Does a studio script reader ever pass on scripts written by celebrated writers? Do they get burnt out easily after reading so many scripts? Do they receive proper training before being entrusted with writing coverage for scripts? If you’ve always craved for the truth behind these Hollywood gatekeepers, you’ve come to the right place.

My name is listed below, and yes, I’m a former studio script reader. In our inaugural post Confessions of a Studio Script Reader, I broke the fourth wall and opened up to shed a little light onto the faceless silhouette of the studio script reader — the very person that holds your destiny in their hands.

In Part II, I got a little more specific and confessed my feelings about the common question of whether or not you, the screenwriter, should develop a backstory for your villains.

With Part III, I'm getting back to those juicy behind-the-scenes details of what it's like to be a studio script reader.

You’ve likely watched interviews, been in the audiences of screenwriting conference panels, or read blogs written by dozens of different — and better — versions of me.

The story of how I got into this celebrated and often bemoaned position is no different than most, so we won’t get into that. I was either an intern that became an assistant, a struggling screenwriter that had a knack for story analysis which found himself at the right place at the right time, or a writer that talked a studio development executive into giving him a shot — maybe a little of all three.

The origin story of a studio script reader isn’t often that exciting. And the job itself is far from glamorous.

The reason I’m here is to confess, explain, and try to shed a little light onto the faceless silhouette of the studio script reader — the very person that holds your destiny in their hands.

Note: Since I’m a former studio script reader, I’ll be confessing from the perspective of my past self in the present tense.

Confession #1 — "Yes, I have passed on scripts written by acclaimed writers. Why? Because they weren't that great."

Here's one of the most interesting truths about the industry — just because you've seen some success as a screenwriter, filmmaker, or actor doesn't mean that everything you do from that point on is brilliant.

While I can't name names or titles, I can confess that I've written coverage on some very celebrated and esteemed screenwriters. And those script notes were far less than any type of celebration or esteem.

One script, in particular, was written by a screenwriter with a rather inspiring story. They had beaten the odds and jumped from the bottom of the totem pole in Hollywood to the top with one of Hollywood's biggest stars committing to their script.

The story of this screenwriter — and I wish I could name who it was, but can't — is one of those undeniable anomalies in Hollywood. So with the success of their original screenplay getting purchased, produced, and distributed by some of Hollywood's biggest talents, I was thrilled to be the reader that read their follow-up.

I recognized the screenwriter's name as soon as I saw the cover of the script. Chills went down my spine because this was one of the first high profile writers I had covered.

And then I read the script. And then I instantly felt better about myself as a then-struggling screenwriter wondering if my work was good enough yet to be read by studios.

It was horrible. And this wasn't out of spite or jealousy. This script was horrible. Forget about the lousy structure, atrocious characterization, and on-the-nose dialogue throughout. The aesthetics of the script were a complete mess. Terrible format, spelling, and grammar — to the point that it was difficult to read.

The great thing about being a studio script reader is you get to learn what to do and what not to do as a screenwriter from both the best and the worst in the industry. No writer is immune to an outright disaster of a script.

I've since covered scripts from some of Hollywood's top talent. Most of them are excellent and a true testament to the fine craft of these staple Hollywood screenwriters. But sometimes those acclaimed writers would let you down.

Don't lose your opportunities because of on-the-nose dialogue. Learn how to write great movie dialogue with this free guide.

Confession #2 — "Most script readers start with little to no experience in film or screenwriting."

No, these are not film scholars reviewing your scripts. A majority are interns in their late teens or early twenties. The level above them are low-level assistants also tasked with answering phones, getting coffee, and ordering lunch for the executives.

I confess, when I first interned for an iconic director, I had no clue how to write script coverage. If I'm being perfectly honest, I had only read a handful of screenplays up to that point.

But before you get mad, understand that it's not about getting a scholar to declare that your screenplay is worthy of consideration — it's about entertaining someone with your cinematic story. It's about engaging them to the point where they can't put the script down until they reach the final page with anticipation. It's about moving someone enough for them to put their reputation on the line by typing RECOMMEND on that script coverage cover page.

Script readers get seasoned in screenwriting very quickly. When you read so many scripts in a short amount of time, you begin to see what works and what doesn't. That's why it's the best education a screenwriter can receive.

I've never taken a film course beyond a single screenwriting course that lasted for a few weeks. I have no film degree. During my days as a script reader, I had no optioned or produced screenplay. In fact, I had only written two or three horrible ones.

But man do I love movies. And that's all the experience a reader needs at first. Screenwriters don't need scholars to review their work and deem it worthy. You need to touch someone. You need to create a cathartic experience. You need to entertain them. You need to make them laugh as they've never laughed before, cry as they've never cried before, scream in horror as they've never screamed before, cheer as they've never cheered before, or turn the page in utter anticipation as they never have before.

Confession #3 — "Being a script reader is no fantasy position."

Before I became a studio script reader, I looked upon it as my fantasy career prospect.

"I get to read scripts for a living and give my opinion? Sign me up!"

That's all you do as a script reader. You get a bunch of scripts. You read them whenever and wherever you want. And then you get to write script notes that showcase what you loved about it, what you hated about it, and how the script could be written better. Sounds great, right?

It's bittersweet — and after time, more bitter than it is sweet.

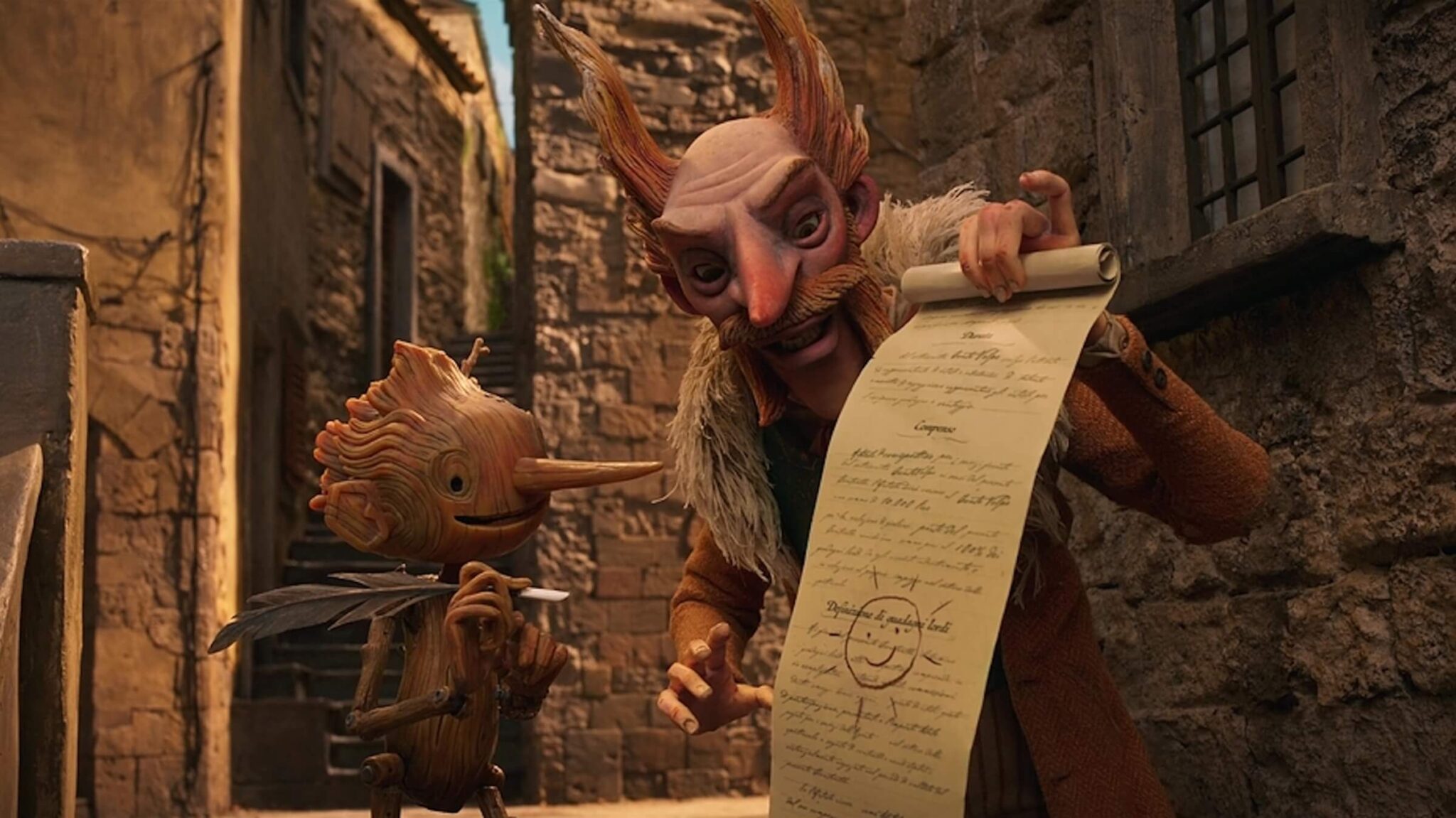

Yes, if you love cinematic stories, it's incredible to read scripts for a living. But the sad fact is that a majority of them are either horrible or horribly bland. It's not like you're reading Taxi Driver or The Sixth Sense every time. You're mostly reading knock-offs of current trends or a screenwriter's version of iconic movies.

And then imagine having to write a one to two-page synopsis of a story you hated and then write notes on why you hated it.

And even when a script isn't that bad, it's still not something you can stamp as a RECOMMEND, so you have to waste more time writing a synopsis and collection of notes for a script you know won't be read by your bosses (they only read the STRONG CONSIDER and RECOMMEND scripts — if that).

It would be different if it were just one script a week. But most script readers go through at least five to ten per week, if not more. Your eyes get tired from reading. Your hands get tired from typing coverage. Your mind gets tired from the monotony of reading lackluster script after lackluster script.

It's not fun. It used to be a treat reading a script but now since it's your job, it's become a chore. You're no longer trying to make Hollywood a better place by finding better scripts. You're just trying to get your way through the weekly pile so you can maybe find the energy to work on your own scripts at home.

Make no mistake, I highly recommend the job to any aspiring screenwriter. It's the best education you'll ever receive. But it's a grind.

Confession #4 — "I didn't read your logline, your short synopsis, or your passionate email query."

I get a call or email from my boss letting me know that there is a stack of scripts that need coverage. I go into the studio office, chat with the assistant, nervously chat with my boss about this or that script I covered the week prior, and then I grab the scripts and go (I'm dating myself, yes. Back in the early 2000s we still primarily read printed scripts. And yes, I saved my coverage on a floppy disk.).

That logline you spent so much time on? Didn't read it. That short synopsis you labored over? Didn't read it. That passionate email you poured your heart into? Didn't read it.

Read ScreenCraft's Writing the Perfect Query Letter for Your Scripts!

The good news is that somebody did because the script somehow got to me. It was likely the assistant or junior executive that vetted your query. But when I open your script, I know next to nothing about what I'm going to read.

Too many screenwriters use query emails to set the concept, story, world, and characters of their scripts up and fail to deliver on those elements within the first few pages of the script.

As I confessed in Part I, yes, I can tell if a script is going to be bad within ten pages. I’m not trying to be mean. I’m not trying to be arrogant or hold myself above others. I’m not lazy. It’s just a skill that every script reader picks up along the way.

But know this — I also can often tell if a script is going to be great within ten pages. That’s a skill that I’ve picked up along the way as well. Slow burn is not what you want to read in a spec script. It’s just a simple fact — the rules of the game. It’s not about giving us action or big shocking hooks. It’s just about engaging us. Give us a reason to read on. Find a way to pose a question and leave us hanging to the point where we need to read on. It’s not rocket science — it’s being a good writer.

You need to sell the reader in the opening few pages — and these days, ten pages is pushing it.

Find a way to get the concept, story, world, and characters of your script into those first few pages. I haven't read your logline, short synopsis, or email content. It's not my job. My job is to rate and review the script I just opened up, read, and closed.

Confession #5 — "As a screenwriter myself, I may have stolen... er... "been inspired" by what you did well in your script."

A thousand butt cheeks just clenched reading that line of confession. But relax. Allow me to explain.

The most "newbie" worry from screenwriters is, "I don't want anyone to steal my story or idea."

Look, if you aren't going to send your script out to Hollywood because you're afraid that someone is going to steal your idea, you're never going to get your script read, optioned, or produced. Plain and simple.

Hollywood is paranoid. They don't want to be sued. They'd rather buy your script than steal it and get sued in the public's eyes for millions once it's become a hit.

That's why it's so difficult to get your scripts into the hands of Hollywood power players. They would rather get it from a direct referral because it's safer (and the scripts have been vetted by someone they trust).

Now, about that stealing comment I made.

Allow me to quote Oscar-winner Quentin Tarantino in saying, "I steal from everything. Great artists steal; they don’t do homages."

And it was Oscar-winner Aaron Sorkin who said, "Good writers borrow from other writers. Great writers steal from them outright."

They're not talking about stealing scripts and passing them off as their own. They're not even talking about stealing direct scenes, sequences, or characters. They're talking about the fact that we are all inspired by each other as storytellers. Always have been and always will be.

If I see a type of character that a script I'm covering didn't really focus on — and I like it for whatever reason — I may apply it to my own work.

If there's a cool moment, emotion, visual, or world that has intrigued me from a script read, I may use my own variation of it.

I, nor most legit insiders in Hollywood, would never outright steal your ideas. I have plenty of my own rolling around in my head. I may be inspired or intrigued by some elements of your script that may work within my own cinematic stories, but that's not stealing. And those singular or out-of-context character types or story components aren't yours to own.

We're all inspired by what has come before and what is currently all around us.

Example: I had developed a television series pitch about a team of time travelers that traveled to the past to research historical events, utilizing secret technology not made available to the public or government. The show would be a visually stunning history lesson with each episode. Years later, this show popped up into the mainstream.

Beat for beat, and character by character, this show was almost exactly as I had envisioned mine would be. It was eerie how similar it was. And it was pure coincidence.

I had only shown my pitch to a couple of development executives — none of whom were affiliated with the now cult classic (and sadly canceled) NBC series Timeless.

We all live in the same pop culture zeitgeist. We've all been inspired by the same stories.

Stop fearing that someone is going to steal your idea. First off, it's likely being done by dozens of others around the world. Second, do your part to make sure that you're dealing with legit industry professionals with real film and television credits. Lastly, it's about how well you deliver on your version that matters most.

But again. Unclench. I likely just applied the visual you had in your script of a character swimming in the water at night, only to be pulled down under violently by an unseen force. That did seem kind of familiar though now that I think about it.

Until my next confession — keep grinding, keep writing.

Read ScreenCraft's How to Become a Hollywood Script Reader!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!