Blade Runner: Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples on The Q&A Podcast

By: Jeff Legge

Warning: spoilers for the original Blade Runner, including its hotly debated ending, are discussed at length in this article.

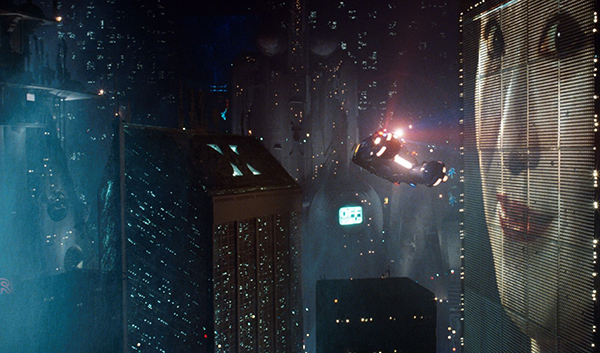

Hollywood's history is littered with examples of art from adversity. Still, few tales are as legendary as those surrounding the production of Ridley Scott's 1982 masterpiece, Blade Runner. Based on Philip K. Dick's existential science fiction novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Blade Runner follows the escapades of Rick Deckard, an LAPD cop played by Harrison Ford, tasked with hunting down and retiring four artificial humans known as "replicants", led by Rutger Hauer's Roy Batty.

During his investigation, Deckard visits the elusive Tyrell corporation and develops feelings for a female replicant named Rachael, whose artificiality and shortened lifespan casts a shadow over their blossoming relationship. Later, as their attraction grows, and the hunt for Batty reaches its famous, rain-soaked climax, Deckard discovers that his own humanity may be in doubt (depending on which version of the film you're watching, that is).

While the film itself is retroactively viewed as a masterpiece, it failed to light a fire with audiences and critics upon release until it was famously reevaluated years later on home video. Blade Runner was also an infamously tough production, with a tumultuous writing process, a difficult shoot, and a post-production cycle that eventually resulted in director Ridley Scott's removal from the project. The film was eventually salvaged in the form of multiple director's cuts, with the most recent 'Final Cut' generally considered to be the definitive version of the film. The changes run from surface-level adjustments, like the removal of the theatrical cut's much maligned voiceover, to deeply thematic narrative changes, such as lingering questions over Deckard's own humanity.

Even after 35 years, Blade Runner's mysteries, both behind and in front of the camera, remain an endless curiosity amongst cinema aficionados. And with its too-good-to-be-true sequel, Blade Runner 2049, now in theaters, we here at ScreenCraft decided the time was right to explore the fascinating history behind the original film. That's why we teamed with Final Draft and The Q&A Podcast with Jeff Goldsmith for a special screening of Blade Runner, followed by a deep dive discussion into the writing process with screenwriters Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples.

The full interview is embedded down below via Jeff Goldsmith's Q&A Podcast. For fans of Blade Runner (and great cinema in general), it's absolutely worth listening to in its entirety. And in the meantime, here are some of the most fascinating things we learned:

The full interview is embedded down below via Jeff Goldsmith's Q&A Podcast. For fans of Blade Runner (and great cinema in general), it's absolutely worth listening to in its entirety. And in the meantime, here are some of the most fascinating things we learned:

On working with Ridley Scott:

Fancher: "I loved Ridley from the get-go. He was inspiring, he was awesome. You catch a virus from him and you can’t stop."

Peoples: "I was coming in to do what Ridley wanted. He let me do a lot of things on my own, and that was fine, but really I was being brought on to move the script in the direction Ridley wanted."

Both Fancher and Peoples speak to the enthusiastic magnetism that underlined their collaborative relationship with Ridley Scott. Even with the film's tumultuous writing process (Fancher's resistance to Scott's demands ultimately led to him being removed from the project), both screenwriters praised the filmmaker for his unwillingness to leave any stone unturned.

After Fancher's firing, numerous production setbacks and a need for constant revisions led Scott to hire David Webb Peoples in an attempt to move the existing draft in a direction the filmmaker was more comfortable with. This collaboration would ultimately result in several additional drafts, including a final version that was as much Fancher's as it was Peoples'.

On constructing a romance between a human and a replicant:

On constructing a romance between a human and a replicant:

Fancher: (on Deckard and Rachael's first meeting) "I wasn't thinking about it like that - a relationship between a human and a replicant. It was somebody after somebody. Somebody looking to expose somebody, and somebody that didn't want to be exposed. Somebody that was defensive, that was up-tight about it, and how could she elegantly and nobly defend herself against this onslaught of this guy trying to get into her purse, so to speak."

Peoples: "I just sort of saw it as something to do with racism - Deckard's problem. Deckard had this rule, and because of that rule, he couldn't be attracted to her. And yet, begrudgingly, he was. And that meant he had to ask himself a lot of questions and struggle with a lot of stuff."

The film's central relationship between Deckard, a human (or so we're led to believe), and Rachael, a replicant, falls squarely under the romantic sub-category of forbidden love. Ford's Deckard struggles with his attraction on two levels. The first is professional - he's a replicant killer, after all. The second, however, is somewhat subtler. Specifically, Deckard's knowledge of Rachael's artificiality causes him a degree of cognitive dissonance.

As it turns out, both writers chose to approach this element of the script by anchoring it in something closer to reality.

On the film's much maligned voice-over, and their reaction to its subsequent removal:

Fancher: "Relief."

Peoples: "Very mixed. Because every time I was seeing the movie, I was seeing all the stuff that was good that was gone, and all the stuff that was different. I missed a lot of the voiceover, but I was glad to get the bad stuff out. There are just so many scenes and so many versions of that movie... It's an ongoing puzzle."

Among the most controversial elements of Blade Runner, at least in its initial incarnation, is its voiceover. A riff on Bogart-era film noir, the original film included a notoriously spotty narration courtesy of a sleepy-sounding Harrison Ford. Although Peoples wrote some of this narration himself, the majority was added by third-parties during the film's troubled post-production. The hope was that narration would not only enhance the detective-fiction stylings of the film, it would also provide clarity to the film's murky, slow burn-plot and existential themes. Scott was vocal in his opposition to the voiceover, which is partially why he was fired from the film during post-production.

The narration is notably absent in subsequent versions of Blade Runner, which goes along way in bringing the film closer to Scott, Fancher, and People's original vision.

On the film's multiple endings:

On the film's multiple endings:

Peoples: "I didn't think for a minute that Deckard was a replicant... But as I read it several years later, it says Deckard is a replicant even if that wasn't what I meant. And I wonder if that was from me when Ridley finally said 'Ha, Deckard's a replicant!'"

Fancher: "It's a bit ambiguous, you know. I always say one thing, and I'm sick of saying it. When the cat's out of the bag, the cat's out of the bag. Let's leave the cat in the bag."

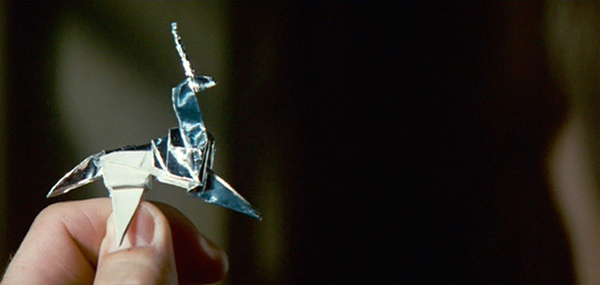

One of the most fascinating things about the multiple versions of Blade Runner is its ending - or endings. The original theatrical cut finishes on a somewhat bittersweet note, with Deckard and a doomed Rachael driving off into the sunset (with footage from Kubrick's The Shining intercut for the exteriors). Subsequent versions end at an earlier point - in Deckard's apartment - with the central character discovering an origami unicorn left by his colleague Gaff. The moment suggests that Deckard's earlier dream of a unicorn galloping through a forest could be an implanted memory, implying that Deckard himself may in fact be a replicant.

Curiously, neither of the film's writers doubted Deckard's humanity during the writing of the film. It was only through small revisions, minor on-set adjustments, and heavy re-edits by director Ridley Scott that the film's ultimate ending finally came to fruition.

Listen to the full info here:

-

For more from the interview, head on over to Jeff Goldsmith's official The Q&A Podcast website. And to read our interview with Blade Runner 2049 screenwriter Michael Green, click here.

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter and Facebook!

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!

On constructing a romance between a human and a replicant:

On constructing a romance between a human and a replicant: On the film's multiple endings:

On the film's multiple endings: