The Differences Between Screenwriting Rules, Guidelines, and Expectations

What are the differences between screenwriting rules, industry guidelines, and Hollywood's expectations when it comes to your screenplays?

Visit any Reddit thread, comment section, or social media thread of a screenwriting topic or article, and you'll witness much debate when it comes to any form of screenwriting advice that is offered or questioned.

It's important to know the difference between these three types of screenwriting advice so that you, the screenwriter, can navigate through the Hollywood labyrinth with the best compass possible.

Here we offer simple breakdowns of the rules, the guidelines, and the expectations when it comes to your screenwriting and the screenplays you try to use as calling cards to make your screenwriting dreams come true.

Screenwriting Rules

By definition, a rule is one of a set of explicit or understood regulations or principles governing conduct within a particular activity or sphere.

Rules are set in stone, and while they can be bent, they usually should never be broken.

When it comes to screenwriting rules, we have to look directly at objective elements like format. There's a reason for the universal format that we know and "love" today. It evolved from the theatre stage plays, the early days of cinema when screenplays were referred to as scenarios, and into the 21st century when filmmaking changed due to technology and the growth of the industry.

The most basic screenwriting rule is script format.

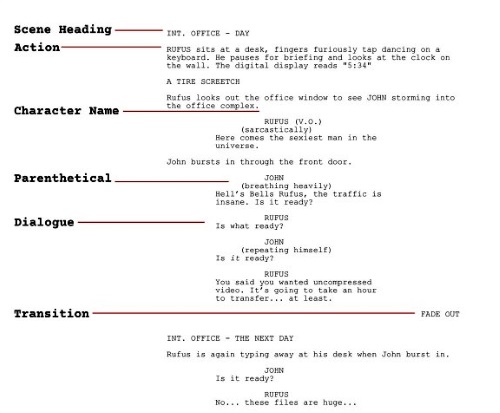

The Master Scene Format has six main elements:

- Scene Heading

- Action

- Character Name

- Parentheticals

- Dialogue

- Transitions

These elements are the essential screenwriting rules that every screenwriter must follow.

Scene Headings need to communicate whether the scene is an interior (INT.) or exterior (EXT.). Following that, a location has to be selected. Lastly, the heading needs to designate whether the scene takes place during natural sunlight hours (DAY) or after the sun has set and night (NIGHT) has fallen.

Remember that a screenplay is a technical document that hundreds of people, sometimes thousands, are tasked with interpreting through their own department's needs. This essential information of INT or EXT, LOCATION, and DAY or NIGHT is required to both visualize the film and make that cinematic story come to life as written.

This format is a rule that can't be broken by any means. It certainly can be bent with the use of variations of DAY and NIGHT (DUSK, DAWN, MORNING), but only when necessary to communicate a more specific absence or excess of light.

Once written — either on assignment or through acquisition — the script is given to various technical and creative departments. It will be broken down by location, interior shots, exterior shots, night shots, and day shots. All of which will dictate shooting schedules, construction schedules, production needs, and budgets.

Equally important is the format that extends to scene description (action), character names, parentheticals, dialogue, and transitions. All of these elements need to be formatted in simple-fashion to communicate the visual and audio aspects of the screenplay so the script reader, producer, director, cast, and crew can visualize the script as a cinematic experience. If there was no universal format, that visualization of the screenplay would be much more difficult to comprehend.

In the context of the script reader, this format allows their mind to log that vital information to apply to the open canvas of their mind as they visualize the script.

"Okay, we're inside (INT.) a building (LOCATION). It's dark — there's no light coming in from the windows (NIGHT)."

The scene description (action) is written in the present tense to more easily convey the concept that these events are happening right now (in the mind's eye of the script reader). The character name tells us who is saying the dialogue while parentheticals can be used to offer added information of action or emotion that is attached to the words being spoken. And finally, transitions (DISSOLVE TO, SMASH CUT TO) can be used to convey a sense of visual style within the script.

So it's easy to see that format is the sole screenwriting rule. It serves a fundamental purpose and screenwriters need to do their best to keep that format consistent and straightforward.

Guidelines

"Wait, we're already to guidelines?! What about all of the other screenwriting rules?"

The fact is, no matter what any successful screenwriter, producer, executive, filmmaker, agent, manager, or guru says, there are no rules beyond format. For every "rule" that they dictate, plenty of scripts can be read to the contrary.

This is where we get into the guidelines of the industry.

Synonyms to the word guideline include recommendation, suggestion, and advice.

If you've watched enough movies — and especially if you've worked in the film industry long enough — you begin to understand that there are some aspects of screenwriting that work and serve a particular purpose.

The professionals in the industry read more scripts than you likely ever will. They conceive them, develop them, pitch them, sell them, produce them, and release that final product to the masses. Because of all of this experience, there are specific guidelines to follow.

Having some type of specific story structure is a pretty strict guideline that many consider a rule — because without structure, it's difficult to portray a cinematic story within the confines of a two-hour running time (give or take half an hour or more). Where people make a mistake is dictating what type of structure should be used — as a rule.

The fact is, there are many different types of structures that screenwriters can choose from. All of which have been evident in acclaimed and successful films.

Read ScreenCraft's 10 Screenplay Structures That Screenwriters Can Use!

The guidelines of capturing the reader within the first five to ten pages are there as solid screenwriting advice meant to help get your script up the totem pole. If you take thirty pages to get to the central conflict of the script — which is basically the core concept — you're going to lose the interest of most of those script readers.

When it comes to how scene description is written, you often hear the phrase Less Is More. This is a specific guideline that many industry insiders suggest screenwriters utilize to get the visuals across as quickly as possible, so the pacing of the script is fast. When the pacing is fast, the script reader isn't caught up in the details of lengthy scene description. Instead, they are invested in the story and able to visualize it quickly as your movie plays within their mind's eye as quickly as reels of film releasing images onto a theater screen.

But there are certainly times when your scene description calls for a little more detail beyond the often-suggested one to two lines per scene description blocks. That's why the Less Is More phrase is a guideline.

Read ScreenCraft's Why Every Screenwriter Should Embrace “Less Is More”!

With dialogue, that Less Is More phrase applies as well, but for different reasons. Because cinema is a visual medium, stories are told primarily through action, reaction, and physical emotion. Dialogue is there to help tell those stories — we do live in a speaking world — but all too often, screenwriters use dialogue as a crutch to tell the story. This leads to another common screenwriting phrase — Show, Don't Tell.

So while the guideline for dialogue is to use as little of it as possible, there are obvious exceptions. Many great character-driven films use dialogue as a sort of cinematic poetry to convey inner emotions and conflict. Look no further than outstanding "talking head" movies like Before Sunrise, My Dinner with Andre, and The Big Chill.

But these films are a niche subgenre of sorts. Most of Hollywood wants screenwriters to show, not tell. So it's a guideline to follow, but certainly not in every case.

Read ScreenCraft's The Single Secret of Writing Great Dialogue!

Moving onto transitions, many will decry using them in screenplays. This is often mistaken as a hard rule. However, there are many exceptions.

Back in the earlier days of cinema, screenplay transitions were cues to the editing team to communicate how transitions between shots were to be handled.

CUT TO was a simple direction that stipulated the literal cut from one scene to another — usually, but not always, referring to a location change as well. In older scripts, you will often find such a transition between every new scene. Today, it's implied that we will CUT TO a different location and scene, so it's unnecessary to include that transition between every scene.

Variations to that transition began to appear as cinematic styles started to form. Artistic but technical transitions such as FADE IN, FADE OUT and DISSOLVE TO started to appear in scripts. The latter of which was a prevalent transition as films like Citizen Kane pushed the boundaries of art meeting the technology of film.

In the 21st century, we've seen a shift away from using such transitions in between scenes because screenwriters are advised not to direct the script — that's the director's job. However, there are instances where a screenwriter can use transitions to convey a point, a moment, or a specific visual that is partial to the story and how the script reader should visualize it.

Read ScreenCraft's Everything Screenwriters Need to Know About Transitions!

And then we look at the more prominent guidelines beyond format elements — story, pacing, characterization, theme, conflict, etc.

There are no set-in-stone rules for these screenplay elements, no matter what any individual "in the know" tells you.

Some scripts have less story than others. Some scripts embrace slow-burn pacing while others call for a fast pace atmosphere. Some characters have significant arcs while others don't (Indiana Jones). Some stories have more conflict than others.

The guidelines you find pertaining to these essential elements are less about being rules, and more about being food-for-thought. Certain genres require less or more of these elements.

A guideline is a recommendation, suggestion, or piece of advice often based on the knowledge and experience of those sharing it.

Expectations

Expectation has two interesting definitions:

- a strong belief that something will happen or be the case in the future.

- a belief that someone will or should achieve something.

When we talk about expectation, we're going beyond rules and guidelines. We're discussing an individual's wants and needs. That individual is generally either the person considering your screenplay — producer, executive, manager, or agent — or the member of the general audience sitting in the theater ready to watch your movie.

Let's talk about the industry insiders first.

When you write a screenplay under the umbrella of a certain genre, there are expectations. If you're writing a comedy, it has to be funny. If you're writing a horror movie, it has to be scary. If you're writing an action flick, it has to be full of action and adventure. If you're writing a drama, it has to be full of dramatic events and emotion.

When you're trying to market your script, your script has to live up to the expectations of the logline, which is generally the first thing about your script that industry insiders will read. If your script doesn't deliver on that concept and genre you've pitched, you're not meeting their expectations.

That's why you'll often read specific screenwriting advice that demands certain concept, story, and character elements for certain genre scripts. And when it comes to the companies considering your work, they often have a checklist that they need to mark to consider representing, acquiring or producing your screenplay.

Action scripts need to have a big action opening and many additional unique action sequences throughout the rest of the script.

Comedy scripts need to have a hilarious hook because that's how comedies are sold in Hollywood today.

Science Fiction scripts need to have an intriguing world or concept to stand apart from the rest.

We could go on and on with every genre and subgenre. The point is that there are certain expectations when it comes to each type of screenplay — expectations that industry insiders need to see come true to prove that your script is a viable investment.

You learn these expectations by researching the companies you plan to approach. You look at their titles and find out what types of movies they like to make and what kind of movies they clearly avoid. These are their expectations. You don't send a dramatic character-piece to Michael Bay's production company. And you don't send a space opera to specialty companies that focus on acquiring or producing indie character pieces.

And then we have the audience's expectations. This simply goes back to a comedy needing to be funny, an action script needing to be action-packed, a horror script needing to be full of scares, etc.

When the audience sees the trailer for your movie, they have immediate expectations that need to be met when the lights go down, and the movie starts.

So let's stop the endless tirades on social media, Reddit threads, and comment sections about this being a rule, that being a guideline, and those industry expectations that you can't escape.

The format is the rule. You have to abide by it. It can certainly be bent now and then, and there are slight variances that are acceptable, but the above breakdown is what you should stick to.

The guidelines of story, characterization, structure, page count, pacing, and others are there to help guide you through the process of telling your cinematic story in the most compelling, engaging, entertaining, and cathartic ways.

The expectations of the industry — and even the audience — are often inescapable and must be maneuvered with the understanding that it's a business for the industry and a service for the audience. And with that comes expectations that you often — but not always — have to meet.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!