How Rocky Debunks the Screenwriting Guru Book Save the Cat

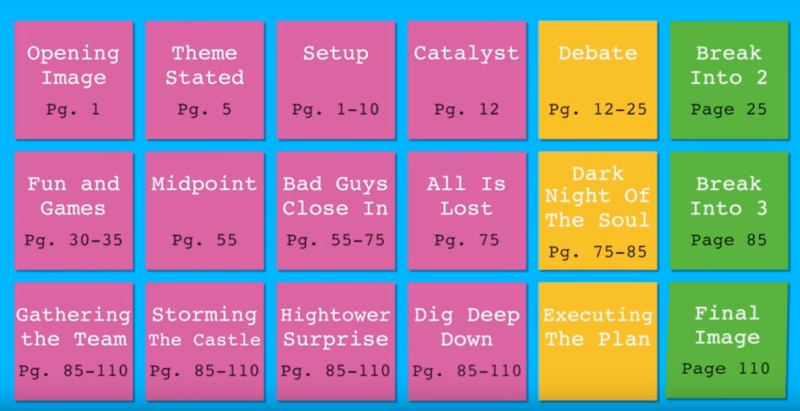

On page 5 your theme has to be stated. On page 12 you need to have your catalyst moment presented. Your break into Act II is required to be on page 25. Your midpoint has to be on page 55. Your all is lost moment must always be on page 75. And then your final "image" has to be on page 110. Right? Not according to Rocky, and most other successful screenplays.

In a world and industry always in search of quick solutions and easy formulas to follow for success, we often forget what really drives us to greatness — truth, heart, and instinct — three elements that can be found throughout the Rocky screenplay.

In the context of screenwriting, those elements have been seemingly replaced by the notion that secret formulas can make up for that.

Saving the Cat

The late Blake Snyder wrote what became a pinnacle screenwriting book for any new screenwriter coming onto the scene — Save the Cat. Originally published in 2005, Snyder wrote the book in an attempt to explain and break down the various beats that he felt most successful screenplays should have.

His first spec screenplay sale was in 1989 for the script Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot — which ironically would later star Rocky actor and writer Stallone. Snyder's script sold for $500,000 after a major studio bidding war. He went on to sell 12 more original screenplays during the screenwriting boom of the 1990s, and was named "one of Hollywood's most successful spec screenwriters."

In his book, Snyder put major emphasis on the importance of structure with what would become celebrated as the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet, which includes the 15 essential "beats" or plot points that all stories should follow.

The book takes that specific beat declaration to the next level by showcasing what script page numbers such beats should occur on.

So that means that every successful screenplay in Hollywood is 110 pages long and adheres to these directives, right? No. Far from it.

Rocky vs. Save the Cat

The Just Write Youtube Channel recently posted an excellent video entitled Rocky: Why You Don't Need Writing Formulas. Within minutes, like most can do with other successful movies and their scripts, Rocky proved that the declarations behind Save the Cat are false. And furthermore, the Rocky screenplay teaches screenwriters a true key factor of its success — empathy, and the time it takes to create such an emotion in the audience for a character like that.

Here we delve into the video and share the blow to blow account of how this underdog of a script — which later was nominated for an Academy Award — goes on to debunk much of what Save the Cat's beats and page breakdowns stand for. Save the Cat certainly has its worth as a learning tool, but thanks to Rocky and many other successful screenplays, we know that there is no one single answer for every screenplay.

When Should the Story Start?

This isn't about what scene should come first. Instead, we're discussing when the actual core of the concept takes hold and catapults its character(s) into the story.

According to Save the Cat, this moment has to happen on Page 12, in what the book refers to as The Catalyst — similar to what Syd Field years before referred to as The Inciting Incident.

“Telegrams, getting fired, catching the wife in bed with another man, news that you have three days to live, the knock at the door, the messenger. In the set-up you, the screenwriter, have told us what the world is like and now in the catalyst moment you knock it all down. Boom!”

This is when something happens that launches the character into action.

Snyder wrote, "When I'm writing a screenplay, my catalyst moment will float around for the first couple of drafts. the set-up will be too long, the story is clogged with details, and that page 12 catalyst beat is somehow, mysteriously, on page 20. Well, cut it down and put it where it belongs: page 12. And when you start trimming all your darlings away, you'll suddenly realize that's why we have all these little structure maps — all that boring detail was redundant or you weren't very good about showing it economically."

The problem with this simplification in comparison with one of the best screenplays ever written — Rocky — is that some of the best character moments are comprised of that "boring and redundant" detail.

The catalyst moment for Rocky happens on — wait for it — Page 55.

This is the scene where Rocky is given the opportunity to take on the fight of a lifetime — the big chance he's been waiting for.

For nearly 54 pages before that, the screenplay is dedicated to one single thing — making you care about the characters. Creating empathy for your characters isn't about checking a beat sheet box and moving onto the next. It's a continual process.

In the first hour of the film, we are repeatedly shown how life is pushing up against Rocky and telling him that he's no good.

- He lives in a run down apartment

- He works a thankless job as an enforcer for a loan shark

- He gets stiffed for fight earnings

- He is insulted over and over by different characters

- He walks down cold and empty streets, all alone

- He talks to pet turtles and pictures of his family — showcasing how lonely he is

According to Save the Cat, this is all redundant. Most agree — as does history — that such moments are drastically effective and essential for the success of the screenplay. Yes, bad screenplays do this poorly with overly long and drawn out moments that take up a majority of the first act. But in the case of Rocky, these moments are often quick, precise, and there for a reason.

The video goes on to point out that most trying to apply Save the Cat's catalyst moment to Rocky would point to earlier scenes like Rocky getting his locker taken away from him or him talking to Adrian in the pet shop.

This points to the true problem behind Save the Cat and its undying following — the beat sheets are applied retroactively when trying to use popular screenplays as proof that Save the Cat works. It's a matter of interpretation. While some may believe that this solidifies Save the Cat's directives, it actually hinders the validity of them at the same time. Hindsight is always 20/20.

You wouldn't read that book and write a screenplay like Rocky. Instead, like the video observes, you'd be forced to drop those early scenes of character development. That scene where he walks the disgruntled and disrespectful girl home? Gone. You'd cut the scenes of him walking alone, as well as many others. This would leave you with maybe three scenes before that catalyst moment — a scene at the gym, a scene at home, and a scene at the docks where Rocky is collecting. Sure, that may result in following the formula presented by Save the Cat, but in exchange you've butchered one of the greatest cinematic characters and stories ever written.

Rules vs. Guidelines

The core of Save the Cat and its beat sheets should be better interpreted as some noteworthy guidelines — not rules — to follow. Snyder's career was bred during a time when studios were buying spec scripts left and right. The pressure to write such high concept scripts as quickly as possible was evident. The need to have scripts get into the meat of the story and concept as quickly as possible was crucial.

While it is true that today's industry has a similar demand, those within the industry will also tell you that scripts that follow the page-by-page formula of Save the Cat are often those that are the most transparent and thus, the most easily dismissed. While it may read as a Catch 22 to most, the key take away is that screenwriters should avoid subscribing to the notion that scripts need to hit certain beats on certain pages in order to be successful. Such a concept is utterly ridiculous and misleading.

Some excellent guidelines can be learned from the book, but they should be nothing more than additions to your storytelling toolbox that offer options to help tell your story if things aren't progressing as you would have hoped. The same can be said for all screenwriting guru books.

Why Those Rocky Scenes Matter

The scenes where he's an enforcer? He still showcases a heart while enforcing, which adds to the empathy of the character beyond a simple "save the cat" box that is checked.

When he sees the drunk passed out outside of the bar? He showcases continual heart when he picks him up and brings him in.

When he walks the rude girl home and lectures her? We see that even amidst the ridicule from the person he's trying to help — he cares.

When he can't get a trainer, loses the locker, and is insulted over and over and over? We learn how much of a fighter he truly is because he continues on and on through all of that — while never losing his heart.

All of these scenes would have likely been cut under the guidelines of Save the Cat.

Writing Is Less About Chasing Trends and Formulas — and More About Finding Emotional Truth

Chasing trends, inserting scenes within predetermined slots, and hitting specific beats at specific pages in your script won't give you anything beyond average results at best — especially considering the masses that attempt to follow the same paradigm designated by a guru book that so many people read. A paradigm that industry insiders quickly see right through.

Instead, look to screenplays like Rocky for what to really seek out as you are developing and writing your own.

Sylvester Stallone was feeling everything Rocky felt in his own life. He was broke. He had to sell his dog for $50 to make ends meet. He was told that he was washed up. He couldn't get hired for jobs. His struggle for success after years of rejection after rejection became Rocky's story — emotional truth.

Screenwriters should focus less on gimmicks and secret formulas that don't exist — and more on telling stories as they individually need to be told. When there is emotional truth to the characters — whether conjured from your life or that of others — and it is injected into whatever genre and character type, audiences will respond. The industry will take notice. Compare and contrast the strengths of that with empty paint-by-the-numbers character and story arcs and you'll hopefully see that emotional truth matched with whatever story you're trying to tell is more dependable.

You'll stand out not as one of many — as would be the case with stringent Save the Cat followers — but one of the few that have told amazing, unique, and original stories.

The general guidelines and expectations of the industry are inescapable, sure. You do need to engage the reader early. You do need to deliver on concepts early. You do need to launch characters into the story as soon and possible. Save the Cat does offer guidelines to utilize in that respect.

But while some stories can easily adhere to the Save the Cat page beats, most would suffer from doing so.

The lesson learned here should be to never subscribe to the idea that there is only one way to tell a story.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter and Facebook!

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!