Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey Part 4: Meeting the Mentor

We dive into this archetypal story structure according to Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey and Christopher Vogler's interpreted twelve stages of that journey within his book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers?

Welcome to Part 4 of our 12-part series ScreenCraft’s Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey, where we go into depth about each of the twelve stages and how your screenplays could benefit from them.

The first stage — The Ordinary World — happens to be one of the most essential elements of any story, even ones that don't follow the twelve-stage structure to a tee.

Showing your protagonist within their Ordinary World at the beginning of your story offers you the ability to showcase how much the core conflict they face rocks their world. And it allows you to foreshadow and create the necessary elements of empathy and catharsis that your story needs.

The next stage is the Call to Adventure. Giving your story's protagonist a Call to Adventure introduces the core concept of your story, dictates the genre your story is being told in and helps to begin the process of character development that every great story needs.

When your character refuses the Call to Adventure, it allows you to create instant tension and conflict within the opening pages and first act of your story. It also gives you the chance to amp-up the risks and stakes involved, which, in turn, engages the reader or audience even more. And it also manages to help you develop a protagonist with more depth that can help to create empathy for them.

Along the way, your protagonist — and screenplay — may need a mentor.

Learn the best way to structure your screenplay with this free guide.

Here we offer three things a mentor character can do for your protagonist and your screenplay.

1. Create an Emotional Empathetic Bond Between Characters

The best stories have heart — and that applies to any genre. And for a story to have heart, the writer needs to create empathy for the characters.

When you introduce a mentor character — even in stories that don't necessarily follow every stage of Campbell's and Vogler's Hero's Journey — you're creating a relatable bond that readers and audiences can attach to on an emotional level.

People instantly relate to the bond of a parent and child or teacher and student — and often, those two types of relationships end up being one and the same within so many stories.

In Star Wars, Ben Kenobi teaches Luke in the ways of the Force. But he's also a father figure. Luke never knew his father. While he had his Uncle Owen, Ben Kenobi represents a connection to Luke's real father — which manifests as a direct father and son relationship.

In The Karate Kid, Daniel is the son of a single mother. We don't know what happened to Daniel's father, but we do know that he doesn't have one. Mr. Miyagi teaches him karate, but he also offers Daniel fatherly influence, helping Daniel get through challenging situations in his life that his mother can't quite relate with.

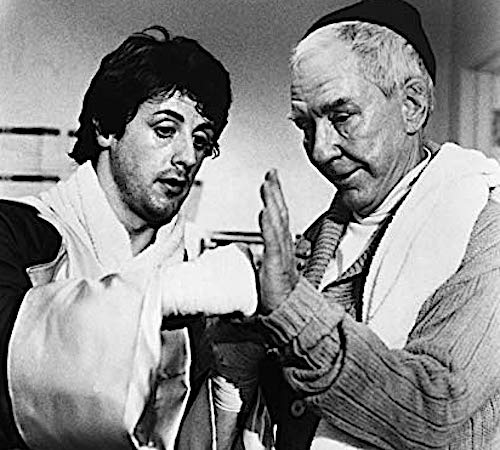

In Rocky, Rocky's parents are dead. He has no one — no family. His life as a fighter hasn't worked out. He's a club fighter by night, getting paid next to nothing. By day, he's the muscle of a loan shark. There's been no one to guide Rocky away from the bad path he has taken — except for Mickey. Mickey, like any father, calls Rocky out on his bad choices. He points out Rocky's faults. He does this as a teacher of boxing, with Rocky as his student, but there's a strong father-son bond that develops between them as well.

In Million Dollar Baby, Maggie is looking for someone to train her. Frank begrudgingly takes her on as a student. Their relationship develops. Maggie doesn't have a strong fatherly figure in her life, but it's Frank that is taking on a paternal bond with Maggie, substituting her for his estranged daughter.

A mentor character offers the reader and audience something to relate with, in terms of an emotional connection to the story and the characters.

2. Guide the Protagonist Through the Central Conflict

When the protagonist is first introduced within their Ordinary World, they are in a place of comfort or complacency. The best stories then take that character out of their comfort zone by throwing them into the metaphorical fire of an extreme conflict that rocks their world.

For some stories, this is an adventure that they are called to take on. For other genres, it's an emotional journey that they will be forced to deal with.

Mentors help them deal with their insecurities and weaknesses. They give confidence, knowledge, and direction. They build up the protagonist's hope and offer wisdom for them to reflect on as they deal with any inner and outer conflict. And sometimes they offer physical, supernatural, or metaphorical items that can help the protagonist succeed.

And sometimes the mentor isn't a character at all.

In Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the mentor present within the Hero's Journey interpretation of that story is the information embedded within Roy's mind by the UFO he encountered — constantly pulling him to a location that he's never been to through the image of a simple but mysterious shape that he sees.

Whether the mentor is a real person or something else, they also offer you the ability to use story elements to enhance the second act of your story. A protagonist taking on a conflict without any outside help can be engaging, but the second act can often falter.

When you have a mentor in the mix, the second act has more meat to it with this relationship between the protagonist and mentor, whether it's the preparation that the mentor takes the protagonist through or the conflict between the two as they do — preferably both.

3. Help You Introduce Story Elements, Themes, and Exposition Within the Screenplay

In Star Wars, we don't learn anything about the Force until Ben Kenobi shows up. Nor do we learn about Luke's father and the history of Darth Vader.

In The Karate Kid, we don't learn anything about karate or the philosophical angles of it that can help Daniel through his journey until Mr. Miyagi shows up.

In The Lord of the Rings, we don't learn anything about what can be done about the One Ring until Gandalf appears and explains things.

Mentors are an easy way for you, the writer, to offer information not only to the protagonists but to the reader and audience as well.

They can be present throughout the whole story, or they can appear briefly within the first and beginning of the second act. They can be physical items like maps or diaries. Or they can be supernatural intuition or scientific evidence that helps guide the protagonist to where they need to go.

They can also come in multiple forms within the story. In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy has multiple mentors throughout her adventure — Professor Marvel, Glinda the Good Witch, Scarecrow, Tin Man, the Cowardly Lion, and the Wizard. They all have a hand in helping her. And they all also have a hand in introducing the themes of the story.

Meeting the Mentor offers the protagonist someone that can guide them through their journey with wisdom, support, and even physical items. Beyond that, they help you to offer empathetic relationships within your story, as well as ways to introduce themes, story elements, and exposition to the reader and audience.

And remember...

"The Hero's Journey is a skeleton framework that should be fleshed out with the details of and surprises of the individual story. The structure should not call attention to itself, nor should it be followed too precisely. The order of the stages is only one of many possible variations. The stages can be deleted, added to, and drastically shuffled without losing any of their power." — Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers

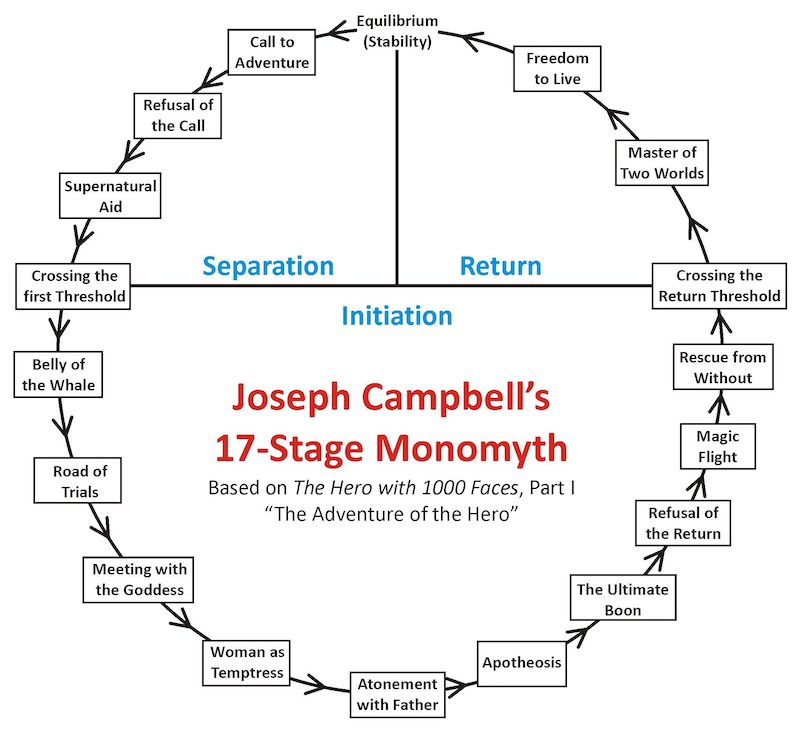

Joseph Campbell's 17-stage Monomyth was conceptualized over the course of Campbell's own text, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and then later in the 1980s through two documentaries, one of which introduced the term The Hero's Journey.

The first documentary, 1987's The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was released with an accompanying book entitled The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work.

The second documentary was released in 1988 and consisted of Bill Moyers' series of interviews with Campbell, accompanied by the companion book The Power of Myth.

Christopher Vogler was a Hollywood development executive and screenwriter working for Disney when he took his passion for Joseph Campbell's story monolith and developed it into a seven-page company memo for the company's development department and incoming screenwriters.

The memo, entitled A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was later developed by Vogler into The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters in 1992. He then elaborated on those concepts for the book The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

Christopher Vogler's approach to Campbell's structure broke the mythical story structure into twelve stages. We define the stages in our own simplified interpretations:

- The Ordinary World: We see the hero's normal life at the start of the story before the adventure begins.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is faced with an event, conflict, problem, or challenge that makes them begin their adventure.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero initially refuses the adventure because of hesitation, fears, insecurity, or any other number of issues.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor that can give them advice, wisdom, information, or items that ready them for the journey ahead.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their ordinary world for the first time and crosses the threshold into adventure.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero learns the rules of the new world and endures tests, meets friends, and comes face-to-face with enemies.

- The Approach: The initial plan to take on the central conflict begins, but setbacks occur that cause the hero to try a new approach or adopt new ideas.

- The Ordeal: Things go wrong and added conflict is introduced. The hero experiences more difficult hurdles and obstacles, some of which may lead to a life crisis.

- The Reward: After surviving The Ordeal, the hero seizes the sword — a reward that they've earned that allows them to take on the biggest conflict. It may be a physical item or piece of knowledge or wisdom that will help them persevere.

- The Road Back: The hero sees the light at the end of the tunnel, but they are about to face even more tests and challenges.

- The Resurrection: The climax. The hero faces a final test, using everything they have learned to take on the conflict once and for all.

- The Return: The hero brings their knowledge or the "elixir" back to the ordinary world.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!