Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey Part 9: The Reward

We dive into this archetypal story concept according to Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey and Christopher Vogler's interpreted twelve stages of that journey within his book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

Welcome to Part 9 of our 12-part series ScreenCraft’s Exploring the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey, where we go into depth about each of the twelve stages and how your screenplays could benefit from them. Before we dive in, here's a free download for you to catch up on all 12 stages of the hero's journey:

The first stage — The Ordinary World — happens to be one of the most essential elements of any story, even ones that don't follow the twelve-stage structure to a tee.

Showing your protagonist within their Ordinary World at the beginning of your story offers you the ability to showcase how much the core conflict they face rocks their world. And it allows you to foreshadow and create the necessary elements of empathy and catharsis that your story needs.

The next stage is the Call to Adventure. Giving your story's protagonist a Call to Adventure introduces the core concept of your story, dictates the genre your story is being told in and helps to begin the process of character development that every great story needs.

When your character refuses the Call to Adventure, it allows you to create instant tension and conflict within the opening pages and first act of your story. It also gives you the chance to amp-up the risks and stakes involved, which, in turn, engages the reader or audience even more. And it also manages to help you develop a protagonist with more depth that can help to create empathy for them.

Along the way, your protagonist — and screenplay — may need a mentor. Meeting the Mentor offers the protagonist someone that can guide them through their journey with wisdom, support, and even physical items. Beyond that, they help you to offer empathetic relationships within your story, as well as ways to introduce themes, story elements, and exposition to the reader and audience.

At some point at the end of the first act, your story may showcase a moment where your protagonist needs to cross the threshold between their Ordinary World and the Special World they will be experiencing as their inner or outer journey begins. Such a moment shifts everything from the first act to the second, allowing the reader and audience to feel that shift so they can prepare for the journey to come.

It showcases the difference between the protagonist's Ordinary World and the Special World to come. And, even more important, we're introduced to the first shift in the character arc of the protagonist as they decide to venture out into the unknown.

And it's within this unknown that the protagonist faces many tests and meets their allies and enemies — all of which define the meat of your story by introducing the conflict, expanding the cast of characters, and offering a more engaging and compelling narrative.

Once you've put your protagonist through those tests and once they've met their allies and enemies, they're going to need to Approach the Inmost Cave of the story — preparing to face their greatest fears and conflicts. This is an essential element of your narrative, allowing the reader, audience, and characters to catch their breath, reflect, review, and plan ahead for the conflict just over the horizon. And it allows you, the writer, to build the necessary tension and anticipation that you need going into the midpoint of your story.

Everything within the first act — and beginning of the second — builds up to The Ordeal, which is the first real conflict that the protagonist must face. The Ordeal is the midpoint of your story that works as a false climax, taking your protagonist to the depths of despair. It offers you the ability to create an engaging midpoint climax that takes you into the third act. It ups the stakes within your story by taking away beloved allies and mentors. And it sets up the necessary transformation that your protagonist must go through in order to prevail.

And after your hero has gone through all of that, you may want or need to reward them with something that they can use to take on the final threat they face during the climax of your story.

Here are the five types of rewards that your protagonist may need to prevail at the end of their journey.

1. Special Weapon

If you're writing in the action, science fiction, thriller, or fantasy genres, your character may need a special weapon — which Joseph Campbell referred to as "The Sword" — to defeat their greatest conflict.

This physical manifestation of The Reward can also be used in other genres, but it's far more prevalent in ones that involve action and adventure.

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and her friends escape the Witch's Castle with the Witch's broomstick — as well as the ruby slippers — which are essential to getting Dorothy back home.

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, The Reward is often one of the Infinite Stones. In Doctor Strange, Strange uses the Time Stone to reverse time and save Wong. He then enters the Dark Dimension and creates a time loop around himself and Dormammu. After repeatedly killing Strange to no avail, Dormammu finally gives in to Strange's demand that he leave Earth and take Kaecilius and his zealots with him in return for Strange breaking the loop.

https://youtu.be/tZyUxqBvMBE

In Thor, Thor earns the right to wield Mjölnir, his mighty hammer, once again after proving that he's worthy. The hammer returns to him, restoring his powers and enabling him to defeat the Destroyer.

https://youtu.be/jGKj70L5jrI

It could be a weapon, a magical treasure, or some type of device that helps your protagonist conquer the ultimate threat in the climax of your story.

2. An Elixir

An elixir is a magical or medicinal potion that can heal a wounded ally or land. During the peak of a story, the hero and their allies usually find themselves in peril — their lowest of lows. An elixir can be something that heals them enough to prevail in the end.

In Willow, Willow escapes the wrath of Bavmorda's power when Raziel has him use a protective spell that keeps him safe from turning into a pig. Willow later manages to return (heal) Raziel from the curse, allowing her to use her powers to remove Bavmorda's spell from the army.

In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, an elixir is used in the form of The Holy Grail to heal Indy's father, saving him from death.

In Mission: Impossible 2, Ethan Hunt gets the Bellerophon canister to Nyah in time to cure her of the virus she's been injected with, just as he kills Ambrose.

The elixir can work in fantasy movies, thrillers, or even medical dramas.

3. Knowledge

Knowledge is often mightier than any sword. It can be a fantastic tool to acquire to defeat a foe. It can drive a protagonist's internal need to succeed. It can inform them of the information they require to solve a final riddle or devise a certain plan of attack.

In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia, and Han Solo escape with the plans to the Death Star, which is a key component to the Rebellion defeating Darth Vader and the Galactic Empire. Without that reward after The Ordeal of the story (the escape from the Death Star), the Rebellion would not have the knowledge or perspective to destroy the Death Star. While the plans of the Death Star were physical, it was the knowledge within R2-D2 that helped the Rebellion succeed.

In Highlander, Connor's reward is learning that the Kurgan raped his long-departed wife. This knowledge gives Connor the extra desire and drive to defeat the all-powerful Kurgan.

In Top Gun, Maverick learns the truth about his late father's classified mission details from Viper. He's told that his father didn't make the mistakes others had said. In fact, his father was a hero that saved many lives and showcased some of the best flying that Viper has ever seen. This knowledge gives Maverick what he needs to graduate with his Top Gun class and gets past the loss of Goose as he takes on more MiGs in the climax.

Knowledge is power.

4. Experience

Sometimes protagonists have to experience an event or moment that opens their eyes and gives them the confidence that they need to prevail.

In The Matrix, Neo is ambushed and shot to death by Agent Smith. It's not until his resurrection that he can finally believe that he is The One that Morpheus prophesized. When Neo comes back to life and experiences that type of awakening, it's only then that he's able to manipulate the Matrix and defeat Agent Smith.

This reward works very well in dramatic stories as well. Your protagonist can be awakened by a near-death experience, surviving an overdose, or coming to some sort of realization about their life and situation. In character-piece stories that can't or shouldn't incorporate weapons, potions, or plot-driven knowledge, an awakening experience can be a vital reward within a dramatic hero's journey.

5. Reconciliation

When a protagonist reconciles with a love interest — as we see so often in romantic comedies and love stories — that reward can help them to conquer any emotional conflict that they've been facing. This reward is yet another outstanding option for dramatic stories, but it can also work within genre flicks as well.

In Return of the Jedi, Luke Skywalker reconciles with Darth Vader, which allows Vader's true self to surface as Anakin Skywalker.

In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indy is given a second reward that allows him to survive his biggest conflict — the reconciliation of his relationship with his father. It's evident in their conversation within the zeppelin and solidified when his father calls Indy by his preferred name — Indiana — telling him that his father's obsession with the Holy Grail isn't as important as their father/son relationship.

The Reward offers the protagonist the added boost they need to propel themselves through the conflict they face during the climax of the story where they are facing their toughest challenge — be it physical or emotional. A special weapon, an elixir, some knowledge, an experience, or reconciliation are the five types of rewards that heroes need to prevail.

And remember...

"The Hero's Journey is a skeleton framework that should be fleshed out with the details of and surprises of the individual story. The structure should not call attention to itself, nor should it be followed too precisely. The order of the stages is only one of many possible variations. The stages can be deleted, added to, and drastically shuffled without losing any of their power." — Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers

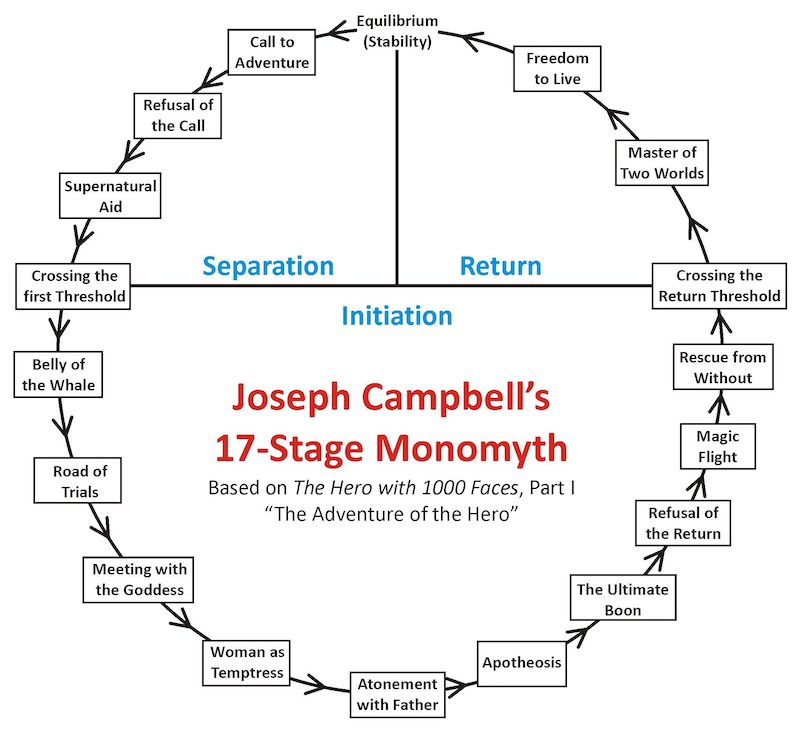

Joseph Campbell's 17-stage Monomyth was conceptualized over the course of Campbell's own text, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and then later in the 1980s through two documentaries, one of which introduced the term The Hero's Journey.

The first documentary, 1987's The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was released with an accompanying book entitled The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work.

The second documentary was released in 1988 and consisted of Bill Moyers' series of interviews with Campbell, accompanied by the companion book The Power of Myth.

Christopher Vogler was a Hollywood development executive and screenwriter working for Disney when he took his passion for Joseph Campbell's story monolith and developed it into a seven-page company memo for the company's development department and incoming screenwriters.

The memo, entitled A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was later developed by Vogler into The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters in 1992. He then elaborated on those concepts for the book The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

Christopher Vogler's approach to Campbell's structure broke the mythical story structure into twelve stages. We define the stages in our own simplified interpretations:

- The Ordinary World: We see the hero's normal life at the start of the story before the adventure begins.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is faced with an event, conflict, problem, or challenge that makes them begin their adventure.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero initially refuses the adventure because of hesitation, fears, insecurity, or any other number of issues.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor that can give them advice, wisdom, information, or items that ready them for the journey ahead.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their ordinary world for the first time and crosses the threshold into adventure.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero learns the rules of the new world and endures tests, meets friends, and comes face-to-face with enemies.

- The Approach: The initial plan to take on the central conflict begins, but setbacks occur that cause the hero to try a new approach or adopt new ideas.

- The Ordeal: Things go wrong and added conflict is introduced. The hero experiences more difficult hurdles and obstacles, some of which may lead to a life crisis.

- The Reward: After surviving The Ordeal, the hero seizes the sword — a reward that they've earned that allows them to take on the biggest conflict. It may be a physical item or piece of knowledge or wisdom that will help them persevere.

- The Road Back: The hero sees the light at the end of the tunnel, but they are about to face even more tests and challenges.

- The Resurrection: The climax. The hero faces a final test, using everything they have learned to take on the conflict once and for all.

- The Return: The hero brings their knowledge or the "elixir" back to the ordinary world.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!