18 Years Later: Why the CAST AWAY Script Works

How do you write a screenplay that has just one location and one character throughout the majority of the pages and still manage to keep the story compelling and engaging for an audience or script reader? Enter Cast Away.

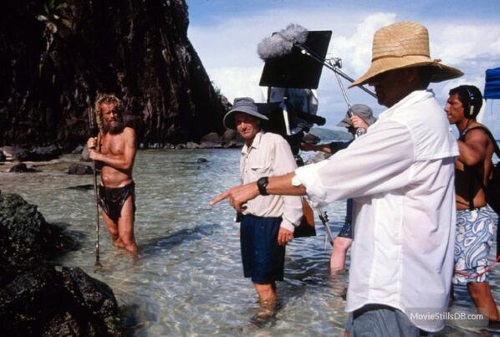

It's hard to believe that this film — reuniting Forrest Gump's Tom Hanks and Robert Zemeckis — debuted almost twenty years ago. Written by William Broyles Jr. (Apollo 13, Entrapment, The Polar Express, Jarhead, and Flags of our Father), the film tells the story of a FedEx executive that must transform himself physically and emotionally after his FedEx plane crashes into the ocean and then strands him on a deserted island where he's forced to survive.

In preparing to write the script, Broyles spent several days alone in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez trying to survive. He learned how to open a coconut, speared and ate stingrays, and even befriended a washed-up Wilson-brand volleyball. His failed attempts at trying to make fire ended up in the script as well.

These experiences led to an epiphany regarding this character. “That's when I realized it wasn’t just a physical challenge,” Broyles told The Austin Chronicle. “It was going to be an emotional, spiritual one as well.”

Broyles is a Vietnam veteran — an experience that led him to create the acclaimed Vietnam era series China Beach in the eighties. Broyles wanted to get into features, so he had the opportunity to pitch a Vietnam-era feature to Ron Howard. Howard liked the script enough to hire him to co-write Apollo 13. During the development and production of that film, Broyles and star Tom Hanks began initial discussions on a story that Hanks had wanted to tell.

The concept that was born during their discussions was to take a man of the times, comfortable in the predictability and connectedness of his professional and personal life, and knock him perilously off-course. Once stranded, he is forced to survive both physically and emotionally while eventually coming to terms with the path his life has taken. "What happens when your dreams don't come true?" Broyles asks. "That's a question all of us have."

"Sometimes it's better if your dreams don't come true," he says. "Because sometimes they're the wrong dreams."

The character that they came up with was Chuck Noland — a hybrid of Broyles' deadline-crunching workaholic and Hanks' sarcastic, likable Everyman. The two then began to share discussions with Robert Zemeckis, who had collaborated with Hanks on Forrest Gump. That trio would go on to develop the script together.

"Usually you get a movie star, a director, and a writer, and you make a movie," Broyles says. "At least one of them is going to be unhappy, and usually it's the writer. But I can honestly say, all three of us made the movie we wanted to make."

The script was finished, and they went into production in 1999 for a 2000 release. The film went on to garner $430 million worldwide off of a $90 million budget, as well as a Best Actor nomination for Hanks.

But what is it about this script that has made the film stand the test of time as a contemporary classic?

It All Starts with a Great Title

The brilliance of the screenplay began when the title was conceived. We've written extensively about the importance of finding a great title for your screenplay — one that is void of cliche and offers a simple, clear, and concise statement of what the script is going to be about.

Read ScreenCraft's How to Write Screenplay Titles That Don’t Suck!

The title focuses on the core concept — at its barest of minimums. It refers to the protagonist, the type of protagonist, and also sells us on what the story and that protagonist's struggles are going to be. Being stranded on an island is an engaging concept that most have thought about at one time or another. The fantasy of it. The horror of it.

All of that is sold to the script reader and to the audience with that brilliant title — avoiding the mistakes of conjuring dense titles like The Tides We Share, Endless Time, or others that so many lesser writers would have conceived.

And the icing on the cake is something that many don't even see at first glance when reading that title.

The main character is a castaway, yes. Castaway is defined as a person who has been shipwrecked and stranded in an isolated place. But the film isn't titled Castaway — it's Cast Away. This gives the title a dual meaning. The character is a castaway, but he has been cast away from his love, his career, and his life.

It all starts with a great title.

The Off-Island Bookends: Risks and Rewards

The script opens with a prolonged build-up, showcasing Chuck's world as a FedEx executive, and his obsessions — both in his professional and personal life — with time. Time to him is precious. Every second must be productive because in this world there is never enough time, so one has to become a master of it. We see this in the way he manages FedEx package deliveries and shipments and as he manages juggling his work schedule with the love of his life, Kelly, during the holidays when work comes calling.

We are introduced to Kelly and their relationship. We see the dynamic they have with friends and family. And we learn that they are on the brink of marriage — making the ultimate commitment.

Once Chuck enters that FedEx plane, we know from the title of the movie that this reality is about to be shattered.

Flash forward to the end of the film — BEWARE OF SPOILERS, but you've had 18 years — and we see that Chuck has triumphantly returned. We are then offered an additional story act where we see the repercussions of Chuck's disappearance and survival. His return isn't the dream that he, nor the audience, had hoped for. Kelly is married with a child. Chuck has been missing for four years. They had a funeral for him. Life moved on without him.

This final act leaves us with the tease of a possible light at the end of the tunnel for Chuck as the beginning of the film (the package) comes full circle with Chuck's final delivery of the package that was marked with the same markings as that opening package.

Two sequences that bookended the story of Chuck's survival on the island — two sequences that would have likely been cut if the script was written on spec by an unknown, as opposed to being developed by the screenwriter, Tom Hanks, and Robert Zemeckis.

Screenwriting consultants, gurus, and pundits would have likely told a novice screenwriter to cut those bookends and just open the story with Chuck getting onto that plane and then ending it with castaway Chuck on his makeshift raft as a shipping boat appeared with "man overboard" alarms sounding.

They would have told that screenwriter — and in that context maybe rightfully so — to throw the character into the conflict quickly and dazzle script readers with an action-packed first five pages that would surely hook the reader. Instead, in reality, we had packages delivered, dialogue about the importance of time when delivering said packages, a love interest storyline, a holiday dinner with family and friends, etc. Do you think those scenes would have survived the rewrite of a novice screenwriter writing on spec?

They were clear story risks, even for the likes of Broyles, Hanks, and Zemeckis, but the rewards were outstanding in retrospect.

The opening bookend gave us a sense of Chuck's philosophy and how that would change once he was on the island — where he would have more time than he could have ever imagined. It gave us the relationship that forced him to continue to survive — his love for Kelly. And it gave us an added weight to the drama and emotion of watching this character struggle to survive, knowing what he was forced to leave behind.

The closing bookend gave us answers that we, the audience, would surely have craved for if the script would have ended with Chuck seeing the shipping boat — his savior and his ride back to his life and love. While that ending would have served the great purpose of allowing the audience to partake in the story as they discussed what could have happened when he returned, this script gave us those answers.

We were able to see the struggles Chuck had acclimating to the world again, complete with the comforts of ice in his drink, an endless array of catered food — unfortunately for him it was seafood — and a nice comfortable hotel bed that he couldn't bear to sleep in.

We were heartbroken to see that Kelly had moved on. She had a family. And just when we thought they'd end up together, she realized she couldn't leave her husband and child.

So we were rewarded with what we surely would have been debating had the story ended with his rescue. And for those that don't like loose ends all tied up, Broyles managed to leave one loose end for audience members to talk about around the "water cooler" by keeping Chuck at a crossroads — literally — with options of freedom to travel wherever he pleased or to chase the fate of that woman he just delivered a package to... a package that saved his life on that island.

Conflict, Conflict, Conflict

So we asked the opening question, "How do you write a screenplay that has just one location and one character throughout the majority of the pages and still manage to keep the story compelling and engaging for an audience or script reader?"

The simple answer to that is something that the writer managed to deliver every few pages — conflict, conflict, conflict.

To many writers and audience members, it may have been enough just to showcase the survival of this stranded character. But the real strength of this script was how the writer piled more and more and more conflict into the premise and onto the character.

It was bad enough he was stranded on this island after such dire circumstances. But the writer managed to keep us invested by offering new and ever-evolving conflicts during almost each and every scene.

Let's highlight almost every new conflict that the writer injected into the script after the already heavy concept of Chuck going through that horrific crash into the ocean.

Survival Gear is Lost

Chuck is in the ocean, underneath the water as the remains of the plane sink into the ocean depths. He's struggling to get to the surface as he inflates the inflatable life raft. As it carries him up to the surface, it's caught onto the wreckage by the survival gear bag attached to the raft. Chuck struggles to get to the surface. This may be it for him, until the rope connecting the survival gear bag to the raft snaps, sending Chuck up. He screams in remorse, wide-eyed, knowing that he needed that survival gear. Conflict.

The Violent Waters

Okay, he's alive. The raft isn't damaged. He's floating on the surface of the water. However, a storm still rages on, sending towering waves crashing down upon him over and over and over again. Conflict.

Noises in the Dark

Okay, he survived the ocean and has managed to wash ashore on an island. We're injected with relief and hope. As he sets up camp, he's horrified to hear strange noises in the night. Thump. Thump. Thump. Can you imagine? Conflict.

Coconuts

What a relief. The noises were just coconuts falling from the palm trees above. And what does this present? Some hope. Food. Coconut water. But there's a catch. Coconuts are nearly impenetrable to the untrained castaway. Chuck struggles to find a way to open them. When he finally discovers a way to cut through the outer shell, he realizes that the actual coconut within is just as difficult to open to get to the food and liquid inside.

When he finally cracks the shell, the water goes everywhere, forcing him to find a way to open them without losing the contents. Conflict.

Cut Feet

Okay, it was tough, but he got those coconuts open. Now he has water and some food. But he needs something more than coconut to survive. And coconut is a natural laxative. So he goes fishing. However, his feet are unprotected, and the coral reef rips into the soles of his feet. He's forced to make some makeshift shoes with socks, a sweater, and some leaves for padding. Conflict.

Dead Body

So his feet are taken care of, for the short term at least. But what's that floating near the beach? Chuck runs into the water to discover one of the crew from the doomed flight. It's a terrifying sight for someone that likely has never seen a dead body as a result of such violence and tragedy. He's now tasked to bury the body, leading to some emotional conflict as well.

Shoes

The minor silver lining to the discovery of the dead crew member is Chuck's chance to protect his feet with some shoes taken from the dead body. Perhaps taking inspiration from Die Hard, Chuck discovers that the shoes are far too small for him. A minor conflict, but conflict nonetheless.

Lack of Water

Chuck manages to make some sandals out of the shoes and goes searching for water. It's clear that water is going to be hard to find. Conflict.

Light on Horizon

Chuck sees a flashing light on the distant horizon. It's a boat. He's saved! But wait, they can't see him. He doesn't have a fire lit yet, and his SOS signaling from the crew member's flashlight isn't enough. His chance at being rescued fades. Conflict.

Can't Escape the Island

When he continues to see the light on the horizon in the morning, he decides to take the inflatable life raft out in an effort to paddle towards the distant boat. The problem is, he can't escape the surf and the wave breaks surrounding the island. He doesn't have enough power to get past the final waves. Conflict.

Inflatable Life Raft Cut

If that isn't bad enough, he's forced into the reef by the towering waves. It rips, and all of the air escapes. The hope of ever paddling out again is lost. Conflict.

Coral Cut

To add insult to injury, another wave comes and forces Chuck's leg into the sharp coral. Blood and sheer pain follow. Conflict.

Stormy Winds

And to end his first full day and night on the island, another storm hits, forcing him to survive dangerous winds. Conflict.

That's just the first half of the screenplay. The rest of the script continues to pile the conflict on every few minutes, which in the context of the script accounts for every few pages.

As the story goes on, Chuck deals with more conflict in the guise of trying to start a fire and failing endlessly until he's cut, realizing that the search area is 500,000 square miles, his nagging toothache that was set up in the first act continues to get worse, his sanity is in question, after making a raft and escaping the island he loses the plastic that worked as his sail, then he loses his friend Wilson (see below), then his raft is in shambles, and then we're launched into the ongoing conflicts within the aforementioned bookend.

Conflict is everything, and the screenwriter manages to keep us engaged and invested by introducing endless new and evolved conflicts.

Wilson: Creative Narrative Solution

The one true struggle of a concept like this is how to communicate exposition. Despite what many believe, exposition is necessary. Not everything can be just shown. It's best to show more than to tell if you have options, but when you're dealing with a story about a single character alone in a situation, there's not much that you can do beyond having them talk to themselves — which is a clear and overused trope.

In the early stages of the script, they initially had Chuck have Gollum-like dialogue, with Good Chuck and Bad Chuck speaking out loud. Needless to say, that would have been a horrible creative choice.

Enter Wilson.

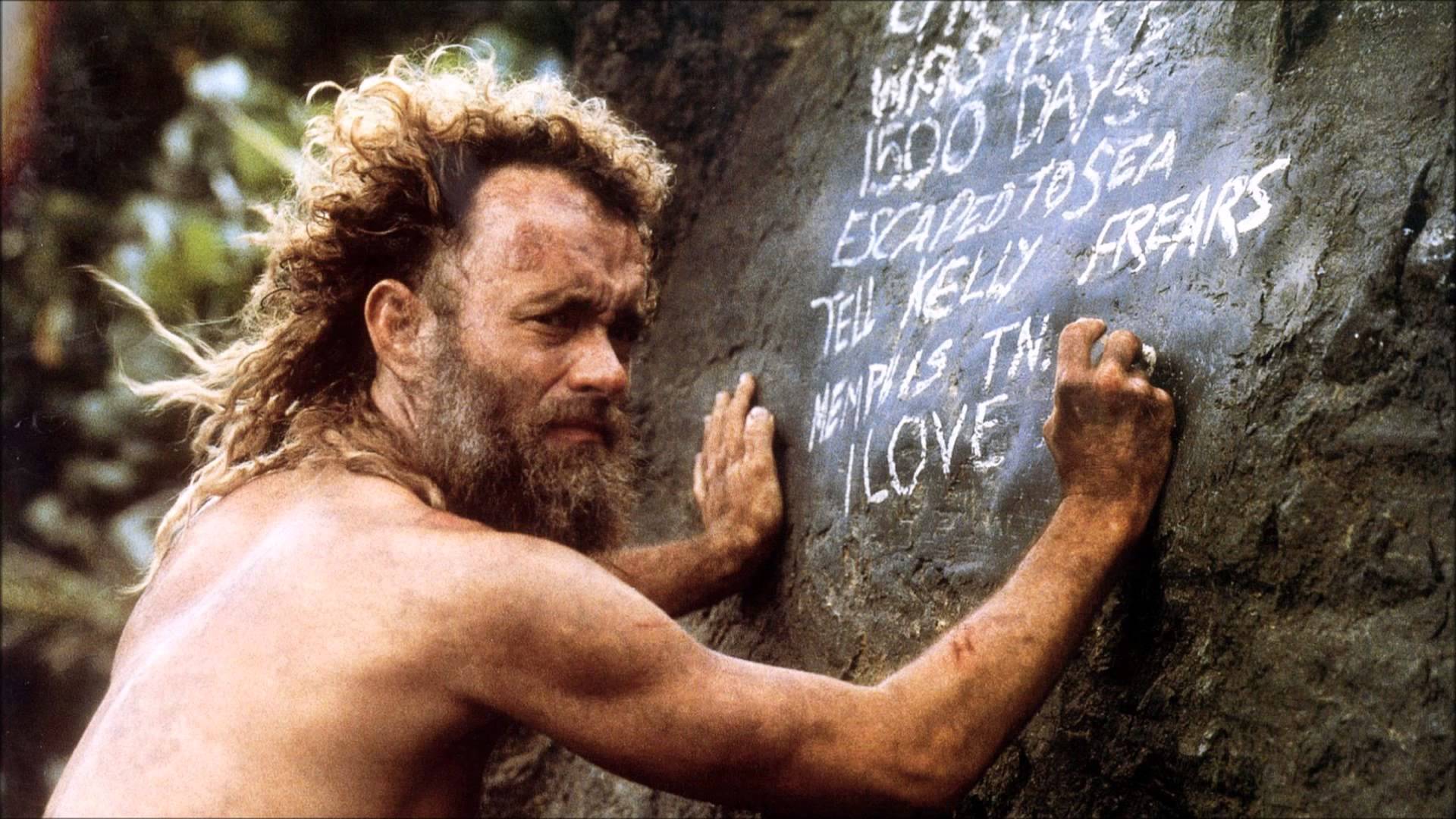

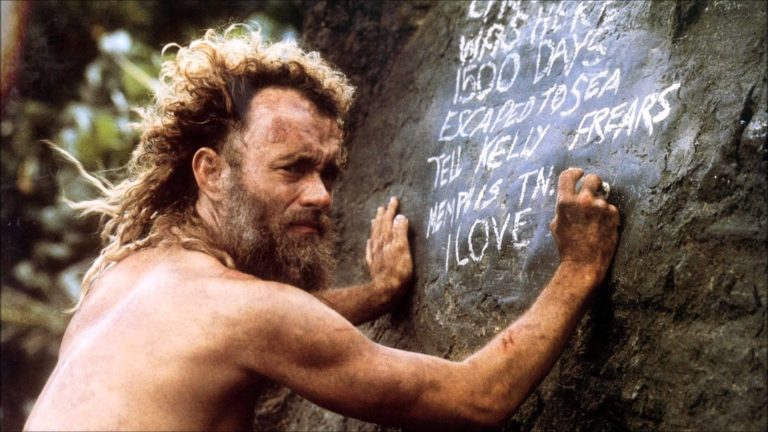

Yes, the volleyball character created when Chuck cut his hand, palmed the packaged ball he retrieved from FedEx packages that washed ashore, threw it, and then later looked forward to discover a face staring back at him — the result of his bloody handprint on the ball. Chuck then makes some minor adjustments, creating a more pronounced face.

Wilson stares back at Chuck as he goes about trying to make fire — to no avail at first. And we finally hear Chuck address another beyond grunts of pain and mumbles to himself.

A new character is born. Someone that Chuck can confide in. Someone that he can talk to. But even more important, the writer has created a vessel of exposition. Chuck can now communicate things like calculations of search area square miles and plans for making his escape.

And beyond that, he has a friend. As odd as it may seem to some, Wilson is his friend. They fight. They bicker. They ridicule. They judge. They make up. They show remorse towards each other.

It was a brilliant screenwriting decision to introduce this unique element into the story.

The Little Things

Most screenwriters forget the little things that can make a screenplay shine. The little nuances of foreshadowing, plants, and payoffs.

Read ScreenCraft's Best “Plant and Payoff” Scenes Screenwriters Can Learn From!

Early in the script, we're given little plants that will be either paid off or used as misdirects. The opening package with the angel wings (Chuck finds a package with the angel wings logo on the beach), Kelly's father's watch (she said her father had it on the South Pacific, where Chuck is eventually stranded), the toothache that bothers Chuck (Chuck later has to knock the infected tooth out in a rather painful scene to watch), the Swiss Army knife that Chuck has on his car keys (a misdirect because he never takes the keys with him), etc.

Then there are the thematic plants, payoffs, and foreshadowing. When the packages wash ashore, Chuck is given new life as he sorts them as he did during the opening scenes at the FedEx warehouse and trucks in Russia. This offers his character a taste of his life and renews hope as he opens packages that will help him survive — all but one.

Wilson's "birth" gives further hope to Chuck's survival. It's not until Wilson arrives when Chuck's fire making efforts finally pay off. It's not until Chuck finds Wilson after throwing him out of the cave in a fit of rage when Chuck finds the Port-A-Potty that will allow him to use the prevailing winds to push him past the impenetrable surf. It's not until Wilson lets Chuck go — to Chuck's utter dismay — when Chuck finally is rescued. And that lost friendship is transferred to a whale that Chuck discovers floating near his raft. The whale wakes him up when the shipping boat appears as Chuck is caught in a deep slumber.

It's the little things that matter.

Moments Coming Full Circle

It's always nice to end where we started, even if it is just thematic or visual.

Chuck is lost at sea at the beginning of the story. He is lost at a crossroads at the end of the film. Fate leads him where to go.

The angel wings package at the beginning is delivered to a wife's husband in Russia. A husband that is cheating on her. At the end of the film, she is single, likely as a result of such infidelity (the name of the ranch initially had a male and female first name in the beginning, by the end only the female name can be seen).

The tide of the ocean Chuck was lost in brought him the packages that helped him survive, including the sole package that he chose to leave unopened. The tide of the crossroads that Chuck was lost in at the end brought him the owner of that sole package — a woman that is undoubtedly going to be his next adventure.

If you can manage to bring your story and characters full circle by the end of the script, audiences will appreciate it as they reflect on the hopeful rush of experiencing your story.

Peppering your screenplay with conflict, plants, payoffs, foreshadowing, creative narrative choices, and moments coming full circle is essential to writing a successful script that truly delivers.

Cast Away managed to take what could have been a formulaic, by-the-numbers Robinson Crusoe story of survival and made it into something contemporary, unique, and original.

And that is why the script works.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!