Is Your Script "Based On" or "Inspired By" a True Story? What's the Difference?

True stories are some of the most desirable types of stories in Hollywood — second only to those based on Intellectual Property. But what are the dynamics of telling a true story? And how much freedom are you, the screenwriter, allowed when it comes to taking creative liberties within those stories?

Here we will offer simple breakdowns on adapting true stories for the screen and how you can find the best type of approach that fits the true story you want to tell.

Let's start with why true stories are so desirable in Hollywood.

Why Does Hollywood Love True Stories So Much?

True stories have power over the audience. As a species, we are genuinely curious. As a society, we're enthralled with stories that actually happened in real life — either because of our embedded curiosity within our DNA or because we love to live vicariously through the eyes of people that led an interesting life or lived through interesting events.

Hollywood knows this. They know what audiences love because they see the box office results, the streaming site numbers, and the pop culture tracking.

When a film or TV series is based on or inspired by a true story, there's an elevated level of interest.

Audience members that stumble upon these types of cinematic stories are intrigued.

- "This actually happened?"

- "Someone actually did that?"

- "I always wondered what the real story was like."

And that is why Hollywood loves true stories so much. If the audience likes stories like that, Hollywood wants to make stories like that. Plain and simple.

True stories are even better than Intellectual Property in the hierarchy of desirable types of cinematic stories. Why does Hollywood love Intellectual Property? Because there's a proven fan base already. The less they have to market something, the better. And that's exactly why true stories are so popular. You can use the true story tag as an easy marketing tool.

Okay, but what are the different types of true story screenplays that screenwriters can write?

The Four Different Types of True Story Scripts

Yes, that's right. There are four different types of true stories that screenwriters can research, develop, and write. And each of them comes with its own freedoms, restrictions, constraints, and benefits.

"Based on" a True Story

127 Hours

If you are writing a movie that is Based on a True Story, the expectations are that the characters, storylines, and a majority of the scenes that you present within the script are primarily based on actual occurrences. There are creative liberties taken for sure, but most of the depictions within the script are based on what actually happened and how it happened.

Read ScreenCraft's How to Master Creative Liberties in True Story Screenplays!

Films like Schindler’s List, The Right Stuff, Lincoln, 127 Hours, and Apollo 13 are excellent examples of screenplays that did their best to depict the actual true stories. The writers and filmmakers went to great degrees to capture the truth, allowing creative liberties to be taken within:

- The dialogue

- The combining of real-life people for cinematic amalgams

- The sequence of events

- The exclusion of events and people that were part of the real-life story

This is all done to portray the true story within the confines of a cinematic medium.

Overall, the story presented in the movie or series is as close to what really happened in real life as possible while allowing the screenwriter to structure a cinematic, dramatic, and compelling narrative. That is what sets this type of film or series apart from a documentary series.

"Inspired by" a True Story

The Inspired by a True Story approach offers screenwriters more leeway with the facts, allowing you the ability to take the real story and mold it into whatever feels like the best cinematic experience. The story is inspired by a specific story of a real-life person (or type of person), but more creative liberties are taken. And sometimes, the screenwriter, studio, or production company wants to focus on certain elements of the story and will use those focused elements to dictate where the story goes and what the characters say and do.

You may want to:

- Focus on the hilarity of the true story.

- Focus on the drama of the true story.

- Focus on the action of the true story.

- Focus on the horror of the true story.

Whatever the case may be, using the "Inspired by" tag allows you more freedom.

- You can create fictional characters representing variations or compilations of actual people and what they said or did within the actual story.

- You can accentuate the truth and create additional events that better tie together the true story elements you're focusing on.

- You can cherry-pick what works for your vision and toss the rest in favor of creating the best cinematic story.

The Pursuit of Happyness is a perfect example of writers taking the central core of the true story and character and using them to launch an otherwise fictional cinematic story with a few facts mixed in. While the two lead protagonists were real, the events and other characters depicted within the film were often either fictional or highly accentuated versions of the truth.

"Based on" True Events

Here we forgo the true story tag and, instead, focus on a true event — which basically means that you're taking a historical event and creating a story out of it using primarily fictional central characters.

Names, people, locations, and happenings may be made up within the historical event's confines as a setting. And, yes, to enhance the desirable true story aspect that Hollywood and audiences love so much, you can populate your story with historical figures and events as well — usually using them as figureheads to further legitimize your telling of the true event(s).

Titanic is a primary example of this, although the "based on true events" is implied and never really used in the film's marketing.

Everyone knows the historical event of the Titanic sinking. And while there were plenty of real-life people that James Cameron could have written a "based on a true story" script with, he chose to focus on the event itself while allowing him the freedom of using fictional characters of his creation. This allowed him to have full control over characterizations, mini-events within the historical event, and the overall narrative of the story he wanted to tell.

There was no Jack Dawson, Rose Dewitt Bukater, Cal Hockley, or Brock Lovett. There was no Heart of the Ocean diamond necklace that was lost at sea when the Titanic sank.

However, Cameron was wise enough to use many real-life characters throughout the screenplay to legitimize the story of the Titanic that he wanted to tell. But they were used as figureheads within the script, with Molly Brown as close to what we got as a developed portrayal of a real-life person.

Had there been confirmed types of character stories like we saw with Jack, Rose, Cal, and Brock, the script would have fallen under the category of "Inspired By a True Story." Instead, James Cameron:

- Focused on the historical event

- Created fictional characters as the main protagonists and antagonists

- Used historical characters to accentuate the historical legitimacy of the story

But when you're "basing" a script on an actual event, your primary goal is to represent that event as accurately as possible — albeit by using primarily fictional characters.

"Inspired by" True Events

Screenplays don't come as loose with the term "true" as they do with stories Inspired by True Events. These scripts take a true event and tell a cinematic story with nearly all fictional characters and fictional macro events.

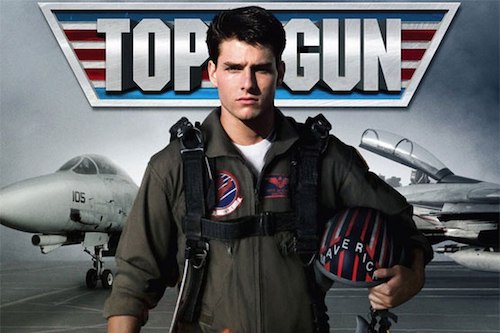

Top Gun never used the tag, but the feature was inspired by the true event(s) of a real flight school called U.S. Navy Fighter Weapons School — or TOPGUN — formerly based at Miramar Naval Air Station in San Diego. The movie was inspired by an article entitled "Top Guns" published in California Magazine.

No characters within the film are based on real people. They are all fictional — as are the events portrayed in the film. But the story and characters were inspired by the true events of the school.

Another offshoot of this is the Inspired by a True Case tag, where an actual criminal case loosely inspires events within the screenplay.

So, if a man killed a person in a certain stand-out way — per a public criminal case — a screenwriter could use that case as a basis for their story. If they tag the script as Inspired by a True Case, it may entice a buyer to take more interest. And, in turn, marketing a film or series as such may create more intrigue for the audience.

Many police procedural shows on television utilize real cases for inspiration.

But true stories or events aren't the only things you can write scripts tagged as Based on or Inspired by.

Enter your story into the ScreenCraft True Story & Public Domain Screenplay Competition. The Early Deadline is January 31st!

Writing Stories Based On or Inspired By Public Domain Stories

As we mentioned earlier, Intellectual Property is highly desirable in Hollywood — even more so than true stories. Having a script or two based on intellectual property increases your chances of getting your original interpretation of that property noticed.

However, most screenwriters can’t afford to buy the rights to the latest hit book or graphic novel — so they must turn to the Public Domain.

Disney does this all the time. Aladdin, Cinderella, Frozen, and so many others are all stories that exist in the public domain, but other famous stories, like Dracula and Robin Hood have also made their way into the hands of countless screenwriters looking to offer a fresh take on a timeless tale.

Jason Fuchs, the writer behind Pan, told ScreenCraft the story of being in a studio meeting for another screenplay. They asked him, “If you could write anything next, what would it be?” He quickly mentioned Peter Pan. He had no script written, just an idea that he had floating around in his head for years. He had pitched it to other studios to no avail. When he pitched it to this executive, she quickly said, “Oh, we’ll do that.”

Fuchs stated, “A script that I pitched at the beginning of summer 2013, was suddenly beginning principal photography in the last week of April 2014.”

And this happened largely because the material was based on one of the most renowned and recognizable intellectual properties — Peter Pan.

Just as with true stories, you can either write scripts "Based on" or "Inspired by" intellectual property that is now available through the Public Domain.

What Is the Public Domain?

The Public Domain refers to properties available for anyone to utilize, thanks to copyright expiration, copyright loss due to loopholes and mistakes, death of the copyright owner, or failure for the copyright owner to file for the rights or extension to those rights.

According to Stanford University Libraries:

Copyright has expired for all works published in the United States before 1923. In other words, if the work was published in the U.S. before January 1, 1923, you are free to use it in the U.S. without permission. As an example, the graphic illustration of the man with mustache (below) was published sometime in the 19th century and is in the public domain, so no permission was required to include it within this book. These rules and dates apply regardless of whether the work was created by an individual author, a group of authors, or an employee (a work made for hire).

Because of legislation passed in 1998, no new works will fall into the public domain until 2019, when works published in 1923 will expire. In 2020, works published in 1924 will expire, and so on. For works published after 1977, if the work was written by a single author, the copyright will not expire until 70 years after the author’s death. If a work was written by several authors and published after 1977, it will not expire until 70 years after the last surviving author dies.

It’s important to note that public domain characters and properties that screenwriters pursue have the danger of infringing on general trademarks from other interpretations of public domain content. While Norse mythology characters are obviously public domain, you can’t emulate Disney/Marvel’s Thor character trademarks from the comics and Marvel Cinematic Universe movies. You would have to tell your own very unique and different version of the story and character. One that doesn’t infringe on Disney/Marvel’s trademarks that they’ve established.

So when it comes to the legalities of what you plan on doing with anything from the public domain, proceed with caution despite the general stipulation that the property is available.

Be sure to read ScreenCraft’s 5 Things Screenwriters Should Know About Public Domain, written by an entertainment lawyer.

"Based on..."

When you base something on intellectual property that is part of the Public Domain, you're using specific property elements in the form of characters and events portrayed within those stories.

For example: You write your adaptation of The Wizard of Oz books using the characters, their names, and the events that happen within the book while taking creative liberties from the source material when necessary.

"Inspired by..."

When you are inspired by intellectual property that is part of the Public Domain, you're more focused on the types of characters and events portrayed within those stories.

For example: You don't use the name of Dorothy or Oz from The Wizard of Oz books, but you present a similar story about a girl that is whisked away from one planet to another planet where she must seek the aid of friends she's met on her journey to find her way home.

Read ScreenCraft's The Hottest Public Domain Properties For Screenwriters!

Whether it's for true stories or public domain stories, deciding whether you want to write a screenplay that is "Based on" or "Inspired by" such stories will dictate your approach and the freedoms, restrictions, constraints, and benefits that go along with it.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, and the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed starring Duane “Dog the Bounty Hunter” Chapman, Wesley Truman Daniel, Mickey O’Sullivan, John Victor Allen, and James Errico. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!