Outlines, Treatments, and Scriptments, Oh My!

Most screenwriters have likely heard these terms — outlines, treatments, and scriptments — but many don't really know what they truly are, why they exist, and how they are supposed to be written and utilized. The very mention of them can be intimidating. Let's shine a little light on what these things are.

The Difference Between Outlines and Treatments

Let's start with the big two — outlines and treatments.

Screenplay outlines and treatments are the most common development tools used in Hollywood and beyond today. But they're often used for very different reasons.

Outlines

Outlines are often used by the screenwriter during their own development and writing process. They're meant to be read only by the writer — along with their writing collaborators, which can include writing partners, producers, directors, and even managers — as a means to collect visualization concepts that pertain to scenes, plot points, and story arcs.

However, they are more and more requested by production companies and networks (Hallmark, Lifetime) as well, where they read more like beat sheats.

They essentially act as early development blueprints for how the writer and their collaborators plan to assemble the scenes within a screenplay.

Outlines vary in size, shape, and form — depending upon the writer, as well as the needs of the possible producers, directors, and managers that they are working with during the developmental phase leading up to the actual writing of the script. The outline allows the writer to construct a general list of sequential scenes and moments in the order that they will be written within a screenplay.

This writing tool allows the writer to get an overview of the story beats and moments before applying them into the screenplay format of locations, scene description, and dialogue. Using this overview, you can make creative and editorial choices before you take the time to write those scenes and moments in their cinematic entirety. So if you find within that outline that certain scenes are redundant, repetitive, or unnecessary, you save the time of having to move, adjust, or delete those written scenes after you've already taken the time to write them.

This tool is especially essential when you're working with writing partners, or producers, directors, and managers that may be part of the development process. As a professional screenwriter under assignment, producers and directors will especially have some creative input into how the script's story is constructed.

This, of course, will change project-to-project. Some producers will let you have your first draft and then work with you on the second once that first is handed in. Others will want to have input into where certain scenes, sequences, and story beats are present within the eventual first draft. If directors are already attached, they'll likely want to have their say as well.

Manager input is usually given when the screenwriter is writing a script on spec (writing something before it's been optioned or sold). Some managers want more input than others, but their collaboration is sometimes key because they know what their Hollywood contacts respond to or not.

And yes, writers writing on spec without any representation can use outlines for the same purpose of organizing one's thoughts and visuals.

Treatments are meant to be read by others outside of the creative process as a means to convince the powers that be to either consider a screenplay in question for acquisition and production or to help them understand the vision that the screenwriter has for a possible writing assignment.

These documents vary in length — depending upon the needs and wants of studio executives, producers, agents, and managers — and cover the more specifics of the story, utilizing prose in the forms of descriptive paragraphs that tell the story from beginning to end with all of the plot points, twists, turns, revelations, and character descriptions, but void of any dialogue (exceptions are sometimes made on that front).

Where a synopsis would generally cover the broad strokes of the story within three paragraphs and one page, treatments cover every detail of story and character so that those reading it will be able to get an idea of what movie they are considering to make.

The eventual screenplay will have the stylistic delivery of the story pitched within the treatment, complete with character dialogue, scene description, creative editing and visualization delivery, etc.

Treatments, in these contemporary times, are also formatted as a sales pitch, beyond just the telling of the story. You can include elements like a general overview — which details the genre and type of story — as well as character breakdowns and setups.

Read ScreenCraft's How to Sell Your TV Series the Stranger Things Way!

So What's the Difference?

As you can see, to put it simply, outlines are meant for the writers while treatments are meant for those in the position of acquiring and producing the eventual screenplays that have been written or may be written.

Writers will use outlines — with or without feedback from collaborators — to prepare to write the screenplay.

Studio executives, producers, and potential representation will use treatments to decide if they are interested in the eventual screenplays that they'll read or hire someone to write.

So How Do You Write Outlines and Treatments?

As mentioned before, outlines vary per writer and situation.

They can often take the place of the old school tactic of using index cards to organize where scenes are placed within a screenplay. Writers use index cards by writing down basic scene headings — along with a brief sentence or fragment of what is happening in the scene — and numbering them in order of the appearance they'll have within the script.

Outlines work the same way, but you can use the easier method of creating a bullet point or numbered list.

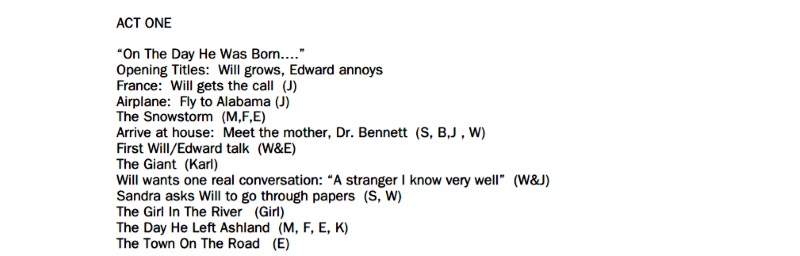

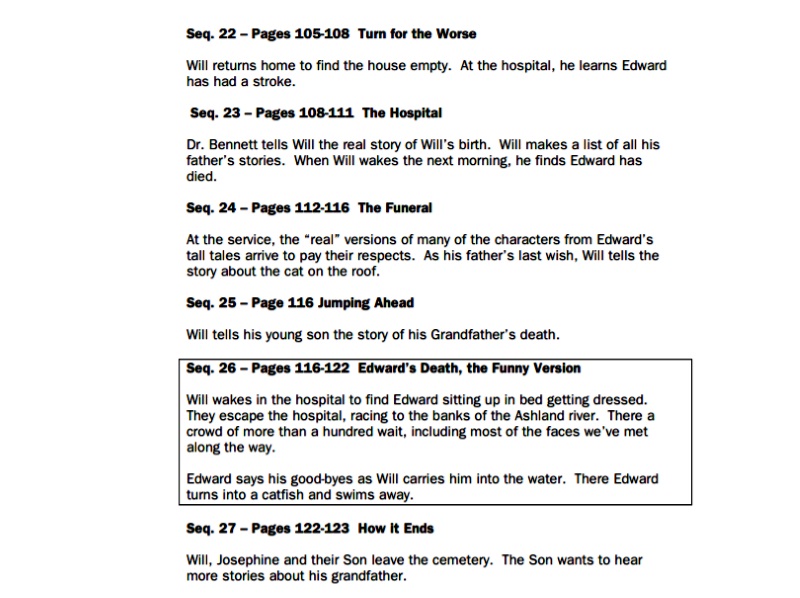

Here is an example that Hollywood screenwriter John August shared on his podcast site. The script he was developing was Tim Burton's Big Fish.

As you can clearly see, this outline is formatted in a way that is specific to the writer's needs only. August knew the detail of each scene but used simple notes to organize them.

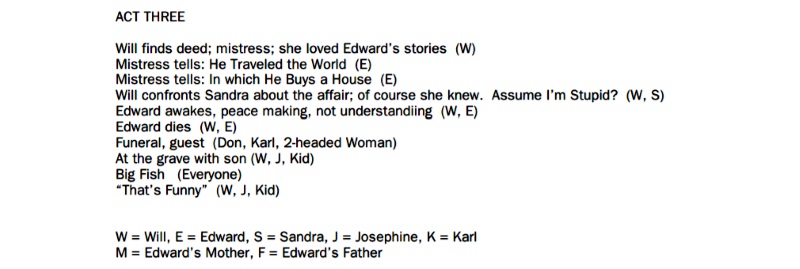

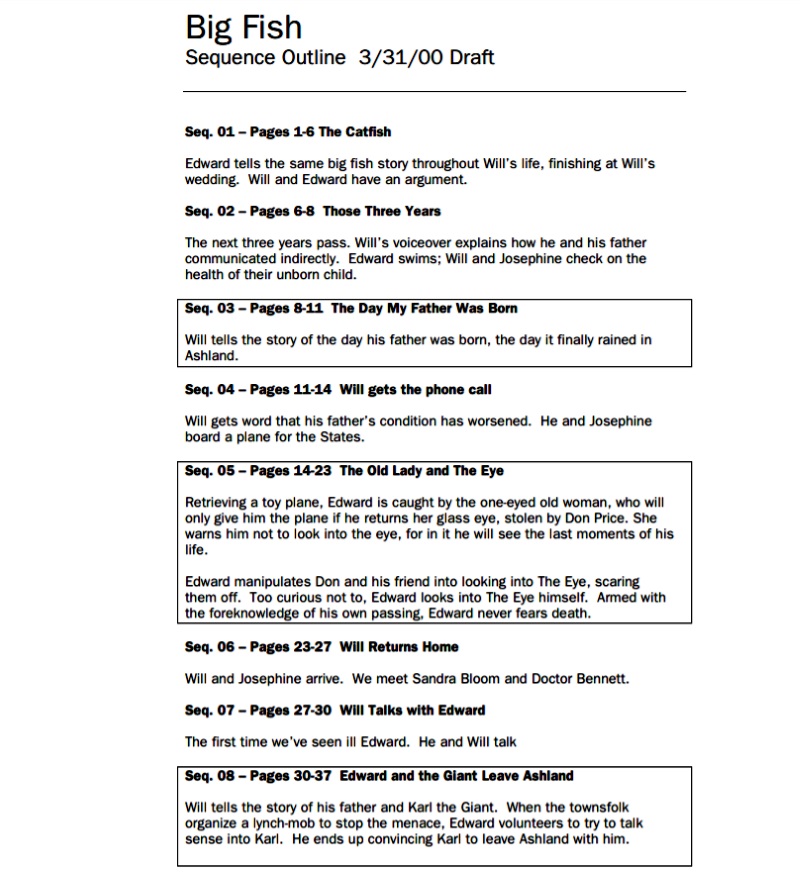

He then offers a more specific outline after the first draft of the screenplay was written. He likely used this for his collaboration with Burton, and perhaps the producer. You could use this type of format — minus the page numbers — as an outline that offers slightly more detail if needed.

As you can see, outlines are all about organizing the core of each and every scene and moment within a screenplay — whereas treatments add additional layers using prose and longer paragraphs as you "tell" the whole, complete story to someone else.

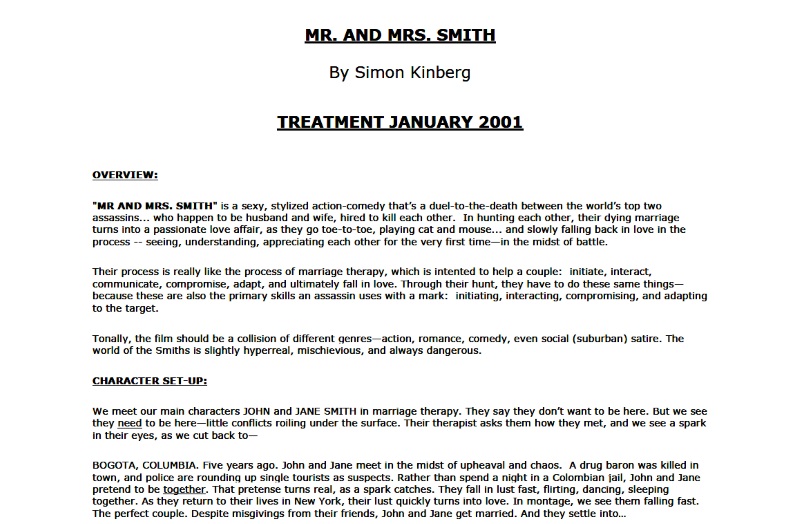

Hollywood screenwriter Simon Kindberg shared the treatment for his eventual action hit Mr. and Mrs. Smith over at Creative Screenwriting Magazine.

And the treatment continues on for a total of just four pages. CLICK HERE to read the full treatment. It offers an overview, which touches on the genre, the characters, their relationship, and the story. Some treatments can be as long as 7-10 pages, or upwards of many more. Generally, you want to keep it as short as possible while still offering the necessary length to tell the whole story from beginning to end.

You'll notice that no dialogue or scene headings are utilized within this treatment. However, you can include such elements to create a more stylized reading experience for those studio executives, producers, and potential representation. Enter the scriptment.

Developing a Series Bible? Submit to the 2020 ScreenCraft Pilot Launch here.

What the Heck Is a Scriptment?

Scriptments are hybrids of treatments and screenplays. If you'd like to create that more entertaining and visual treatment, you can incorporate screenplay format and prose to showcase some of the bigger moments within the treatment — thus creating the hybrid some refer to as a scriptment. The usage of the term is often attributed to James Cameron, who had always written what he called "scriptments" for various projects of his, including The Terminator, Strange Days, Titanic, Avatar, as well as for his initial Spider-Man pitch when he was briefly attached to the project back in 1996.

Scriptments still tell the story from beginning to end like treatments, but they often contain slug lines — INT/EXT - LOCATION - DAY/NIGHT — and even use screenplay formatted character names and dialogue.

Because of this added format, the pages will be longer in certain sections, adding to the overall length of what would normally be a treatment.

Keep in mind that a scriptment is not a screenplay. Most of the writing is in treatment prose using paragraphs to explain the story and summarize what the characters are saying. The screenplay format elements of character names and dialogue are only used sparingly to feature the major moments within the story.

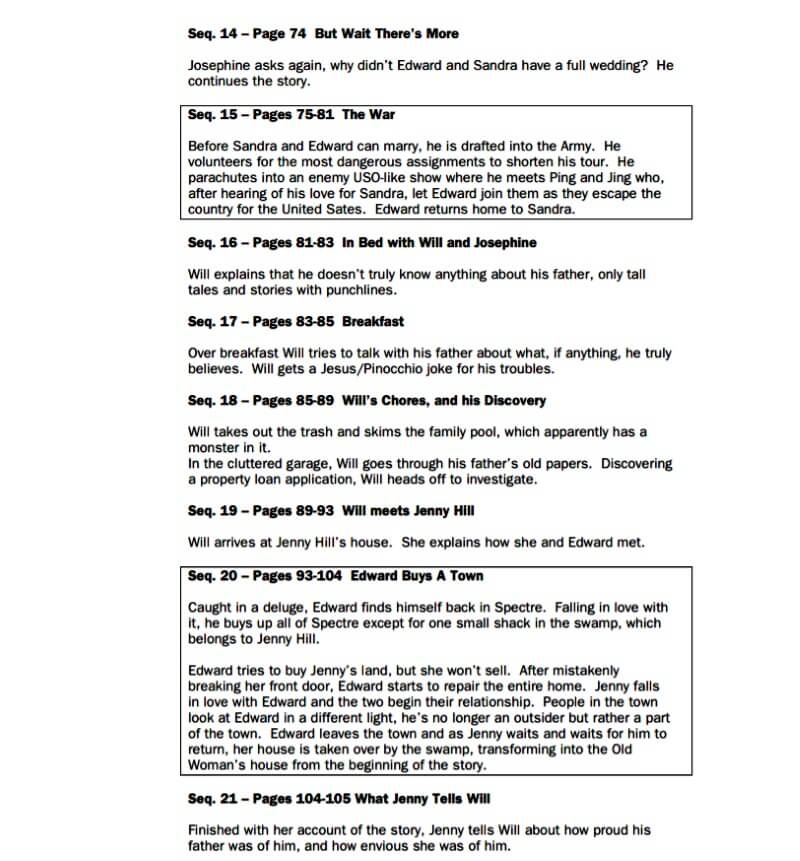

Below is an excerpt from James Cameron's scriptment for 2009's Avatar. You can read an early version of the whole scriptment HERE.

![]()

Do I Really Need to Write Outlines, Treatments, or Scriptments?

Outlines are up to you and your collaborative team. If you're writing on spec on your own, outlines can be a handy tool to prepare yourself for the actual writing process — organizing your thoughts and allowing you to budget your writing time. However, they can also be a hindrance, causing you to over-analyze your story and risk the loss of creative freedom.

Read ScreenCraft's 3 Ways Screenwriters Can Avoid the Paralysis of Analysis!

Use outlines if you think you need them. And if you think you need them, just be sure to leave a little room for discovery during your creative writing process.

Treatments and scriptments are necessary only when the powers that be request them. You can't sell a project from a treatment alone, so don't kid yourself into thinking that either of these documents are shortcuts to actually writing the script.

They are more prevalent in the development process while you're writing on assignment. Producers and development executives will give you the concept they wish for you to write, and you'll likely be asked to write a treatment or scriptment — the two are actually one in the same, albeit with slightly enhanced format in regards to the scriptment — to either pitch your take on the proposed assignment or just communicate how you intend to write it so they can offer their notes before you go to script.

When you're writing on spec and marketing your scripts, you really don't need to write treatments or scriptments as a selling tool. Producers, executives, agencies, and management companies have plenty of interns, assistants, and junior executives to read your script and write script coverage that includes summaries of the story. You may stumble upon a company or individual here and there that still prefer to read treatments from writers, but they are few and far between.

Outlines, treatments, and scriptments are tools that the film and television industries have used for decades — with varying degrees of necessity and demand.

Outlines are for the writer and their respective creative team, if any. The format that is used and the amount of detail that you put into an outline is up to you, the screenwriter.

Treatments and scriptments are for those at the other end of the table. They are prevalent enough that the Writers Guild of America has negotiated them into the guild's basic agreement. Guild signatory companies are required to pay minimums of around $35,000 for a treatment that you write on assignment and around $53,000 for original treatments based on your original idea. This doesn't stop some companies from requesting you to voluntarily write a treatment for a screenplay that you are trying to market to them on spec — but as we mentioned earlier, this happens few and far between these days.

That said, it doesn't hurt to know how to write them. And now you hopefully have a better idea of how to go about doing that. Keep writing.

For more information on developing your treatment or series bible, check out "How to Create the Perfect Show Bible."

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!