The female part is underwritten (46 scripts)

- The narrative falls into a repetitive pattern (45 scripts)

- The conflict is inconsequential, flash-in-the-pan (44 scripts)

- The protagonist is a standard-issue hero (39 scripts)

- The script favors style over substance (35 scripts)

- The ending is completely anti-climactic (35 scripts)

- The characters are all stereotypes (34 scripts)

- The script suffers from arbitrary complexity (31 scripts)

- The script goes off the rails in the third act (30 scripts)

- The script’s questions are left unanswered (29 scripts)

- The story is a string of unrelated vignettes (29 scripts)

- The plot unravels through convenience/contrivance (28 scripts)

- The script is tonally confused (28 scripts)

- The script is stoic to a fault (27 scripts)

- The protagonist is not as strong as need be (24 scripts)

- The premise is a transparent excuse for action (22 scripts)

- The character backstories are irrelevant/useless (21 scripts)

- Supernatural element is too undefined (21 scripts)

- The plot is dragged down by disruptive lulls (19 scripts)

- The ending is a case of deus ex machina (19 scripts)

- The characters are indistinguishable from each other (19 scripts)

- The story is one big shrug (17 scripts)

- The dialogue is cheesy, pulpy, action movie cliches (16 scripts)

- The script is a potboiler (15 scripts)

- The drama/conflict is told but not shown (14 scripts)

- The great setting isn’t utilized (13 scripts)

- The emotional element is exaggerated (13 scripts)

- The dialogue is stilted and unnecessarily verbose (12 scripts)

- The emotional element is neglected (11 scripts)

- The script is a writer ego trip (10 scripts)

- The script makes a reference, but not a joke (7 scripts)

- The message overshadows the story (5 scripts)

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!