Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey Part 11: The Resurrection

This celebrated archetypal story concept is explored here, according to Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey and Christopher Vogler's interpreted twelve stages of that journey within his book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

Welcome to Part 11 of our 12-part series ScreenCraft’s Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey, where we go into depth about each of the twelve stages and how your screenplays could benefit from them. But first, if you haven't already, be sure to download our free e-book while it's still available:

The first stage — The Ordinary World — happens to be one of the most essential elements of any story, even ones that don't follow the twelve-stage structure to a tee.

Showing your protagonist within their Ordinary World at the beginning of your story offers you the ability to showcase how much the core conflict they face rocks their world. And it allows you to foreshadow and create the necessary elements of empathy and catharsis that your story needs.

The next stage is the Call to Adventure. Giving your story's protagonist a Call to Adventure introduces the core concept of your story, dictates the genre your story is being told in and helps to begin the process of character development that every great story needs.

When your character refuses the Call to Adventure, it allows you to create instant tension and conflict within the opening pages and first act of your story. It also gives you the chance to amp-up the risks and stakes involved, which, in turn, engages the reader or audience even more. And it also manages to help you develop a protagonist with more depth that can help to create empathy for them.

Along the way, your protagonist — and screenplay — may need a mentor. Meeting the Mentor offers the protagonist someone that can guide them through their journey with wisdom, support, and even physical items. Beyond that, they help you to offer empathetic relationships within your story, as well as ways to introduce themes, story elements, and exposition to the reader and audience.

At some point at the end of the first act, your story may showcase a moment where your protagonist needs to cross the threshold between their Ordinary World and the Special World they will be experiencing as their inner or outer journey begins. Such a moment shifts everything from the first act to the second, allowing the reader and audience to feel that shift so they can prepare for the journey to come.

It showcases the difference between the protagonist's Ordinary World and the Special World to come. And, even more important, we're introduced to the first shift in the character arc of the protagonist as they decide to venture out into the unknown.

And it's within this unknown that the protagonist faces many tests and meets their allies and enemies — all of which define the meat of your story by introducing the conflict, expanding the cast of characters, and offering a more engaging and compelling narrative.

Once you've put your protagonist through those tests and once they've met their allies and enemies, they're going to need to Approach the Inmost Cave of the story — preparing to face their greatest fears and conflicts. This is an essential element of your narrative, allowing the reader, audience, and characters to catch their breath, reflect, review, and plan ahead for the conflict just over the horizon. And it allows you, the writer, to build the necessary tension and anticipation that you need going into the midpoint of your story.

Everything within the first act — and beginning of the second — builds up to The Ordeal, which is the first real conflict that the protagonist must face. The Ordeal is the midpoint of your story that works as a false climax, taking your protagonist to the depths of despair. It offers you the ability to create an engaging midpoint climax that takes you into the third act. It ups the stakes within your story by taking away beloved allies and mentors. And it sets up the necessary transformation that your protagonist must go through in order to prevail.

And after your hero has gone through all of that, you may want or need to reward them with something that they can use to take on the final threat they face during the climax of your story.

The Reward offers the protagonist the added boost they need to propel themselves through the conflict they face during the climax of the story where they are facing their toughest challenge — be it physical or emotional. A special weapon, an elixir, some knowledge, an experience, or reconciliation are the five types of rewards that heroes need to prevail.

Once they've attained the Reward, it's time for the hero to get on The Road Back to their Ordinary World. The Road Back allows the hero — and the reader and audience — to see the light at the end of the tunnel, if not for a few brief moments. It then introduces more conflict, higher stakes, and reveals everything that is at risk going into the climax of the protagonist's journey.

And the climax of your hero's journey encompasses The Resurrection stage.

But what does that stage entail, and what does it have to do with your hero's resurrection?

It Begins with the Highest of Stakes

If you've employed The Road Back stage of the Hero's Journey within your story, you've done the necessary work to set up the high stakes. And make no mistake, the climax of your story has to have your protagonist dealing with the highest stakes they've ever experienced.

It's the big fight, the final showdown, the emotional confrontation — everything that your protagonist has been preparing for throughout their entire journey has led up to this final moment or sequence.

In Star Wars, It's the Battle of Yavin. If the Rebels don't destroy the Death Star, their hidden base will be destroyed, and the Galactic Empire will rule the galaxy unchallenged.

https://youtu.be/2WBG2rJZGW8

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, it's Indy trying to stop the Nazis, realizing he can't do so single-handily, and then witnessing the opening of the Ark of the Covenant and the dire results. If the Nazis aren't stopped, they'll use the power of the Ark to take over the world.

In Rocky, it's the final rounds of the fight. If Rocky doesn't go the distance, he'll just continue being another bum on the streets.

In Field of Dreams, it's Ray meeting his father and learning that his whole journey was to reunite with him — "If you build it, he will come."

Your protagonists have to face the ultimate emotional or physical (preferably both) challenge. The higher the stakes, the better the ending.

Hero Resurrected

The best type of stories showcases a character arc that culminates to a real transformation. If you follow the stages of the Hero's Journey within your story, there's a reason that we show the protagonist in their Ordinary World to start — we need to see the beginning of their arc.

If we don't see Luke Skywalker as a naive dreamer of a farm boy, we can't experience a character arc with him as he later destroys the Death Star.

In The Karate Kid, if we don't see the angry, resentful, and weak Daniel from New Jersey, we won't feel an empathetic connection with the young man that faces his bullies and fears.

The climax stage of Campbell and Vogler's structure is the ultimate culmination of what the hero has learned and been through. We need to see the hero resurrected in this final act. Gone is the character we met in the Ordinary World. Now we must see them apply what they've learned through their many tests and conflicts.

And this climax begins with that resurrection, whether it be physical or emotional.

When Daniel goes down during his semifinal fight, there's a moment where he and his allies (Ali, his mother, and Mr. Miyagi) believe that his journey is over — that he has done all that he can to prove himself.

When Daniel shares his feelings about balance, Mr. Miyago realizes that Daniel must be given a chance to fight in the final bout against Johnny. It's less about Daniel's revenge and more about him being able to attain the balance he seeks in life. And that is when Daniel is given the reward of resurrection.

Luke Skywalker is resurrected as a Rebel pilot and hero.

Rocky is resurrected as a boxer who went the distance with the champ. He's no longer a bum.

Indiana Jones is a treasure hunter resurrected as an artifact attainer that respects the mysticism that he once scoffed at.

Ray is resurrected as a man who has finally seen life through his father's eyes, forgiving him.

The climax of your story is where the character arc comes to its end. They aren't the same person they were when they were in their Ordinary World, and they'll be forever affected by the journey they've been on.

Catharsis Is Key

Cinematic catharsis is the feeling we feel after the resolution of the story and the protagonist’s overall journey.

You've experienced it when you've watched a movie or read a screenplay that stayed with you afterward — when you walked out of the theater or closed that script and felt truly changed or affected somehow.

That’s the magic of a fantastic story, leaving the reader and audience truly touched, affected, and sometimes changed — catharsis.

It's the final moment in Field of Dreams where Ray has a catch with his father.

It's the end of The Pursuit of Happyness, where we witness Chris manage to see his own dream come true.

It's the moving scene in Dead Poets Society where Keating's students decide to act on the inspiration that Keating once supplied for them, while also giving him the justice that he deserved.

It's the moment when Daniel defeats Johnny and is finally embraced by everyone around him. Even Johnny hands him the trophy.

If you can inject your climax — The Resurrection — with cathartic emotional connections, you can close your story with an emotional bang that stays with us as we close that script or walk out of that theater.

It's not just about defeating the villain, winning the big game, getting the girl or guy, or accomplishing a goal. Your hero needs to be transformed by the end of the story. They need to be resurrected as a better version of themselves after having endured this long journey full of tests, obstacles, and hurdles. And their final test in this climax needs to be the ultimate challenge with the highest of stakes.

That's how you end your script with a bang — both physically and emotionally, as far as whatever the story and genre may be.

And remember...

"The Hero's Journey is a skeleton framework that should be fleshed out with the details of and surprises of the individual story. The structure should not call attention to itself, nor should it be followed too precisely. The order of the stages is only one of many possible variations. The stages can be deleted, added to, and drastically shuffled without losing any of their power." — Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers

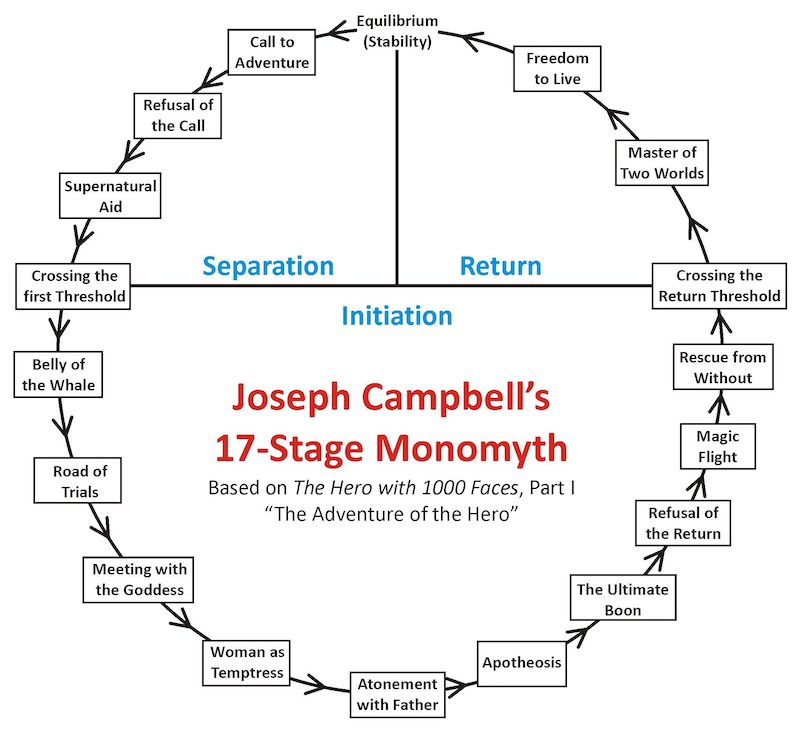

Joseph Campbell's 17-stage Monomyth was conceptualized over the course of Campbell's own text, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and then later in the 1980s through two documentaries, one of which introduced the term The Hero's Journey.

The first documentary, 1987's The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was released with an accompanying book entitled The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work.

The second documentary was released in 1988 and consisted of Bill Moyers' series of interviews with Campbell, accompanied by the companion book The Power of Myth.

Christopher Vogler was a Hollywood development executive and screenwriter working for Disney when he took his passion for Joseph Campbell's story monolith and developed it into a seven-page company memo for the company's development department and incoming screenwriters.

The memo, entitled A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was later developed by Vogler into The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters in 1992. He then elaborated on those concepts for the book The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

Christopher Vogler's approach to Campbell's structure broke the mythical story structure into twelve stages. We define the stages in our own simplified interpretations:

- The Ordinary World: We see the hero's normal life at the start of the story before the adventure begins.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is faced with an event, conflict, problem, or challenge that makes them begin their adventure.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero initially refuses the adventure because of hesitation, fears, insecurity, or any other number of issues.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor that can give them advice, wisdom, information, or items that ready them for the journey ahead.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their ordinary world for the first time and crosses the threshold into adventure.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero learns the rules of the new world and endures tests, meets friends, and comes face-to-face with enemies.

- The Approach: The initial plan to take on the central conflict begins, but setbacks occur that cause the hero to try a new approach or adopt new ideas.

- The Ordeal: Things go wrong and added conflict is introduced. The hero experiences more difficult hurdles and obstacles, some of which may lead to a life crisis.

- The Reward: After surviving The Ordeal, the hero seizes the sword — a reward that they've earned that allows them to take on the biggest conflict. It may be a physical item or piece of knowledge or wisdom that will help them persevere.

- The Road Back: The hero sees the light at the end of the tunnel, but they are about to face even more tests and challenges.

- The Resurrection: The climax. The hero faces a final test, using everything they have learned to take on the conflict once and for all.

- The Return: The hero brings their knowledge or the "elixir" back to the ordinary world.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!