Screenwriting Basics: How to Write Cinematic Phone Conversations

You've got two or more characters in different locations talking through a phone, radio, or commlink — how do you cinematically format these types of scenes? We’re going to explore how to properly format cinematic phone conversations for this installment of our ongoing Screenwriting Basics series.

This is one of the most common and basic questions screenwriters struggle with. But an even more common misconception is that the answer lies just within the format. It's more than that.

The key element in the way we've written out that question is the word cinematic. We'll take a step back for a moment and cover the idea of writing cinematically before we tackle the basic formula of how you should portray such a scene within the confines of screenwriting format.

Writing Cinematically

Writing cinematically is a must for screenwriters trying to break through those Hollywood walls. There is a genuine difference between how a spec script is written — scripts written under speculation that they will be sold and produced — compared to how seasoned screenwriters write assignments or craft shooting scripts.

Spec scripts need to be written with cinematic flavor. That's one of the secret ingredients of every successful spec script — making that script reader see your film through their own mind's eye as quickly as possible.

To accomplish that, spec scripts have to be void of complicated formatting, instead offering the best possible and most easily digestible description of what the reader is supposed to be seeing. We're not talking specifics here, mind you. They don't need to know every subtle detail of the action, characters, and environment — save that for when you write your novel.

However, script readers do need the broad strokes of what they are supposed to be seeing. And any time the flow of the script is halted by a complicated or unclear format that doesn't communicate the visual as quickly as possible, you've halted any momentum of the read.

And make no mistake — when you're writing spec scripts, you're writing for the script reader.

Writing for the Script Reader

When trying to determine how to write what many screenwriters feel are challenging scenes like phone conversations, it's important to remember who you are writing for.

First and foremost, you're not writing for a director, editor, or actor, so don't worry about suggesting even the most minimal of camera placements, editing suggestions, or performance cues. You'll see what we mean as you read on below.

Spec scripts are explicitly written for script readers. Those script readers will start out as interns, assistants, or contest judges. Then if all goes well, those scripts will be read by development executives, managers, agents, and producers.

That's a lot of titles, but in the end, they are all script readers. They are there to experience a cinematic story, plain and simple. They're not breaking down the script from a director's point of view, an editor's point of view, or a lead actor's point of view. Shots are not being determined. Camera angles are not being logged. Performance notes are not being made.

All the spec script writer needs to worry about is communicating a truly cinematic experience to that script reader so they can determine if it is engaging and appealing enough to pass it up the chain of command.

How does that factor into how a phone conversation is written within a spec script? Let's touch on the role that format plays within a spec script first.

The Role of Format

Screenplay format within the confines of a spec script is there for one reason — to communicate what the script reader should be visualizing.

We start with INT or EXT to communicate the area that a character is in.

Then we offer a LOCATION to communicate what setting that character inhabits within a scene.

DAY or NIGHT is used to dictate what we should be envisioning from a time perspective, as well as the visual of daylight or darkness.

What then follows is scene description offering some more specific broad strokes.

That's it. Those are the basics, right?

Those basics are embedded into the minds of script readers, to the point where they are fast and easy cues that the reader picks up and translates within milliseconds — at least when communicated in uncomplicated and straightforward fashion.

When readers see a new LOCATION, complete with INT, EXT, DAY, or NIGHT, their brain knows to make that switch. It tells them what to visualize and what should be seen in their mind's eye — like a built-in movie theater screen within their mind.

Any time you mess with that, the pacing of the script slows down, and the script reader is forced to essentially pause that movie in their head, reread the format, and take the additional time to reinterpret it. That's not a good thing for any spec script.

The format is there for a reason and plays a pivotal role in the visualization of your script.

How to Tackle a Phone Call Cinematically

We've talked about what it means to write a cinematic script. We've talked about who you are writing that cinematic script for. And we've discussed the role that format plays in the reading experience of your script.

Now let's put everything together and figure out the best way to write a cinematic phone conversation within a spec script.

Option #1

The most common option you've likely read about is INTERCUTTING. This is where you set up both locations using location headings and establishing what characters are in those locations. You do this only once and then type INTERCUT - PHONE CONVERSATION, followed by seamless character names and dialogue with no break in the different locations and no specific description as to who we should be visualizing beyond the scene description being used, thus forcing the reader to decide what to visualize.

Option #2

This second option is slightly more cinematic, offering more specific cuts to each location each character is in and using (V.O.) to determine who is not on screen and also possibly using (into the phone) to ensure that the script reader remembers that the person on screen is talking into the phone. This helps when there may be other dialogue shared with other characters on the screen while the featured character is also on the phone.

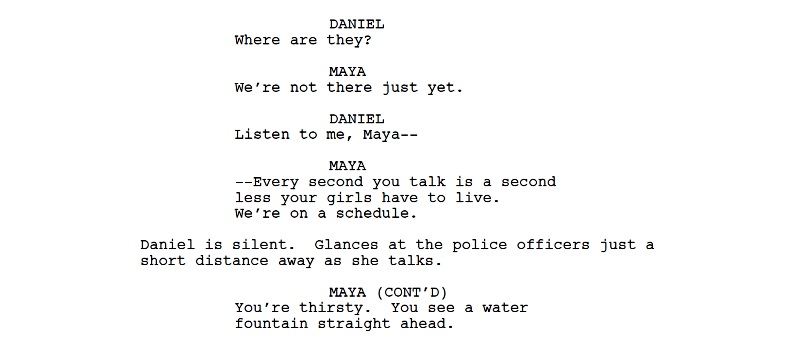

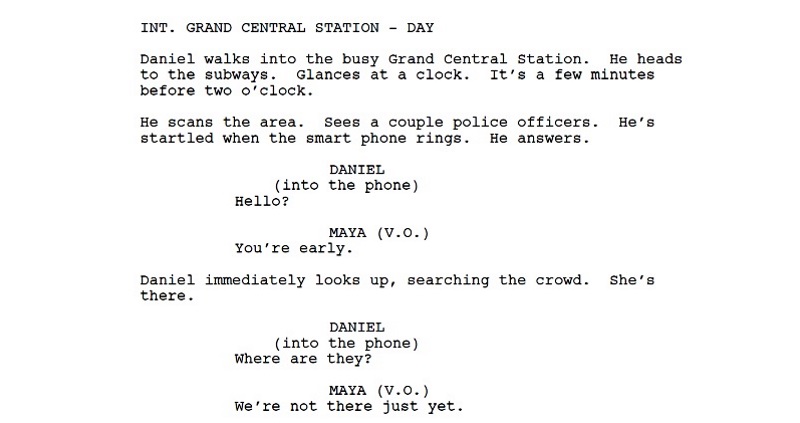

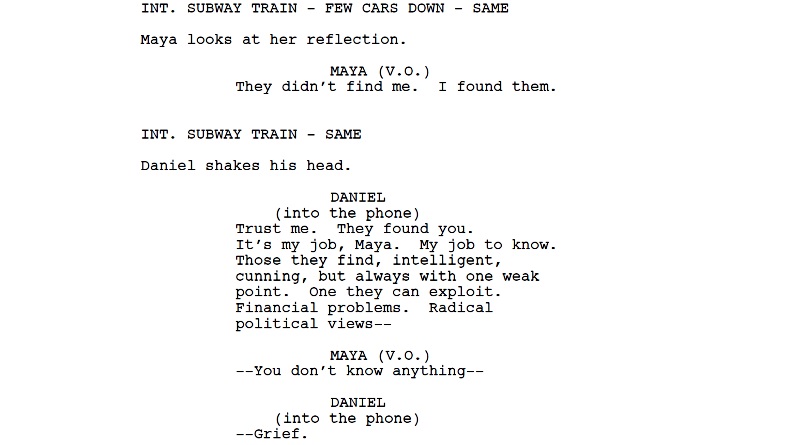

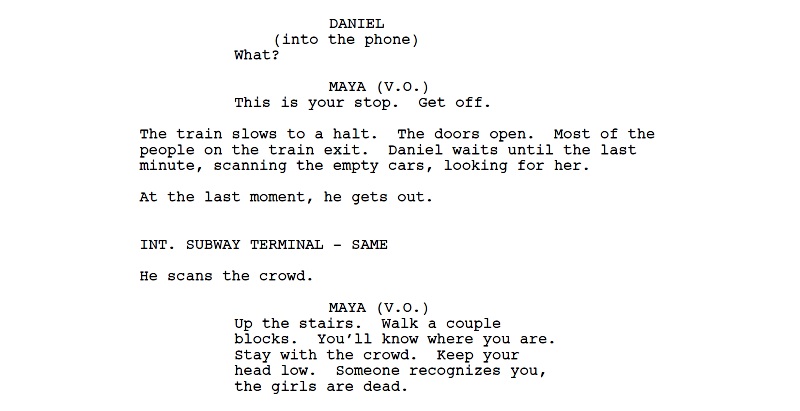

Here are two versions of the same sequence taken from the 2014 ScreenCraft Action Thriller Winner The Enemy Within, each using Option #1 (Intercutting) or Option #2 (Location Cuts). Review them, and then we can compare and contrast.

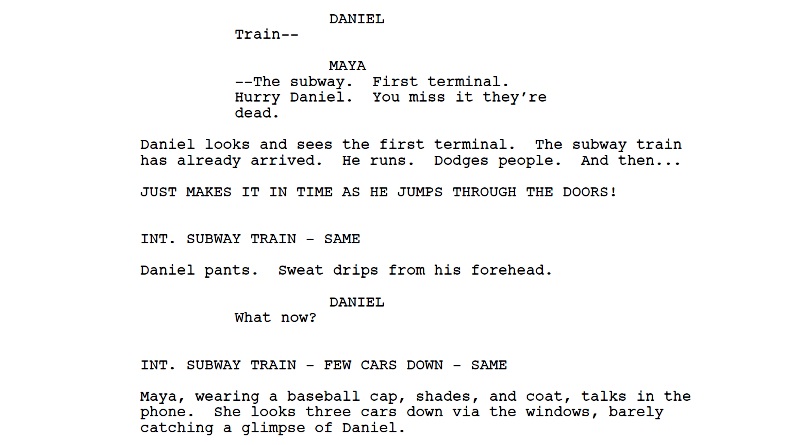

Option #1 (Intercutting) Version

The script sequence began by establishing the two locations that the two characters were in. Then INTERCUT - PHONE CONVERSATION was utilized to instruct the reader that they were in charge of envisioning who was being seen on camera at any given time.

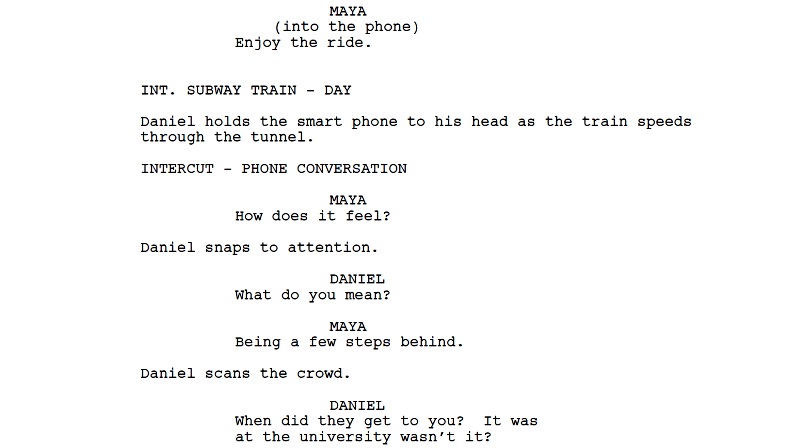

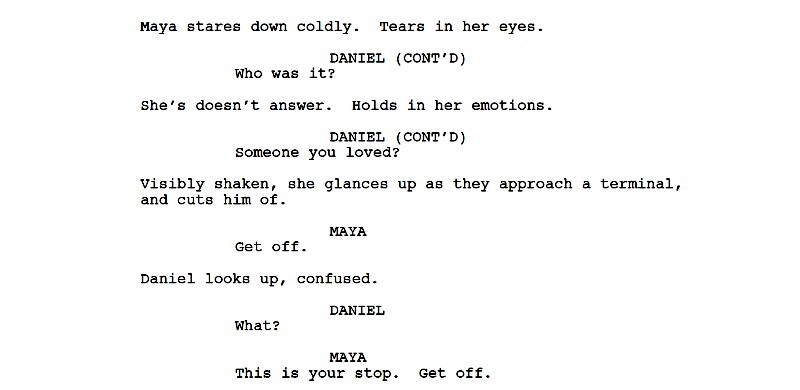

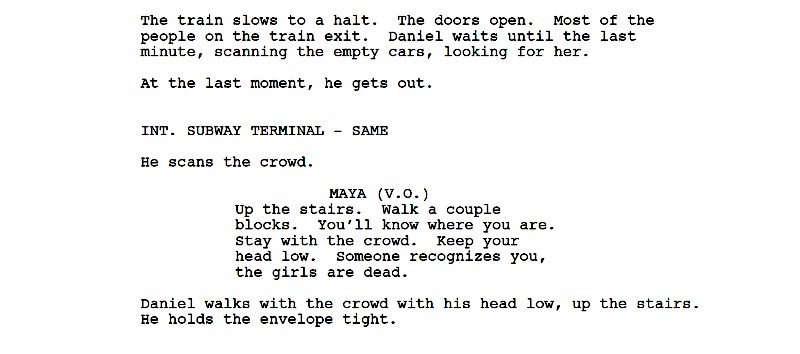

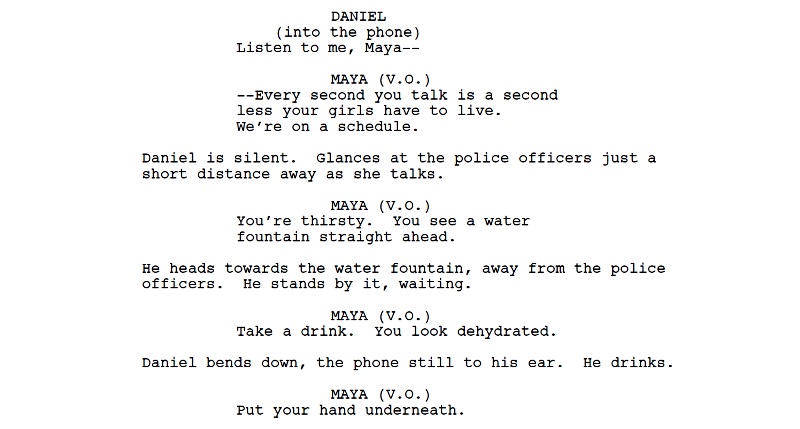

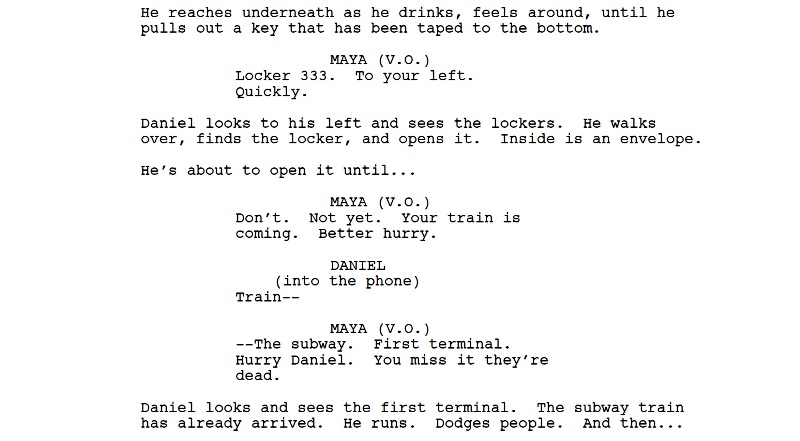

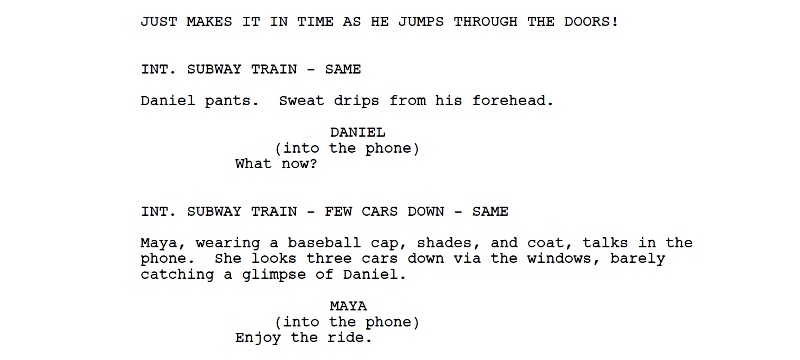

Now let's take a look at the original version of this sequence — the one that hasn't been altered and is present in the actual script.

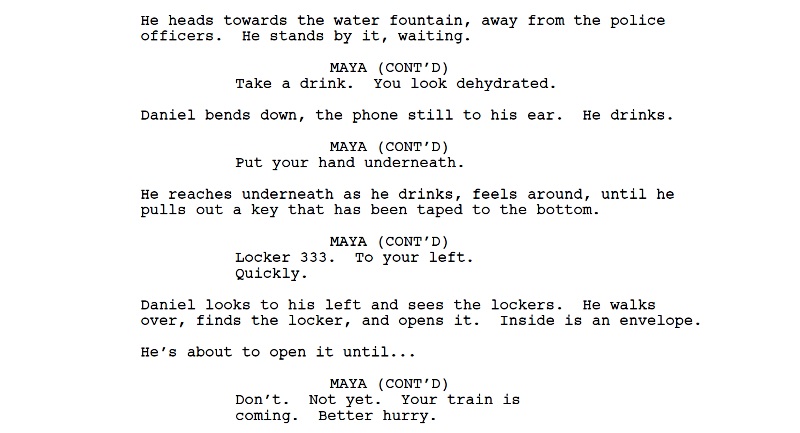

Option #2 (Location Cuts) Version

With this version, the writer dictates what character should be shown in what location. This is accomplished by using SAME where DAY or NIGHT would normally be within the location heading, in order to communicate to the reader that these different locations — and actions and dialogue within — are happening at the same time. (V.O.) is used to communicate that the character is not on screen, but heard through voiceover, while (into the phone) is showcased to ensure the reader knows that the character on screen is talking into the phone, as opposed to anyone else that may be visible near them.

Which One Is Better?

There is no specific rule that states either one of those options is right or wrong. However, one of them is arguably more cinematic — Option #2 (Location Cuts) Version, which is also the original format utilized in the actual script.

Remember, you're writing for the script reader. Not anyone else. So you have a little leeway as far as dictating how a scene should be visualized. In this case, you have to think like an editor in order to make the scene more cinematic.

Read ScreenCraft's Why Screenwriters Should Think Like Film Editors!

Tension is built through the choices of what character is or isn't being shown on screen. With Option #1 (Intercutting) the writer is asking the reader to make that decision. That forces the script reader to slightly pause that movie playing within their own mind's eye. You don't want to do that.

Don't forget that location headings are processed within their mind in milliseconds, so that's not stopping the reading experience. And the elements of SAME, (V.O.), and (into the phone) are established quickly and also become those millisecond cues that they need for visualization. One could argue that (V.O.) and (into the phone) are overused and a waste of script real estate, but the consistency of those millisecond visual cues actually can help the script reader experience a more cinematic read.

Again, there is no right or wrong answer. Some script readers may prefer one over the other. But before you make your decision on which version you choose, ask yourself, "Which one is more cinematic?"

And keep in mind that the answer may fall in the context of whatever scene you are writing. If you have a scene that has less action and movement, and entails two characters in different locations but in somewhat static positions within those locations, Option #1 (Intercutting) may be the way to go.

But if the sequence calls for a little cinematic flair, using the different actions and visuals for purposes of suspense, tension, action, and reveals, always go the more cinematic route.

And before anyone asks, do your best to avoid using the split screen. That's a choice for the filmmaker to make and it's hardly cinematic — at least within the realm of writing cinematically.

Find the Rest of ScreenCraft's Screenwriting Basics Series Here!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook!

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!