How to Write Memorable and Compelling Monologues

How can screenwriters craft cinematic monologues that leave script readers and audiences in tears, horror, or awe?

In screenwriting, the monologue has a bad reputation. Since the screenwriting boom of the nineties, gurus and pundits have advised novice screenwriters to trim everything they possibly can within their screenplay — forcing the monologue to be taboo in the company of fast-paced and concept-driven spec scripts. Because of this, script readers almost immediately shut down when they see long blocks of dialogue from a single character at one single moment within a script.

But cinematic history tells us a rather different story. Some of the greatest movie moments have come in the form of monologues...proving that it's less about whether or not they are in your script and more about how well you write them — and why you're writing them in the first place.

The great monologues in film and television offer engaging, compelling, and thought-provoking moments that define the characters and the themes of the story.

Read More: America Ferrera's Glorious 'Barbie' Monologue Explained

Do you want to have multiple monologues in each act of your script? No. You want to choose a single one and find the perfect place within your story to present it. They can open or close a story. They can be the midpoint moment that catapults the protagonist in a different direction — teaching them what they need to know to overcome the conflict at hand.

Here we will look at monologues from different angles, using some of the best examples from film and television — breaking down why and how they work.

Before we examine those examples, let's talk a little bit about the different types of monologues and what they can accomplish within a screenplay.

Active Monologues vs. Narrative Monologues

There are generally two kinds of monologues that writers can utilize.

An active monologue is one that has the character using it as a way to take action or achieve a goal — whether it's to change someone's mind, convince them of something, or to communicate a specific point of view that the character has.

A narrative monologue usually entails a character telling a story, often in past tense. These monologues often use such a story as an analogy to the actual conflict and situation within the script's events, or as a way to explain how a character came to be the way they are or will be.

The Structure of Monologues

Monologues are like stories within the story you're trying to tell. They should have a general beginning, middle, and end — with all of the flare and compelling concepts that any whole screenplay should have.

You need to build the story they are trying to tell or set up the action or goal that the characters are trying to accomplish. You need to pepper the monologue with small twists, turns, and revelations or have each and every line portray the ultimate impact of what the character is trying to accomplish.

Each and every line in a monologue must be there for a reason. If the character is stammering, they have to be stammering for a reason. If a character is yelling, they have to be yelling for a reason. If a character is crying, they have to be crying for a reason.

Read ScreenCraft's The Single Secret of Writing Great Dialogue!

Monologues Aren't a Luxury

Writing a monologue shouldn't be looked upon as a luxury that allows screenwriters to overwrite. In fact, a screenwriter should edit their monologues more than any other element within their script that they edit.

If you're going to include a monologue within your script, there has to be a surefire reason to include it and you must sell that moment in near perfect fashion. Thus, you have to work extra hard to whittle it down to the core and cut away all of the fat in order for each and every line of dialogue within that monologue to sell that moment.

So no, they aren't a luxury. It's not your excuse to write endless dialogue with reckless abandon.

Monologues Are Singular to One Character

There's a difference between a conversation and a monologue. Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise is not comprised of a collection of monologues — it's long discussions between two characters. It's the back and forth. Those aren't monologues. The bar scene in Good Will Hunting isn't a monologue either because it involves the back and forth between two characters playing academic and intellectual chess against one another.

Monologues represent a single, nearly unbroken, moment that one single character has.

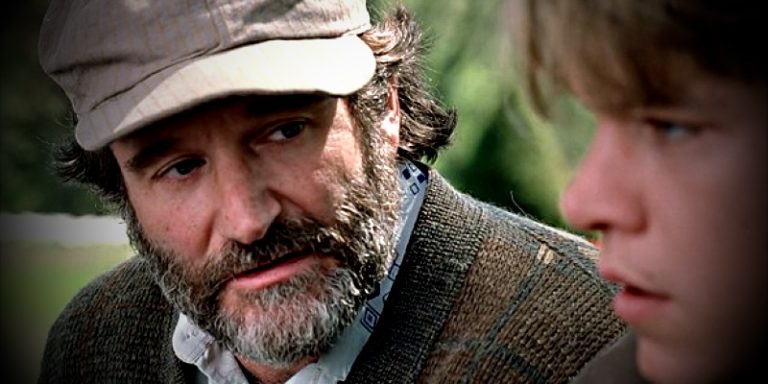

Good Will Hunting - Park Scene

This is a perfect example of an active monologue that actually takes on some of the structural characteristics of a narrative monologue as well. There are twists, turns, and reveals, like we'd often find in a narrative. But Sean is using these words to accomplish a goal — to get through to Will and challenge his confidence.

When these two first meet in Sean's office, Will examines Sean's various belongings and decorations. We see a picture of a younger Sean in Vietnam, posing with some buddies.

Within the monologue, Sean reveals that while Will may know what war is like through an academic or literary perspective, he's never been in one. He's never held his best friend's hand as he took his last breath, looking for him to help. That's a reveal.

In Sean's office, Will discovered an important detail about Sean after he mentioned his wife during his interpretation of Sean's painting. He thought he found Sean's weakness to exploit. When he pushed Sean's button in that respect, Sean reacted with extreme rage and anger — emotions we couldn't imagine attributing to this character that had an otherwise controlled and calm demeanor.

Within the monologue, we're offered the twist that Sean didn't marry the wrong woman. His wife didn't leave him. She died. And Sean was there for every minute of her suffering through cancer without a damn thing he could do about it.

He has clearly proven that Will can't possibly know who Sean is by looking at a painting. He can't possibly portray himself as a superior because he hasn't truly lived or loved. Sean then masterfully flips Will's assertions by saying that just because Will is an orphan, he can't possibly know how difficult his struggles have been because he read Oliver Twist.

This monologue had purpose. Sean's goal was to take action and push against Will's mind games in order to help Will reach out to him.

And here's the most important factor of this — or any — great monologue. If you take it out of the script or movie, nothing else beyond it works. If this monologue isn't in the story, Will doesn't open up to Sean. Because he doesn't open up to Sean, he never confronts his inner demons and he never experiences the love of a girl he just met. He likely goes back to his old ways and ends up in jail.

Jaws - The Indianapolis Speech

This is the ultimate narrative monologue, as Quint tells the story of his experience during the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis and resulting shark attacks as the remaining crew were left in the ocean waters, waiting for rescue that wouldn't come until a majority of the men were eaten alive.

There is no goal for Quint to tell this story. After the three characters drunkenly compared their various scars, the Chief asks about a certain one. Quint's eyes narrow as he reveals it was from the Indianapolis, a story that shark specialist Hooper is familiar with. Quint goes on to tell the harrowing and horrific story.

This monologue is placed in between the action of them hunting a deadly shark. By this point, Quint was seen as nothing more than an obsessed and cranky captain — almost like an obsessed Captain Ahab. But when we hear him narrate this story, we learn why he is obsessed with finding and killing the shark. And we learn that he's not as invulnerable as we thought. It is also a foreboding moment of foreshadowing as his fate is about to be decided in the coming hours — a fate that will force his history to come around full circle as he dies violently at the jaws of a shark.

The way he tells the story — as if they're around a campfire — gives the audience an equally foreboding feeling leading into the third act of the film. We learn how dangerous sharks truly are, beyond what we've seen with a few deaths on and off-screen. And we know that if Quint is as scared and haunted as he was to this day telling that story, then we should be as equally scared for those characters going into the climax of the film.

It masterfully sets the tone that drives us further into this insane quest to kill a seemingly unkillable monster of the deep ocean blue.

A Few Good Men — "You Can't Handle the Truth" Scene

This scene starts with back and forth between two characters and ends with back and forth that leads up to a major moment where Jessep admits that he ordered the Code Red. But it's the middle monologue that is singular to the character of Jessep alone — void of interruption — that shines and is an impacting and engaging moment of this active monologue.

The purpose Jessep has is to communicate his frustrations with this questioning of his honor, code, and duty. Each word is delivered with a punch as we learn the true nature of this complicated character that we are supposed to hate. When he delivers this monologue, we understand why he thinks he's right in what he does and how he does it. Part of us may even agree with him. And that is the purpose of this dialogue. The writer is offering the character a way to justify his actions.

It's one thing to just declare that a character is evil by eliminating a no-good soldier. When an active monologue like this is utilized, we're offered a more complex antagonist.

It forces us to confront our own beliefs as we walk away from the movie.

"Was Jessep justified?"

"He didn't really kill Santiago. He was disciplining a soldier that went outside of the ranks."

"Don't we want people like Jessep in charge of our freedom and protection?"

"If we don't have people like Jessep on that wall, who would be able to do it?"

While our ethics and morals may answer those questions, the point from a screenwriter's perspective is to get audiences to think.

When you write active monologues, there has to be a purpose for them. They can't be used as a mere cheat or luxury to write the inner feelings of your characters because you can't figure out how to show rather than tell. Any and all monologues must be a call to action or put the story's events into context to offer added depth.

Inglourious Basterds - The Farmhouse Scene

Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds offers a masterful scene that by our own definitions within this article may not qualify as a monologue at first glance. There is some back and forth as Landa poses some questions to the farmer. However, if you pay close attention, every question Landa asks the farmer is rhetorical. The Farmer doesn't even answer all of them — and the answers he does offer are insignificant because Landa has a predetermined agenda. Each question he asks during his monologue isn't just rhetorical — he's using them to inject more and more fear into the farmer and those hidden below them.

Yes, the Jewish people hiding underneath the floorboards are established during Landa's monologue. He knows that they are there. And that is what makes this monologue great.

Tarantino could have placed Landa's monologue in almost any scene throughout the script. However, his decision to place it in this particular scene is masterful because it creates ultimate tension as we know that there are people hiding underneath this conversation — both figuratively and literally.

At first, we don't know. But there are clear fears and suspicions that this Nazi "Jew Hunter" is looking for someone, and that someone may be in this farmhouse. Then, during the middle of the monologue, we are offered a glimpse of them — confirming those fears and suspicions, thus enhancing the tension and suspense as Landa continues to speak.

The actual words within the monologue then showcase that this character is truly evil. The dialogue manages to give us an explanation for how a Nazi soldier like Landa feels about the people he is hunting — comparing a Nazi soldier to a hawk and a Jewish person to a rat. His comparison builds and builds as we wonder how all of this applies to the situation at hand.

When he explains that a Nazi soldier — a hawk — knows where to look for hiding Jews, he stands out because he also knows where a "rat" would hide as well. When this reveal is given within the monologue, our hearts sink deep because we know that he knows about those hidden underneath him.

Placement of your monologue is key. Had Tarantino situated this within any other scene in the script, it would surely have still offered a certain amount of impact and information about this truly evil character — but it would have been void of the tension and suspense of that farmhouse and the people that were hiding from the Nazis.

The Newsroom - "It's Not, It Can Be" Scene

We're going to shift to television, primarily because within the last decade, television has become cinematic in scope and content. And also because it was the only way we could celebrate one of the greatest monologues we've seen in both movies and television.

This scene from The Newsroom is pure Aaron Sorkin, matched with the brilliant delivery of Jeff Daniels.

The scene itself is six minutes long and begins with back and forth between multiple characters. It isn't until almost three minutes into the scene where Jeff Daniels's McAvoy delivers a powerful rant about politics and how America isn't the greatest country in the world.

The key to this monologue is one that all writers need to consider utilizing — the build-up.

Most of the greatest monologues are a result of an emotional build-up where the character almost has no choice but to finally speak up.

Jessep in A Few Good Men (also written by Sorkin) unleashed those words above after the build-up of Kaffee verbally attacking him on the stand.

Sean in Good Will Hunting delivered the heartfelt speech after the build-up of Will trying to push his buttons, resulting in a physical confrontation.

Quint in Jaws told the haunting story after the build-up of the shark hunt earlier in the day, followed by the scar comparison game leading to the reveal of Quint's scar left over as a result of his experience during WWII.

In this The Newsroom scene, McAvoy is part of a political panel. It's clear that he doesn't want to share how he really feels about politics in this day and age. But he's constantly being pushed to that final outburst because of the politically correct rhetoric that he's listening to from the left and right. Even when the young student asks the panelists to explain why American is the greatest country in the world, McAvoy is hesitant to speak the truth. But they keep pushing him to give an honest response.

He finally does.

And the content of that response is so powerful, bipartisan, and full of truth, it resonates with the audience. It's eye-opening to many. It is the type of dialogue that gets you thinking and questioning your own presumptions. In short, it's thought-provoking.

So this monologue manages to master the build-up aspect of writing great monologues, while at the same time offering dialogue that impacts the audience and forces them to give it even more thought.

Maybe it changes minds? Maybe it gives people another perspective to consider? Maybe it identifies with people or people identify with it? Maybe people object to it?

Whatever the case may be and whatever response it invokes, it's thought-provoking. And that is what most great monologues need to do — they need to stick with the audience for whatever reason. Whether it's offering a thought-provoking dialogue within the script's story or whether it's reaching outside of the story and creating a response from the audience.

As you are determining if a monologue is needed within your story, you must first decide between writing it in active or narrative form. Then you must create a structure that is a story in and of itself — complete with a beginning, middle, and end. But before you commit to writing a monologue, make sure that it's not an excuse to avoid editing your dialogue and always ensure that you're not using it as a way to tell rather than show within your story. And then remember that a monologue is not a monologue when it consists of back and forth between two or more characters. It is always a singular moment of a singular character.

You can use other characters to create an amazing build-up — or you can use the tension and suspense of another layer of a scene to have the monologue be a build-up of its own (Inglourious Basterds) — but always remember that whatever it is that you write within that monologue must be pared down to its core and must always be written in a way that leaves a lasting impressions with the audience.

Easier said than done, but doing so makes it easier to write.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook!

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!