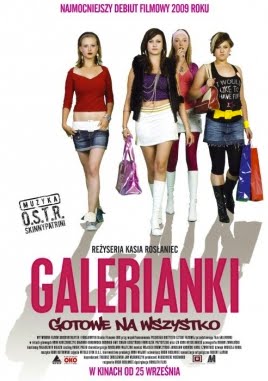

AFI Review: Baby Blues, A Moral Tale About Teen Pregnancy and Consumerism

An award-winning Berlinale favourite, Baby Blues mixes social realism with a Teen Vogue aesthetic to tell a moral tale about teen pregnancy and consumerism in contemporary post-communist Poland.

Made from a cast of total newcomers, Katarzyna Roslaniec’s second feature Baby Blues screams Generation Y. We open on teenage mum Natalia (played to neurotic perfection by Magdalena Berus) in a fashion-forward frock, pushing a kitsch baby pram, while breaking up with said baby’s father Kuba (Nikodem Rozbicki). Kuba continues to fall short on his newfound paternal duties but as a high school stoner in the midst of finals, it’s hardly a revelation. Nevertheless, Natalia presumably has baby Antek’s best interests at heart. Then cut to Natalia racing down a busy sidewalk in bright rollerblades pushing Antek’s pram at breakneck speeds while unceremoniously texting.

Such is the tone of Baby Blues: amused, appalled and empathetic for its high-strung protagonist, who as a brand new mum is struggling to balance maternal obligations with the prerequisites of a demanding social life. But Natalia is so attached to her baby Antek that she can’t bare to be away from him for more than a minute. In fact she seems like an altogether loving mother, better than her own mum Marzena (Magdalena Boczarska), who proves no help when she moves to Berlin for better prospects. In reality, Marzena abandoned Natalia for another corner of Warsaw in order to continue her own social life (surreptitiously cut short eighteen years before). Abandonment is a theme here and it repeats cyclically and returns viciously.

Having never completed high school and therefore being un-hirable, Natalia’s best foot forward is for baby Antek to model. But Antek proves challenging in front of the camera, as he bursts into tears whenever out of Natalia's reach. At the failed casting Natalia meets Martyna (Klaudia Bulka), a fashion model with a penchant for drugs, DJs and designer clothes. With nowhere to stay, Martyna is taken in by Natalia, in the hopes that another woman around the house will take the pressure off single parenthood. But Natalia merely commences on a downward spiral of drugs and partying that leads to drastic consequences.

For director Roslaniec, Baby Blues is a parable on consumerist culture. Baby Antek is fetishized not as a child but as a value object, a fashionable accoutrement for all social outings. To emphasize this, Roslaniec’s frames are a visual tease, filled with fashionable patterns, polka dots, stripes and swatches of color, emulating the very candy-colored fashion publications Natalia consults. Most of the time this is balanced by acute dramatic performances caught by long takes from a moving camera (think Four Months, Three Weeks and Two Days). But at times the scenes are too stylized, so much so that they lose their dramatic currency. A prime example is the fashion store Natalia takes a part-time job at which feels more like a ‘90s music video in tone and style. These scenes jar all the more and border on the cartoonish when the film takes a tonal shift towards tragedy in the third act.

But Roslaniec deserves praise for her ability to deal with heavy material with a bright watercolor palette. It’s both pleasurable and shocking to watch Natalia move through her arc of bad decisions, so much so one doesn’t know whether to route for her or scold her. At times the plot of Baby Blues can run contrived, but the final scenes are both shocking and rewarding.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!