Two Essential Screenwriting Books Recommended by the Screenwriter of DIE HARD

!T’S NOT WR!T!NG, !T’S REWR!T!NG

November, 1975. The height of a national recession and a personal depression. I’d been fired from my job at a PBS TV station because I had unknowingly been renting film gear from an associate who was in fact sneaking the station’s gear out the back door for his equipment rental house, which existed only in his imagination and on the fake invoices he’d printed up to dupe me. Worse, the indie stoner film I’d shot on weekends with his purloined gear, while a film festival crowd-pleaser, had disappeared after a week in theaters when its distributor went bankrupt three days after the premiere, and my intermittent appearances in print barely covered groceries. The week of my birthday, the closest thing I had to employment was the hundred bucks my friend the infamous prankster Alan Abel spotted me to come to New York and aid him in his latest stunt, “Omar’s School For Beggars” — a non-existent institution which in true Abel style had duped national television and print media. That’s me, with the mustache, on the verge of breaking character:

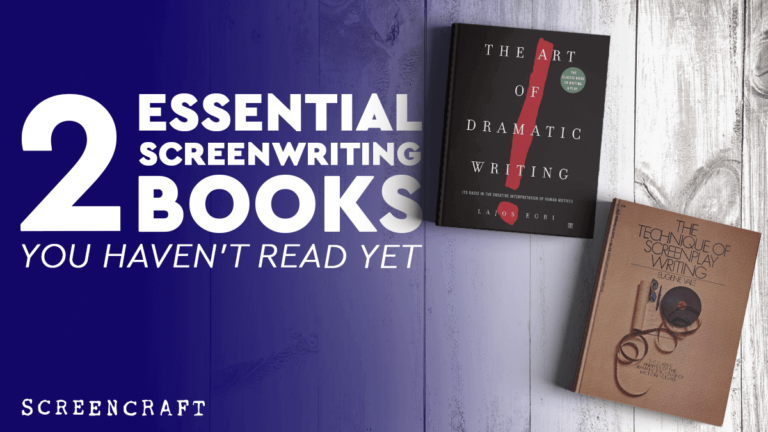

But unlike “Omar’s School For Beggars”, one actually existent institution in New York City was Greenwich Village’s Cinemabilia Book Store, tucked behind the Waverly Theatre, which in that pre-Amazon era was the only thing of its kind, an oasis of knowledge in all things filmic. So, after wrapping my part (above) in Alan AKA Omar’s “weekly panhandling class” (actually, the only class ever, staged to dupe broadcasters) in Cinemabilia’s stacks I discovered “The Technique of Screenplay Writing” by Eugene Vale (Published 1948, rev. 1972). As I skimmed its pages, the penultimate chapter struck me with its list of “common mistakes.” No less than one hundred and forty-two (!) mistakes were enumerated, including such mysterious movie ailments as “#25: Subintention misunderstood as main intention” and “#80: Failure to to imply execution of unopposed intention in lapse of time.”

I had no idea what either of these "mistakes" meant, but the idea that a script could be de-bugged was all the encouragement I needed; by the time the Metroliner returned me to Philadelphia (and another Omar stunt, this time in print) I was halfway through the book — by the end of the year, I was halfway through a Science Fiction-Body Horror spec script I had run through Vale’s gauntlet of trouble shooting… by March, I typed “The End” on it… and by April I was 3,000 miles away, sitting in front of Harve Bennett at Universal Studios who had — incredibly — bought my Science Fiction-Body Horror screenplay with the proviso that I remove all the body horror but keep the Science Fiction in order to better make it over into the prime-time family-friendly Six Million Dollar Man two-parter, “Deathprobe.”

“Your construction’s rock solid,” Harve began, “and your pace relentless… Vale?” A bit startled, I nodded. “He’s definitely the best as far as construction and staging, but…”

Now my confidence withered as scene after scene, Harve flipped from one dog-eared page to another, pronouncing “You have a jump on page 32…another jump on 37…. 49…“

“A jump?”

Harve lowered his reading glasses on their chain to give me a look as if I’d asked, “Adverbs? What are those?”

“Do you know Egri’s book?” My blank look about the volume spoke volumes. Harve turned. “Betty, get me a copy of Egri for Steven.” In what was an apparently regular event in Harve’s process, his secretary went to a closet and withdrew a copy from a stack of identical paperbacks of The Art Of Dramatic Writing: Its Basis in the Creative Interpretation of Human Motives.

Egri's book turned out to be the best road map to characterization I’d encountered either then, or since, with “jumps” his term for the dialogue potholes to avoid on the way. Better yet, his focus on characterization and exposition made it a perfect complement to Vale’s deep dive into construction and structure, and I’ve yet to find a single guide that equals this dynamic duo when consulted in tandem.[1] To this day, I cherish Harve’s recommendation and his advice as he handed it to me at his doorway: “Read this before you rewrite this script, and read it again before every other script you ever write for the rest of your life.[2] Oh, and by the way, your berserk space probe can’t be American or NASA will cut off our stock footage, make it Russian.”

And so with my first Hollywood script sale under my belt and “The Art of Dramat!c Wr!t!ing” (sic) under my arm, I began my official Hollywood career. I hope !t can do the same th!ng for you.

[1] A recent one that comes close is Sam Smiley’s 2005 extensive revision of his “Playwriting: The Structure of Action” : It has echoes of both, but its greatest recommendation to today’s screenwriters is its use of recent motion pictures as models (full disclosure: including my own), which may be more familiar to current readers than Vale and Egri’s 20th, 19th and even 18th Century examples.

[2] Obviously, I did, and after 45 years, it shows:

Steven E. de Souza is among the handful of screenwriters whose films have earned over $2 billion at the worldwide box office. He started his career as a Philadelphia-based writer for PBS, The New York Times, Premiere and other media outlets until he won a car and a color TV as a contestant on an LA game show -- and then talked his way into the office of several producers to leave behind some writing samples, leading to a contract with Universal Television as a story editor. From there, he moved into producing Knight Rider (1982) and then earned his first film credit, on 48 Hrs. (1982). That film, along with Commando (1985), Die Hard (1988) and Die Hard 2 (1990), established his reputation as a writer who could juggle both action and humor. That combination remains evident in all of his subsequent work, which expanded to include science-fiction (V (1984), The Running Man (1987), Judge Dredd (1995)``, horror (Tales from the Crypt (1989), Possessed (2000) and fantasy (The Flintstones (1994), Cadillacs and Dinosaurs (1993), Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life (2003). He has been nominated two times each for the Edgar Allen Poe award for best mystery screenplay and the Saturn award for best Science Fiction/Fantasy Film. In 2000 he was honored with the Norman Lear Award for Lifetime Achievement in writing. He has served a judge and generous mentor for the ScreenCraft Action & Adventure Screenplay Competition.

Steven E. de Souza is among the handful of screenwriters whose films have earned over $2 billion at the worldwide box office. He started his career as a Philadelphia-based writer for PBS, The New York Times, Premiere and other media outlets until he won a car and a color TV as a contestant on an LA game show -- and then talked his way into the office of several producers to leave behind some writing samples, leading to a contract with Universal Television as a story editor. From there, he moved into producing Knight Rider (1982) and then earned his first film credit, on 48 Hrs. (1982). That film, along with Commando (1985), Die Hard (1988) and Die Hard 2 (1990), established his reputation as a writer who could juggle both action and humor. That combination remains evident in all of his subsequent work, which expanded to include science-fiction (V (1984), The Running Man (1987), Judge Dredd (1995)``, horror (Tales from the Crypt (1989), Possessed (2000) and fantasy (The Flintstones (1994), Cadillacs and Dinosaurs (1993), Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life (2003). He has been nominated two times each for the Edgar Allen Poe award for best mystery screenplay and the Saturn award for best Science Fiction/Fantasy Film. In 2000 he was honored with the Norman Lear Award for Lifetime Achievement in writing. He has served a judge and generous mentor for the ScreenCraft Action & Adventure Screenplay Competition.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!