3 Ways Screenwriters Can Avoid the Paralysis of Analysis

Are you suffering from the paralysis of analysis in your screenwriting?

Screenwriters are surrounded by gurus, workshops, seminars, and countless screenwriting books that claim to have the secrets to writing the perfect screenplay. They read endlessly about the need for strict story structure, character arcs, formulas, outlines, note cards, etc. They are pulled this direction and that, as pundits declare that X needs to happen on this specific page and Y needs to happen on that specific page.

It leads to what Clint Eastwood has often referred to as the paralysis of analysis, which means that a screenwriter or filmmaker can all too often overthink the development and production of their project, and therefore lose some fantastic choices that could come in moments of inspiration.

Now, this isn’t a new term by any means. However, Eastwood brought it to the forefront of filmmaking when he told the story about the making of Flags Of Our Fathers, which Steven Spielberg produced and Eastwood directed.

Eastwood referenced Spielberg’s production of Saving Private Ryan, in which Spielberg shared that he decided against his normal storyboard process and instead created those now iconic opening battle sequences — complete with many different shots, angles, practical effects, and locations — on the day of shooting. Can you imagine? If you watch the opening of that film and see how complex, engaging, and brilliant those images are, it’s hard to believe that Spielberg made most of those decisions the day of. Eastwood utilized that style in Flags of Our Fathers and has ever since.

Rob Lorenz, one of Eastwood’s regular collaborators, stated in an interview with the Director’s Guild of America,"Analysis Paralysis means you go from the gut. That's one of the reasons he likes the first take so much. It's got that spontaneity."

Cinematographer Tom Stern reiterates, “Clint has [that paralysis of analysis] expression that he whips on me a lot because I have too many advanced degrees and it's gotten down to a kind of look he gives me over his nose when I start being analytical," Stern laughed. "He doesn't want to do that. He's spontaneous or improvisational. It's his spirit. He's very, very intuitive."

So how can screenwriters avoid the paralysis of analysis?

1. Know When to Quiet the Academic Voices

Most screenwriting books, seminars, and classes have an unfair advantage when it comes to talking about film theory. Hindsight is always 20/20. So when you take a book like Save the Cat or any other screenwriting book that presents a formula of sorts (in this case, beat sheets and page directives), all too often, you could just apply those formulas presented to almost any film, good or bad, and make them fit into that context. It’s very easy to then say, “See, these Oscar-winning films and these box office smashes used this formula, so…” Hindsight is always 20/20. And the funny thing is that even the poorly reviewed films and box office bombs out there have showcased the same “usage” of such formulas (at least in hindsight), and failed.

This isn’t to say that what Save the Cat or a guru like Robert Mckee says is useless, not by any means. It’s just that screenwriters need to understand that there is no “be all end all” answer to writing a successful screenplay. For every “proof in the pudding” example they offer, there are dozens more that have either tried the same and failed, or done something completely contradictory and succeeded.

Information is important. There are some fantastic books and seminars out there. They are often excellent food for the brain and get screenwriters thinking more about their craft. However, at some point, screenwriters need to let go, quiet those voices, and allow their own internal instincts to take hold.

2. Trust Thine Own Self

Storytelling is in our DNA as a species. We’ve been telling stories since the dawn of humankind. We still find etchings in caves, tens of thousands of years old, that display the core of storytelling; beginning, middle, and end. Stick figures holding spears (beginning), a beast appears before them (middle), and finally, the beast lies dead with spears sticking out of it as stick figures stand triumphant (end).

We’ve been ingesting stories through so many different platforms over so many different generations; books, plays, movies, radio, television, the internet, etc. It’s all there in our DNA and around us every day. We know beginnings, middles, ends, hooks, conflicts, character arcs, dialogue, silence, explosions, comedy, tragedy, scares, etc.

You need to trust yourself because, in the end, it’s just you in front of the screen with that blinking cursor staring back at you. Feed your brain, yes, but beyond that, trust your instincts.

3. Be Prepared, Not Overly Prepared

Too many screenwriters believe that they need to go into the writing process knowing Point A through Point Z and everything in between. That’s the worst thing that a screenwriter can do. Even though screenwriting is a blueprint for an eventual film where hundreds of people will collaborate to get it made, it still is an art form. It still is storytelling. If it weren’t, computers would be writing scripts for us (knock on wood).

Know the broad strokes. Know the major beats of the story and the characters. See that lousy trailer in your head that we talked about in 5 Habits to Get Those Creative Juices Flowing. But also know that much of that can, should, and will change and evolve as you write.

All screenwriters have different processes, sure. Again, there’s no “be all end all” answer. But understand that the real gems of any screenplay often come in those moments of inspiration, seemingly out of nowhere. You need to leave room for those moments. You need to leave some space for them. Not every answer to every question you have about the story and the characters needs to or should be answered in the outlining process. You shouldn’t know where every scene and every character is going to go and what is going to come next.

Having too many detailed outlines, character breakdowns, and beat sheets will only lead to one thing in the end — paralysis of analysis. At best, find a happy medium of being prepared, but not overly so.

“First, find out what your hero wants. Then just follow him.” — Ray Bradbury

These three points are simple, but key. Not only will they help you in your own process, but they’ll also serve the eventual script. Studio script readers are smart, and chances are they are screenwriters themselves who’ve read all of the books and know what’s out there. They can all too often tell which screenwriters followed various screenwriting book formulas and directives perhaps too religiously and which scripts were meticulously over-analyzed. Many times, those scripts feel hollow, empty, and by-the-numbers. It’s not the analytics that engages the reader — be it a studio script reader, producer, director, agent, manager, or talent — it’s the passion poured into the script. They see it. They recognize it. They love it. Save yourself and your script from the effects of paralysis of analysis.

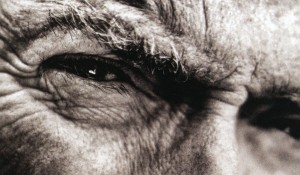

And if you find yourself possibly suffering from it, remember what Clint Eastwood’s cinematographer Tom Stern said about how the director would give him that certain look with those iconic eyes whenever he was too analytical. Just picture those intimidating eyes to quiet those academic voices, to trust thine own self, and to be prepared, but not overly prepared. If not for yourself, if not for your script, do it for Clint.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!