How can you teach screenwriting to kids amidst a world of Fortnite, YouTube, texts, and Snapgrams?

There are millions of little potential Ephrons, Spielbergs, Codys, Tarantinos, Feys, Goldmans, and Rhimes out there — future heirs to the Hollywood thrones of screenwriting and cinematic narratives. But since their attention is largely focused on varying degrees of screens, it's difficult to launch their own imaginations.

Here we offer some easy steps to teaching kids about screenwriting and cinematic storytelling if you think they might want or need a creative outlet that falls in line with any possible movie and filmmaking passions.

Give Them a Plethora of Movie References

Watching movies is an essential education for any screenwriter young or old. Films provide an excellent frame of visual reference and inspiration. Unfortunately, many parents are hesitant to introduce cinematic narratives to their children — fearing that any sensitive story elements (language, fear, death, loss, peril, violent imagery, etc.) may scar them for life or push them to boundaries that parents don't want their children to go.

Storytelling is a very natural way to teach life lessons. The visual aspect of film and television offers children an instant portal into such life lessons as the story falls into place before their eyes.

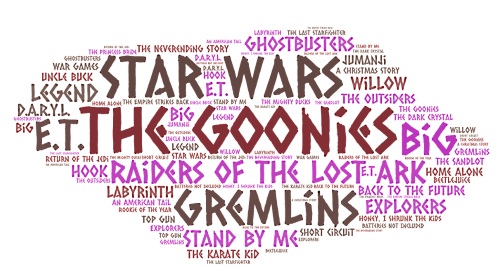

Back in the 1980s (and some of the 1990s), Hollywood didn't hold back as much. Language, fear, death, divorce, loss, peril, and even some violent imagery were staples among some of the best films geared towards the younger demographics in the PG category — as well as the later PG-13 rating —including the original Star Wars trilogy, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Gremlins, Stand By Me, Ghostbusters, Back to the Future, Big, Explorers, The Outsiders, and countless others.

Somewhere during the 1990s and into the 21st century, parents were asking for a more lighter fare. Animated movies became the sole source of viewing for children. While Pixar indeed introduced some more "adult" storytelling, most other animated films went for the easy laughs mixed in with pop culture references to satisfy the parents.

For your child to grasp cinematic narrative, they need to be able to reach beyond the comical hijinks of today's animated pictures, television shows, and funny YouTube videos.

Consider allowing your child the freedom to explore some of those classics mentioned above. If you fear for their safety and well-being, the best assurance that they'll be just fine is to open up a dialogue with them beforehand. Teach them that any scary, dangerous, or intense moments are nothing more than movie magic. Consider showing them the behind-the-scenes features found in DVDs and Blu-rays. Let them know that any inappropriate language or behavior they witness in a movie is not representative of how they should represent themselves and the family in public. Make it a life-teaching moment.

And beyond that, trust them.

Note: This is written by a father of two that introduced the very classics above very early on in their lives, just as he was raised on those movies (and many more R-rated ventures) by his own open-minded and trusting parents.

Introducing these types of films, as well as many others not mentioned above, will teach the kids the general screenwriting narrative. The more they watch, the more they will get a sense of pacing, tone, theme, structure, characterization, and style. And that will later translate into what they eventually write themselves.

Toys, Toys, Toys

The toy market boomed in the 1980s, thanks to now-classic lines from Star Wars, G.I. Joe, Transformers, He-Man, My Little Pony, and beyond. This was primarily before the advent of home gaming systems. Some of the best screenwriters in film and television came from this generation of kids that played endlessly with these toys as they structured their own adventures in the backyards, ditches, and bedrooms of the neighborhood.

These days, kids have their faces on screens constantly. They're on social media. They're texting. And the adventures they embark on are primarily presented to them through XBox, Playstation, and their devices.

While this generation plays Fortnite, prior generations grew up playing those very same adventures — but with real figures in their hands as they concocted stories and narratives using their own imaginations, as opposed to relying on excellent game design and graphics.

If your kids are still young, don't shy away from buying the figures and vehicles from some of their favorite movies.

Pixar's Cars franchise made over $2 billion in toy merchandising from the first film alone. Why? Because children could continue the adventures of those characters with their own two hands and some imagination.

You can even break out your old childhood toys and throw them into the mix.

Playing with physical figures and vehicles was the 1970s and 1980s generation's early education in storytelling. Some of the narratives created would go on for a whole summer. Beloved characters would die. They would find themselves on adventures and in peril.

These are the defining cinematic elements to screenwriting — concept, conflict, and characterization.

If they're not too old, get your kids in on the toy craze early — specifically ones that are attached to cinematic franchises that they can view and build narratives from. Even if your child isn't showing any early interest in cinematic storytelling, you're giving them a creative outlet that is otherwise dying away in these screen-obsessed times.

Have Them Think in Pictures

Screenwriting is a visual medium. We tell stories in pictures. We show rather than tell. This is the first true lesson in screenwriting for kids now that you've given them a visual frame of reference by allowing them to watch more movies.

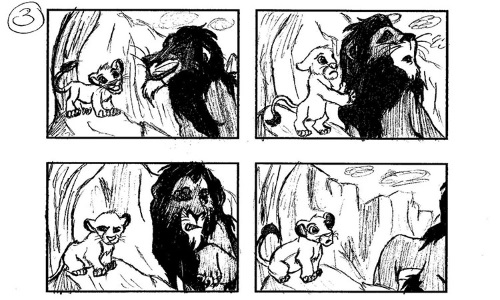

Storyboards are a fantastic way to teach screenwriting in that context. Each frame offers a visual moment, emotion, or action.

Perhaps the best display of this type of storytelling is through comics and graphic novels. Showing a child the panels within this visual medium teaches them the simplicity of telling a detailed story through pictures.

Yes, the speech balloons and captions offer literary content beyond the image, but the wonderful lesson within those balloons and captions is that it also teaches them about two additional elements of screenwriting — dialogue and scene description. Both are minimalistic, due to the lack of page real estate. Thus they teach children that dialogue and scene description can and should be short, sweet, and to the point.

You can even go the extra distance and do your research through Amazon, eBay, and your local comic store to find comic adaptations of their favorite movies. Then you have a specific visual reference to teach them how to think in pictures.

Beginning, Middle, and End

Now that they've seen how to tell stories with pictures — accompanied by brief dialogue and scene description as well — it's time to teach them how to apply that to a narrative.

The Three-Act Structure is the most basic form of storytelling on the planet. Every movie works from the structure of beginning, middle, and end, whether pundits want to admit to that or not.

A character and their world are introduced, a conflict arises, and they are forced to react. This structure has been around since the dawn of humans. Cave dwellings showcase simple stories with three etchings:

- Stick figure hunters with spears.

- A beast appearing amongst them.

- The beast lies dead with spears piercing its body.

Introduce this structure to your budding screenwriter.

You can have them start by drawing three panels — beginning, middle, and end. Instruct them to tell you a simple story through pictures. You can even say that they're writing a movie (albeit a short one).

After a few tries, give them an empty notebook where they can tell stories in pictures at their own leisure. You'll likely be shocked to open that notebook one day and find multiple stories — or one epic one.

The Screenwriting Basics

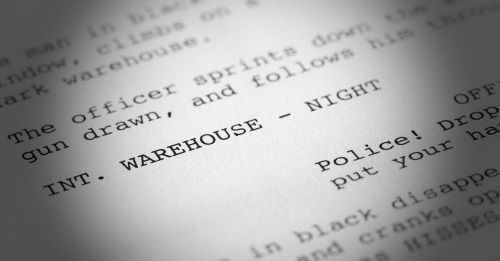

When you think they're ready — or wanting to take the next step — teach them the screenplay basics they need to get going. Remind them that for each scene, they have to first answer these three fundamental questions:

- "Is the scene outside or inside?"

- "Where is the scene taking place?"

- "Is it during the day or at night?"

When they answer those questions, you've just taught them how to write Scene Headings. You then instruct them to use INT. for interior scenes (inside), EXT. for exterior scenes (outside), list a specific place (building, house, forest, etc.), and then write DAY or NIGHT depending upon how they envision the scene.

After that, tell them to write down what is happening in the scene. Remind them to think in pictures and keep everything very brief, much like they saw in the comic panels you showed them.

You've just taught them how to write Scene Description.

And yes, you can show them the basics of dialogue format and, again, remind them to keep that element of their screenplay very brief as well. Just like the comic panels they read.

For a more specific breakdown of basic screenwriting format, Read ScreenCraft's Elements of Screenplay Formatting!

Get Them the Software

If you have it yourself, wonderful. If not and they've shown enough interest to want to take it to the next level — and make the formatting easier for them in the process — consider treating them to the latest screenwriting software.

Final Draft is the marquee product. WriterDuet is a viable alternative, and perfect for Chrome books or any other Wi-Fi device. Free versions of software like Celtx are available as well.

The wonderful thing about them using software is the simplification of the format to the point that they can go from Scene Heading, Scene Description, and Dialogue with the tap or click of two buttons. The other bells and whistles aren't necessary — until they're ready to explore the format further.

Get Them the Scripts

While viewing movies works well to give them visual references for inspiration, there's no better screenwriting education than reading screenplays. These days, you can Google the name of their favorite movies, along with the phrase screenplay PDF, and find a majority of their favorites online.

It's the best way to learn as long as you communicate to them that they should focus on those basics of Scene Headings, Scene Description, and Dialogue. Many screenplays showcase advanced formatting with various technical terms, transitions, and other elements that they aren't needed at this level.

And if they have questions, just be there to answer. And if you don't know the answer, it's just a few clicks away online.

An Advanced Training Lesson

The final step they need to take is to flex that screenwriting muscle a bit. An excellent lesson for any beginner is to watch a movie scene and attempt to translate it back into screenplay format using the basics they've learned.

They can utilize the software you've provided, or just keep a notebook of handwritten scenes.

That's all they need to write screenplays at this level.

You've given them movies to work as visual references and inspiration. You've given them physical figures and vehicles to allow their imagination to take hold as they create stories for them. You've given them comics and graphic novels to read as examples of telling stories in pictures with brief dialogue and description. You've given them the building blocks of all stories — the Three-Act Structure in the form of beginning, middle, and end. And you've given them the essential formatting tools necessary to tell that cinematic story.

The rest is up to the kids. The worst thing that you could is write something for them — as many parents are tempted to do their children's homework "right" or create projects with that added "parental touch."

Storytelling is in our DNA as humans. We've been telling stories since the beginning of humankind. It started in grunts and gestures — later over the village or tribe fires. It evolved in direct speech and language. It developed even more through artwork on cave walls. It advanced to the written word, documented in plays and books. And then it was transferred to the screens in visual magic.

The children of today are growing up with more than we ever did, in the context of visual storytelling. There is more content than we could have ever imagined decades ago — and more ways than ever to view it.

Screenwriting is in their blood — literally. All that parents and teachers can do is give them the tools and general knowledge they need. The rest is up to them and their imagination.

And then if you really want to take it to the next level, give them a camera.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!