Screenwriting Basics: How to Write Cinematic Fight Scenes

How do you write a cinematic fight sequence within a screenplay that engages the reader and avoids the traps and temptations of writing blow-by-blow descriptions — which often force those readers to skim and lose interest? We're going to explore that question here for this installment of our ongoing Screenwriting Basics series.

Cinematic fight scenes can be a quandary for screenwriters. We know not to be too specific in scene descriptions to avoid wasting precious screenplay real estate, and we also know not to take on a director's job with specific shot descriptions.

But how do you write a story that features fight sequences pivotal to the dramatic arc of the story without boring the reader to death with the details?

Cinematic Fight Scenes Should Be About Drama, Not Action

We know, that sounds like an oxymoron, but it's true.

The greatest and most memorable fight sequences throughout the history of movies are remembered not because of specific fighting techniques, kicks, and punches — it's about the drama that composes the subtext of those sequences.

Look no further than the success of the Rocky franchise.

In the original Rocky, the end fight sequence was a result of the masterful build-up that screenwriter Sylvester Stallone crafted. Rocky divulges his inner thoughts to Adrian the night before the fight.

We learn that he knows he can't beat Apollo Creed — that he's not even in that champ's league. But then Rocky says something that sets the course for the iconic fight we are about to see. He says something that injects the drama that will drive that fight sequence we all know and love.

"It really don't matter if I lose this fight. It really don't matter if this guy opens my head again. Cause all I want to do is go the distance. Nobody's ever gone the distance with Creed. And if I can go that distance, seeing that bell rings and I'm still standing, I'm going to know for the first time in my life, that I weren't just another bum from the neighborhood."

For most great fight scenes, it's about finding the drama within the fight. What are the stakes? It can't be just about who is tougher or more skilled. You have to set the stage for the fight by showcasing both the physical and emotional stakes at hand.

We know Rocky doesn't technically win that fight — but in the end, because of that set-up, we know that he really has won the battle he set out to fight. Emotionally, from a dramatic standpoint.

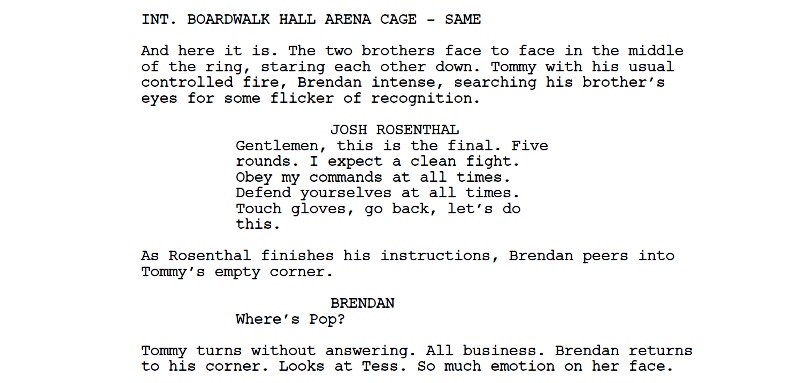

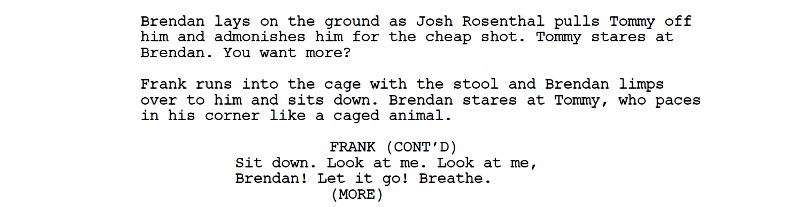

In the criminally underrated film Warrior, we have two estranged brothers facing off against each other in a final mixed martial arts tournament.

Brendan (Joel Edgerton) is a dedicated husband and father, struggling to keep his house while working a low-paying job as a high school teacher. Tommy (Tom Hardy) is a military veteran haunted by past war horrors and living a down-on-his-luck existence.

Tommy hates his brother for choosing to stay with his abusive father, leaving their now-deceased mother heartbroken. Brendan decides to stay less for his abusive father and more for his girlfriend at the time, who is now his wife and mother to his children. He has turned to the fighting tournament to win money that he needs for his family, despite his wife not wanting him to go back to that life and get hurt. Tommy wants the money for his fallen friend's widow and children.

Both are talented fighters. And both are forced to come to terms with their lives and each other in one final bout.

The drama is set up specifically in an earlier scene before the fight. Their first face-to-face moment together in years.

We know the stakes are personal. We know the dramatic and emotional subtext. All of which leads to an amazingly dramatic conclusion where Tommy's shoulder is dislocated, but he still doesn't want to quit.

But what if you're not writing a sports drama? What if your fight scene is within a conventional action thriller — how do you find the drama then?

It still falls to the buildup. Take Road House, starring the late, great Patrick Swayze. We know that Swayze's character Dalton has a zen outlook on life. He doesn't want to fight. It's always his last resort. We also learn that he has a dark past. During a fight years prior he ripped the throat out of an opponent, killing him in apparent self-defense. He's haunted by that moment, but during the climax of the film, he's forced into a similar situation again.

He fights a skilled opponent, and to survive, he must kill him. When he does, that decision fuels the fight scene with some needed drama in what could have been a routine and straightforward fight within an otherwise routine and straightforward action flick.

Do your best to inject any drama within a fight that you can — whether it's a center of the story's theme, as was the case with Rocky and Warrior, or if it's a simple nugget of dramatic backstory that elevates a fight sequence within a more conventional genre script.

Cinematic Fight Scenes Should Have Objectives, Obstacles, and Conflict

Sure, watching well-choreographed fight scenes is always pleasing to the eye, but without that drama mentioned above, they're not going to pack the punch (pun intended) that they need.

It goes beyond drama though. Each fight scene you conjure should have objectives, obstacles, and conflict within that drama.

One of the greatest fight sequences stands the test of time because the brawl centers on one single objective — one opponent getting the other opponent to do something. In this case, putting on a pair of glasses that would unveil the real world that surrounded them.

John Carpenter's They Live tells the story of a drifter (referred to as "John Nada" in the film's credits and played by Roddy Piper) who discovers that the ruling class are aliens concealing their appearance and manipulating people to spend money, breed, and accept the status quo with subliminal messages in mass media.

Nada discovers an underground resistance and is shocked when he tries on a pair of sunglasses that they've produced which reveals the true alien world around them.

He's desperate to get his new friend Frank (Keith David) to see the true world that he now knows about. But Frank wants no part of it — refusing to even humor him by trying on the glasses. Nada won't take no for an answer, leading to one of the greatest fight scenes ever filmed.

The objective that Nada has — getting Frank to wear those glasses and see the truth — drives that whole fight sequence with each and every punch, kick, and body slam.

Without that objective, it's just two guys in fisticuffs. Who cares? But because we know the truth, because we know that Nada knows the truth, and because we know that Nada wants his friend Frank to know the truth, we're invested in this fight. We know why Nada can't just give up or walk away. We're invested.

When you are writing your script and know that you want or need to have a fight scene, do your best to drive the action within that fight sequence by giving added objectives, obstacles, and conflict to enhance the drama.

Cinematic Fight Scenes Are Written Using Broad Strokes

Anyone can write a blow-by-blow breakdown with every punch, kick, and block. It's boring. It's boring to write, and it's boring to read. You’ll lose a script reader quickly with a detailed list of those elements.

The secret to writing engaging fight scenes centers on displaying the broad strokes for the reader. The essential elements that shift the fight into the next gear. You want to focus on that major punch, major kick, and major block to move the sequence forward.

If you watch a fight sequence like the iconic Bruce Lee versus Chuck Norris battle in Way of the Dragon, you’ll notice the major shifts in the fight.

Within the script, those opening blows wouldn’t be listed one-by-one. The script would simply read:

Violent and skilled kicks are exchanged until COLT (CHUCK NORRIS) CONNECTS HARD WITH A KICK TO TANG LUNG’S FACE, sending him flying to the ground.

That’s the crucial first moment. The hero is taken down, surprised. This is a major shift in the fight. Thus it is the broad stroke that needs to be featured. Then he takes more of a beating and goes down. Colt shakes his finger, which is another key moment because this instigates the coolest shift of the fight as Tang Lung now changes his fighting style.

Broad strokes feature the key moments in the fight — the dramatic shifts, the added conflicts, the failing, the prevailing, the objectives attained, the objectives denied, the obstacles cast against those fighting, and how they overcome those obstacles.

So What Do Great Cinematic Fights Look Like on the Page?

First and foremost, you want to avoid technical terms. The average reader likely doesn't know what an ax kick, side-piercing kick, or tornado back fist looks like. Stick to general terms and basic explanations.

Secondly, you want to keep fight scenes short, sweet, and to the point within the context of your script pages. Remember that epic fight sequences shouldn't be written epically as far as using prime screenplay real estate of pages that you'll need throughout your script. Leave it to the eventual fight coordinator to handle the specifics. Focus on those broad strokes.

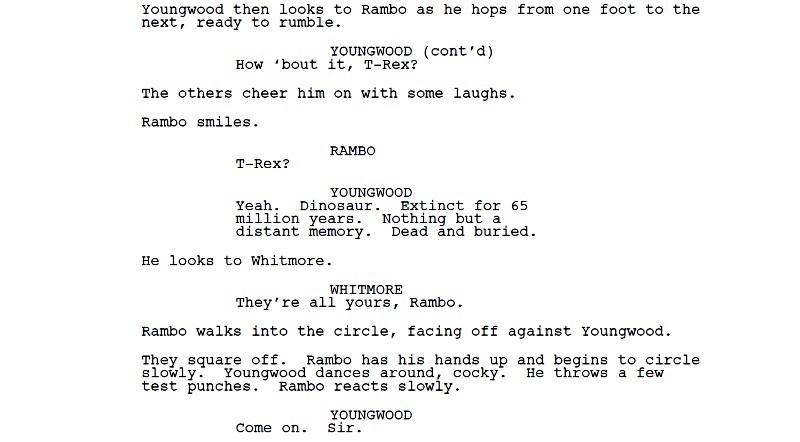

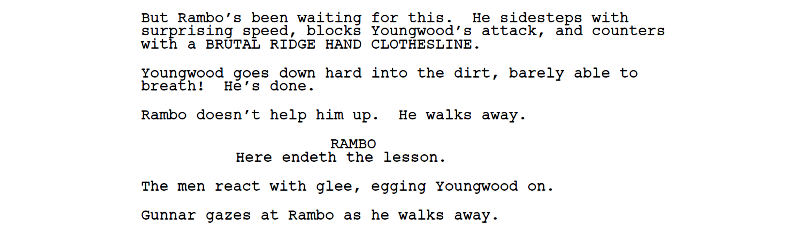

Below is an excerpt of Rambo: Last Blood, a fifth installment of the Rambo franchise I pitched to the rights owners and later had the opportunity to script.

Note: Sadly, Stallone was busy making Expendables movies and has thus far moved on from the franchise, so the project was declared dead.

In this section of the story, Rambo is recruited to train an elite group of soldiers for a secret mission. The young warriors are reluctant to welcome the aging "dinosaur" during one of their CQC (Close Quarters Combat) sessions.

The scene is short, sweet, and to the point. The blow-by-blow description is avoided, focusing only on the broad strokes. While "ridge hand" may not be a universally known fighting technique reference, it is paired with the simple term "clothesline" that most can visualize. The objective and drama of the scene are the aging Rambo proving his worth and skill to a pack of young warriors. It's subtle drama, but it serves a purpose.

And finally, here's the full climactic fight in Warrior as presented within the script, displaying the technical aspects of writing a cinematic fight scene, as well as the necessary dramatic subtext that makes it all the more memorable.

That's roughly seven to eight pages of a dramatic fight scene.

Not every blow was listed. The description of the action within the fight was kept to a minimum, allowing for the drama and the broad strokes to dictate the emotional impact beyond the dialogue within the scene.

Brendan had the objective of supporting his family and keeping their house, but he was conflicted by the notion of having to beat his brother to do so.

Tommy had the objective of winning for his Marine Corps family and for himself, unleashing some buried anger onto his brother who deserted him and his mother years ago.

And the real hidden objective within those dramatic elements was about two brothers righting their wrongs and forgiving each other.

Cinematic fight scenes are memorable when they have the elements of drama, conflict, objectives, and obstacles — all displayed within the script using broad strokes that give the reader what they need the most without slowing the read down to a halt.

Some fights are big. Some fights are small. And within each and every one of them, these elements can be utilized to varying degrees. Whatever the script or moment calls for.

Some movies have amazingly choreographed fight sequences, but the true cinematic greats are those that offer more than that.

Find the Rest of ScreenCraft's Screenwriting Basics Series Here!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!