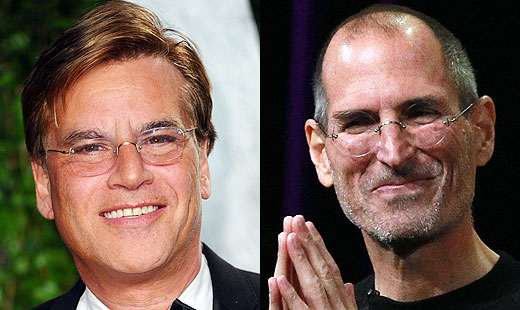

Inside Telluride: Aaron Sorkin On Writing Steve Jobs

Though Room has received the most rapturous response of any narrative film at the 42nd Telluride Film Festival, Black Mass and Steve Jobs are certainly the most high-profile and hyped titles in the lineup. The latter, of course, is written by Aaron Sorkin, one of the most celebrated and iconic film and television writers of the last thirty years. He’s one of the few screenwriters to have achieved wide, mainstream fame and to have become a brand. And like most figures who reach his level of success and exposure, he has even been lovingly parodied.

His projects include A Few Good Men, The American President, Sports Night, The West Wing, Studio 60 On The Sunset Strip, The Newsroom, The Social Network, Charlie Wilson’s War, and Moneyball, and that of course doesn’t take into account the myriad dialogue polishes on big studio movies he’s been hired to do.

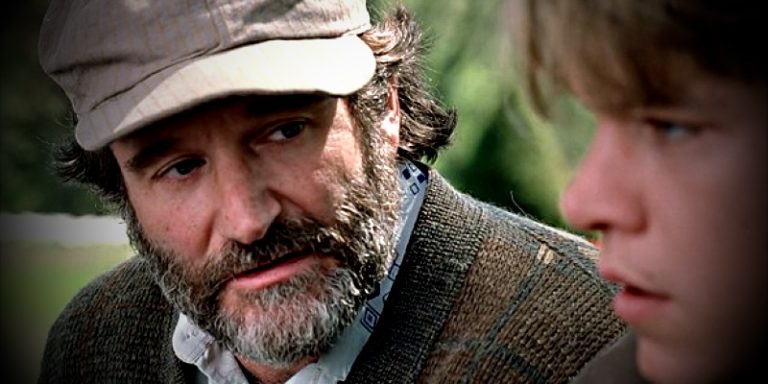

During an open discussion at Telluride with his fellow collaborators Danny Boyle, Kate Winslet and Seth Rogen, Sorkin talked about how he got involved with Steve Jobs and even offered some insights into his writing process. Here are the highlights:

- Sorkin was inspired by the Walter Isaacson biography on Jobs, but actively sought to avoid doing a straight-up, “greatest hits, cradle-to-the-grave” biopic because he felt audiences have become inured to that structure. He wanted to emphasize depth over breadth, to offer a “painting” of Jobs rather than a “photograph.”

- Sorkin described himself as “really a playwright who pretends to write movies” and remarked that in trying to crack the script, he began as he always does: knowing nothing. “You always start out by banging your head against the wall, and you have no ideas.”

- Eventually, he seized upon the notion of structuring the movie as “three [one-act] scenes that took place in real time in a very claustrophobic space” because it suited his playwright tendency.

- He approached Sony and producer Scott Rudin with this structurally radical, even experimental idea and asked them how far they would let him go in that direction before stopping him and pushing him back into a more conventional place. He was surprised when they wholeheartedly endorsed his approach and told him to go for it.

- Sorkin spent approximately one year researching and one year writing the project. He ended up with a 200-page, dialogue-driven screenplay that centered on three Apple product launches. Sorkin cautioned, however, that the story isn’t concerned with how the three iconic Apple products were invented; rather, it uses those product launches as natural, conflict-riddled backdrops to provide three telling windows into who Steve Jobs was as a person.

- Danny Boyle came onboard and viewed the project as a natural companion piece to Sorkin’s seminal The Social Network. He noted that in that film, the characters remained seated for most of the film and only stood up for critical moments in the narrative. For Steve Jobs, that construction was inverted, with the principals almost always being on their feet and moving around.

- Boyle elaborated that the camerawork of the film—particularly the Steadicam sequences—were used not only to capture but also to dramatize the film’s events in a very specific way. He noted that, given that Sorkin’s script was intentionally repetitive in terms of venues and visuals (all centering on interiors and Apple product launches), he strove to customize the camerawork to reflect the different emotional energies of the three (one-act) scenes. The first act was filmed so as to emphasize “young energy” and the telling of a “creationist myth.” The second act was staged much more elegant and deliberately, an example of “arch storytelling” to reflect how Jobs and Apple had evolved as a person and company, respectively. And the third act was filmed so as to emphasize the Apple mandate of “simplicity as [the] ultimate sophistication.”

- When asked about the dramatic liberties that Steve Jobs—and any biopic, for that matter—takes, Sorkin noted that “there’s a difference between journalism and art.” He shared the story that, in working with the late Mike Nichols on Charlie Wilson’s War, Nichols told him that “art isn’t about what happened.”

- Sorkin reiterated that the intention with the screenplay was to emphasize “five points of friction in Steve’s life…[and to] dramatize them in this place in this compressed period of time…it’s not a photograph, it’s a painting. The fact that a particular conversation never happened…wasn’t important to me. There was a more important truth that I didn’t’ want to betray…I wasn’t attempting to do an impersonation.”

- When asked about his writing process, Sorkin joked that “to the casual observer, my early writing process would look a lot like lying on the couch and watching ESPN. But there’s stuff going on.”

- Sorkin elaborated: “There really is a lot of internal cooking that has to go on before you start writing. I don’t like to fingerpaint…’let’s just explore and see where this goes.’ I want to be fully loaded up. I worship at the altar of intention and obstacle. Someone wants something and something is getting in their way. That has to be present in every scene. Once you have that, you can use that as a clothesline to hang the things that the movie is really going to be about.”

- Sorkin on how he writes: “Nobody is anywhere near me [when I write]. I do act it out, I say it out loud, I’m very physical when I’m writing, and sometimes when I’m very excited, when it’s going well, I’ll forget to keep typing and I’ll end up two blocks from my office.”

Perhaps most encouraging to aspiring screenwriters everywhere, Sorkin revealed that he has “far fewer good writing days than bad writing days. Most days end with your having not done anything and not knowing what you’re going to do tomorrow. Most days you feel stuck, and you feel like not only are you not going to be able to write this, you won’t be able to write anything ever again.” Let that be a lesson: even the undisputed greats struggle with the process each and every day. They aren’t great because writing comes seamlessly to them. They’re great because not only do they have and sustain the ability to recognize their own talent and the fact that they have something to say, but they also constantly commit to honing their craft and perpetually putting in the work.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!