Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey Part 12: The Return

This is the final installment of our 12-part series of blog posts on a celebrated archetypal story concept. We dive into this archetypal story structure according to Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey and Christopher Vogler's interpreted twelve stages of that journey within his book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

Welcome to Part 12 of our 12-part series ScreenCraft’s Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey, where we go into depth about each of the twelve stages and how your screenplays could benefit from them. You can read the entire series via our free e-book which you can download here:

The first stage — The Ordinary World — happens to be one of the most essential elements of any story, even ones that don't follow the twelve-stage structure to a tee.

Showing your protagonist within their Ordinary World at the beginning of your story offers you the ability to showcase how much the core conflict they face rocks their world. And it allows you to foreshadow and create the necessary elements of empathy and catharsis that your story needs.

The next stage is the Call to Adventure. Giving your story's protagonist a Call to Adventure introduces the core concept of your story, dictates the genre your story is being told in and helps to begin the process of character development that every great story needs.

When your character refuses the Call to Adventure, it allows you to create instant tension and conflict within the opening pages and first act of your story. It also gives you the chance to amp-up the risks and stakes involved, which, in turn, engages the reader or audience even more. And it also manages to help you develop a protagonist with more depth that can help to create empathy for them.

Along the way, your protagonist — and screenplay — may need a mentor. Meeting the Mentor offers the protagonist someone that can guide them through their journey with wisdom, support, and even physical items. Beyond that, they help you to offer empathetic relationships within your story, as well as ways to introduce themes, story elements, and exposition to the reader and audience.

At some point at the end of the first act, your story may showcase a moment where your protagonist needs to cross the threshold between their Ordinary World and the Special World they will be experiencing as their inner or outer journey begins. Such a moment shifts everything from the first act to the second, allowing the reader and audience to feel that shift so they can prepare for the journey to come.

It showcases the difference between the protagonist's Ordinary World and the Special World to come. And, even more important, we're introduced to the first shift in the character arc of the protagonist as they decide to venture out into the unknown.

And it's within this unknown that the protagonist faces many tests and meets their allies and enemies — all of which define the meat of your story by introducing the conflict, expanding the cast of characters, and offering a more engaging and compelling narrative.

Once you've put your protagonist through those tests and once they've met their allies and enemies, they're going to need to Approach the Inmost Cave of the story — preparing to face their greatest fears and conflicts. This is an essential element of your narrative, allowing the reader, audience, and characters to catch their breath, reflect, review, and plan ahead for the conflict just over the horizon. And it allows you, the writer, to build the necessary tension and anticipation that you need going into the midpoint of your story.

Everything within the first act — and the beginning of the second — builds up to The Ordeal, which is the first real conflict that the protagonist must face. The Ordeal is the midpoint of your story that works as a false climax, taking your protagonist to the depths of despair. It offers you the ability to create an engaging midpoint climax that takes you into the third act. It ups the stakes within your story by taking away beloved allies and mentors. And it sets up the necessary transformation that your protagonist must go through in order to prevail.

And after your hero has gone through all of that, you may want or need to reward them with something that they can use to take on the final threat they face during the climax of your story.

The Reward offers the protagonist the added boost they need to propel themselves through the conflict they face during the climax of the story where they are facing their toughest challenge — be it physical or emotional. A special weapon, an elixir, some knowledge, an experience, or reconciliation are the five types of rewards that heroes need to prevail.

Once they've attained the Reward, it's time for the hero to get on The Road Back to their Ordinary World. The Road Back allows the hero — and the reader and audience — to see the light at the end of the tunnel, if not for a few brief moments. It then introduces more conflict, higher stakes, and reveals everything that is at risk going into the climax of the protagonist's journey.

And the climax of your hero's journey encompasses The Resurrection stage. It's not just about defeating the villain, winning the big game, getting the girl or guy, or accomplishing a goal. Your hero needs to be transformed by the end of the story. They need to be resurrected as a better version of themselves after having endured this long journey full of tests, obstacles, and hurdles. And their final test in this climax needs to be the ultimate challenge with the highest of stakes. That's how you end your script with a bang — both physically and emotionally, as far as whatever the story and genre may be.

And once they accomplish that, you can have your protagonist return to their Ordinary World.

Here are three reasons why your hero should make that return.

1. To Have the Story Come Full Circle

The reader and audience are on this ride with your protagonist. They empathize with them. The story creates a cathartic reaction. We want to see the story resolved. We want to witness some closure so that we know the character's journey has ended.

So what better way to accomplish that than letting them go back to their Ordinary World to either flaunt their success or show people that they've changed for the better?

In Willow, we see the titular protagonist return to his village a hero. When he left, he was considered a joke — a naive wannabe sorcerer. But now, he's welcomed with open arms as he showcases the knowledge and experience that he's learned. Oh, and he's saved the world from evil as well.

In A Bug's Life, after the grasshoppers have been defeated, Flick is welcomed back into the community as a hero instead of a hindrance. The ants are even using some of his inventions that originally caused the workers grief and chaos.

In Back to the Future, Marty returns to his Ordinary World, only to discover that he positively influenced his family's life as a result of his actions in the past.

Note: Scene shown in mirror image within the below video.

A cinematic story takes a reader — and later, an audience — on a ride. It may be a physical thrill ride or emotional rollercoaster, but, in the end, that ride must always come to a close. And it helps to give people a sense of closure to see the conflict of the story resolved. And there's no better place to do that than visiting the hero's Ordinary World once again — after all is well.

2. To Complete the Character Arc

When we follow a character for a long period of time, we want to see their character grow, change, or better themselves. It offers the reader and audience a sense of closure and catharsis.

When we put the protagonist back into their Ordinary World, it makes the reader and audience wonder how they'll react.

Have they changed?

Will they fall into the same pattern that they were in when they were introduced within their Ordinary World?

In Back to the Future Part III, Marty has learned to put his ego in check — a key theme throughout the second and third films.

In Toy Story, Woody has learned that new isn't necessarily such a bad thing. He handles change much better.

In The Matrix, Neo returns to the Matrix with his newfound powers and sense of consciousness. He's gone from an unknowing character to an all-knowing hero, ready to take on any threats.

The Return to the Ordinary World gives your protagonist the opportunity to prove that they've changed for the better, learned something, or have attained a certain power or piece of knowledge that will help them — and maybe others within their Ordinary World — take on any and all future conflicts.

3. To Allow the Reader and Audience to Live Vicariously

Because catharsis is so vital to the cinematic experience — that's why people go to the movies — having the hero return to their Ordinary World triumphant offers the reader and audience a chance to feel the glory of that return. And if it's not glory, it's a sense of calm, knowing that everything is going to be okay for the character they've lived vicariously through.

In Good Will Hunting, we're back to Will's Ordinary World. Yes, he's had a breakthrough with Sean. Yes, he has completed his court-ordered punishment. But Skylar is gone. Everything else in his life is better, but he lost out on the love of his life.

And now he's back in his routine — or so we think. It's another day. Will's friends arrive in his driveway. His best friend gets out and knocks on his door, ready to go through another day in their routine Southie lives.

But wait, Will's not home.

We feel that cathartic moment of going after the love of your life through the actions of Will. And we're left energized and inspired.

In Titanic, Rose has survived. She's back in a version of her Ordinary World, off of the Titanic. As she waits on the rescue ship, she sees her fiance and her mother, two forces of negativity that represent the life she was stuck in before she met Jack. And even though Jack is gone, we soon learn that she went on to live an amazing life full of adventure and intrigue. She's taken what she learned from Jack about life, and went on to live life to its fullest.

The message and center theme of the film offers the audience the cathartic feeling of the appreciation of life. We're left with a sense of wanting to be better and wanting to live life to its fullest. And we experience that vicariously through Rose.

When the reader closes your script or when the audience walks out of that theater, they go back to their Ordinary World changed — just like your protagonist has by returning to their Ordinary World and proving that they've changed themselves.

Not every story calls for the protagonist to return to their Ordinary World, but it's a wonderful tool to consider using within your cinematic tales.

And remember...

"The Hero's Journey is a skeleton framework that should be fleshed out with the details of and surprises of the individual story. The structure should not call attention to itself, nor should it be followed too precisely. The order of the stages is only one of many possible variations. The stages can be deleted, added to, and drastically shuffled without losing any of their power." — Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers

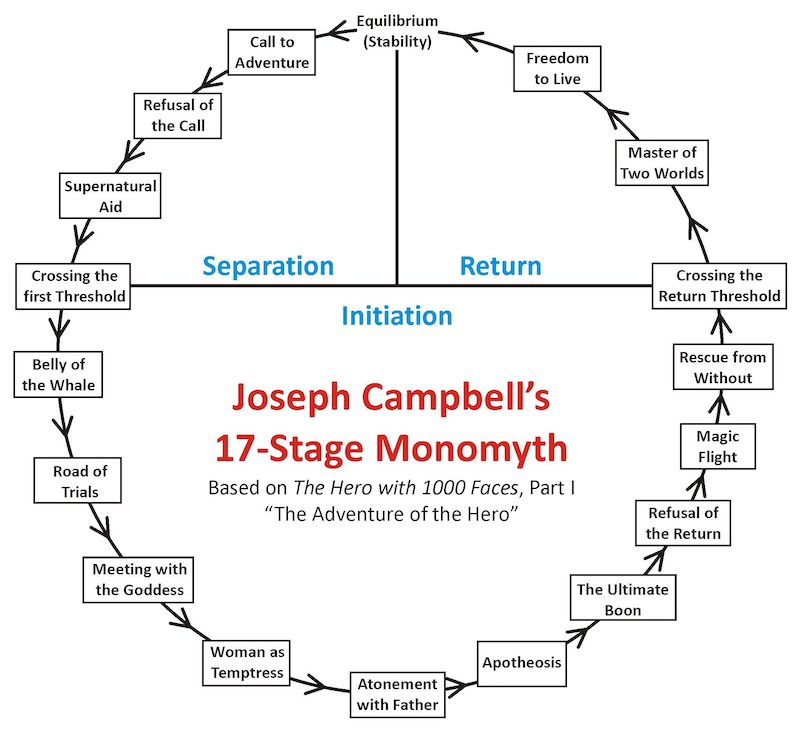

Joseph Campbell's 17-stage Monomyth was conceptualized over the course of Campbell's own text, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and then later in the 1980s through two documentaries, one of which introduced the term The Hero's Journey.

The first documentary, 1987's The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was released with an accompanying book entitled The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work.

The second documentary was released in 1988 and consisted of Bill Moyers' series of interviews with Campbell, accompanied by the companion book The Power of Myth.

Christopher Vogler was a Hollywood development executive and screenwriter working for Disney when he took his passion for Joseph Campbell's story monolith and developed it into a seven-page company memo for the company's development department and incoming screenwriters.

The memo, entitled A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was later developed by Vogler into The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters in 1992. He then elaborated on those concepts for the book The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

Christopher Vogler's approach to Campbell's structure broke the mythical story structure into twelve stages. We define the stages in our own simplified interpretations:

- The Ordinary World: We see the hero's normal life at the start of the story before the adventure begins.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is faced with an event, conflict, problem, or challenge that makes them begin their adventure.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero initially refuses the adventure because of hesitation, fears, insecurity, or any other number of issues.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor that can give them advice, wisdom, information, or items that ready them for the journey ahead.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their ordinary world for the first time and crosses the threshold into adventure.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero learns the rules of the new world and endures tests, meets friends, and comes face-to-face with enemies.

- The Approach: The initial plan to take on the central conflict begins, but setbacks occur that cause the hero to try a new approach or adopt new ideas.

- The Ordeal: Things go wrong and added conflict is introduced. The hero experiences more difficult hurdles and obstacles, some of which may lead to a life crisis.

- The Reward: After surviving The Ordeal, the hero seizes the sword — a reward that they've earned that allows them to take on the biggest conflict. It may be a physical item or piece of knowledge or wisdom that will help them persevere.

- The Road Back: The hero sees the light at the end of the tunnel, but they are about to face even more tests and challenges.

- The Resurrection: The climax. The hero faces a final test, using everything they have learned to take on the conflict once and for all.

- The Return: The hero brings their knowledge or the "elixir" back to the ordinary world.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!