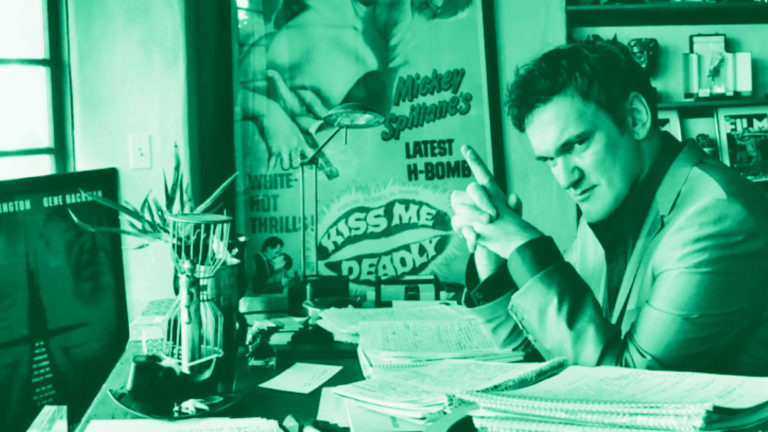

Screenplays vs. Novels: 7 Insights Quentin Tarantino Has Given on Writing Both

What is it like to make the transition between writing screenplays and writing novels? Let's ask Quentin Tarantino.

As we all know, Quentin Tarantino is one of the screenwriting masters of not just our generation but for all generations. But, he has always been a big fan of movie novelizations. As he pondered his (apparently) final film, he decided to dive into a novelization of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Deadline interviewed Quentin this summer, where the now-author discussed the idiosyncrasies of the differences between writing screenplays and novels. Here we share a few of his best quotes and elaborate on what screenwriters can learn from his observations.

Prose is a Fun Medium

"I like novelizations, and two years ago I started digging out my old ones. They were the first adult books I ever read, and I started re-reading the ones that I really liked and then reading some of the ones that I thought that I’d never got around to reading. I started thinking, 'What a fun genre this is. This is really cool.'"

Movie novelizations are an interesting hybrid. Sometimes they are written by the screenwriters of the movie. By guild standards, screenwriters are given that first option if the studio is considering movie novelizations.

Other times, authors are brought in to write the novelization — usually starting before the release of the film using the shooting screenplay. They are often given some freedom to expand upon the characters and storylines, including adding additional dialogue and background moments.

Screenwriters can utilize this kind of hybrid concept between film and literature by thinking outside of the box and considering the possibility of writing both a screenplay and a book.

The late Dances with Wolves author Michael Blake originally wrote the story as a screenplay in the early 1980s. He later worked with Kevin Costner on the 1983 film Stacy's Knights. Blake was reportedly staying over at Costner's house when Costner read the Dances with Wolves script. He and eventual Dances with Wolves producer Jim Wilson agreed that no studio would produce it despite its worth. They recommended that Blake write it as a novel and try to get it published — and then work to use a reader base to entice studios to adapt it for the screen.

Blake did just that. It was first published as a paperback and sold primarily in airports. It soon became a bestseller, allowing Kevin Costner himself the chance to obtain the rights knowing that the film adaptation would get the necessary studio distribution. The rest is Oscar-winning history.

We live in a multi-platform obsessed world. It's no longer about the single platform base. Movie studios require intellectual property for most of their productions — thus, they seek out novels to adapt. Publishers want novels that will also draw in movie studios for the adaptation rights.

This offers screenwriters a chance to play in both fields — for the benefit of their own projects.

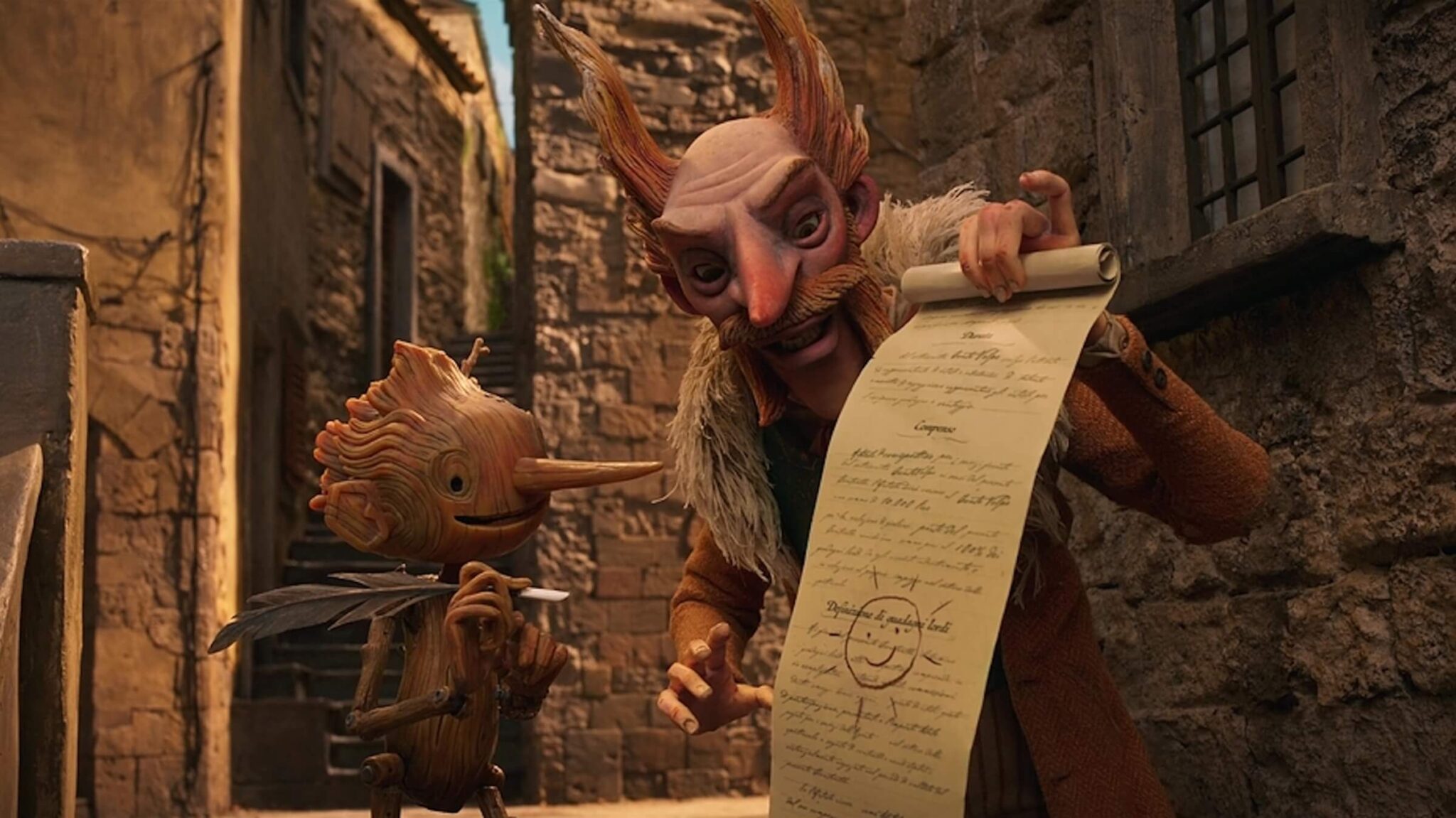

'Once Upon a Time in Hollywood'

Learn Who Your Characters Are Through Novelization

"I had all this material. I’m not talking about just a couple of scenes that got cut out of the theatrical release on the editing-room floor. During the five or six years I was writing the script, I kept writing out things that I knew would never be in the movie, just to make me learn about the characters. Sometimes I wrote in the guise of a cinema book, and sometimes when I needed to find out anything about Rick’s career, I just put him in another scene with Marvin and had Marvin ask him."

Writing a novel version of your screenplay offers you more freedom. And you don't always need to do it with the goal of trying to publish a novel. Sometimes writing in literary form can help you figure out your characters. That type of material isn't for industry contacts that you get the script to. Instead, it's to help you find your characters.

However, writing a novel with the intention of publishing it can give you opportunities to expand on your screenplay material.

- You can go into more detail.

- You can add more characters.

- You can explore backstory and tangent story arcs.

Learn What's Cinematic and What's Not

"In the third act of a movie, you’re not going to set a scene in a bar where these guys shoot the shit for 40 minutes. So it’s just not in the movie, but I wrote it out, and it was cool. I just have a lot of [material] like that."

Here we have an Oscar-winning screenwriter saying that not even he should slow the momentum of a third act in a screenplay with a talking head scene that slows the momentum down.

Screenwriters should take note. Many believe they can do such things because it's their grand vision of their story. Yet, they don't understand that screenplays are held to a different standard due to the cinematic limits of a two-hour (give or take) feature. The basic guidelines and expectations can't be ignored.

Even Quentin Tarantino understands this.

But that's what is intriguing about novelizing your screenplay. You don't need to worry about those limits.

'Once Upon a Time in Hollywood'

Prose Lets You Experiment with Your Ideas More

"I just thought it would be fun. And also it was a way for me to treat my book with the experimentation that I do with my films sometimes. Just the idea that you’re reading the book, and you get to Chapter 4, 5, or 6 or whatever, and then all of a sudden, there’s a Lancer chapter. And then it’s just the story, all right? It’s just the Lancer story told as if, all of a sudden, you’re reading a Western novel from 1966… and all of a sudden it feels like an Elmore Leonard Western or a Marvin H. Albert Western or a Max Brand Western, or Louis L’Amour. So you have that and then we go on with the ’69 story, and then there’s another Lancer chapter."

The concept of using the novelization of his screenplay/movie to extend his experimentation of cinematic storytelling that we've grown to love is compelling.

You always want to be experimenting with your craft. That's what is so dangerous about following screenplay formulas like beat sheets and such. It only leads to cookie-cutter screenplays. The scripts that get the most notice are those that push the boundaries.

You can do that with your screenwriting — and you can also accomplish that by turning your scripts into cinematic novels. The literary format is wide open. You can go off on tangents with chapters that explain the backgrounds of secondary characters, parallel themes, or minor story arcs.

Screenwriting Has Limits. Prose...Less So

"There’s a limiting aspect to a screenplay. It just can’t be whatever you want it to be. You are making a movie. And at some point, it has to [conform to] the length of a movie, at least for its initial theatrical run."

Once again, we have Quentin Tarantino understanding the limits of a screenplay. While his scripts go long because he's an auteur, he still recognizes the difference between having a story to tell and having a story to tell through the confines of a length of a movie.

Screenwriters need to accept that. There's a reason why your scripts should be between 90-115 pages. Movie length is often vital to the theatrical success of a film. Studios and distributors don't want two-and-a-half-hour movies (or more) unless they have the caveat of a big name like Tarantino or the attachment of a franchise.

Most films need that 90-120 minute movie to fit within the crowded theater viewing schedules.

But when you're writing a novel, you don't have to succumb to those confining elements of format and page length. You can do whatever you'd like.

'Once Upon a Time in Hollywood'

Working Outside of Your Comfort Zone is Hard At First

"The biggest challenge in writing? Screenplays are really easy for me. I’m not saying I don’t work hard — I work really hard, all right? But I know how to do it. Writing a novel, a piece of prose, was not hard, but it wasn’t easy. I’d never done it before. It was different than what I’d been doing before. I’d been writing these quasi-novels as my screenplays, but a quasi-novel is not the same thing as a novel."

Authors that attempt their first screenplay usually struggle with the confines, the structure, and the format. And they often struggle with not being able to use inner thoughts and unfilmable moments.

Screenwriters that attempt their first novel usually struggle with the prose. They are not used to needing to describe elements in more detail. But they do enjoy the freedom from the length and structure constraints. And the great thing about making the transition from script to novel is that cinematic books are a big draw for readers.

Authors with a screenwriting background tend to write books that read in a more visual and fast-paced manner, which many readers love.

No Page Counts Here...I'm Writing Prose

Quentin then details the comparisons between finishing his first feature script (True Romance) and his first novel (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood).

"You know, was it just going to be like all the other scripts I wrote, where I got up to Page 60 and stopped? So when I actually felt that I was going to finish True Romance, and it was going to be not 500 pages, that was exciting. That was really, really groovy. I was happy to get there. Well, I knew I was going to finish this novel. And if it was 400 pages, who cares?"

When you can finish a screenplay within the allotted confines in successful fashion, it's a huge accomplishment. Most screenwriters can identify with starting scripts and never being able to finish them when they first start their screenwriting journey.

Others struggle with keeping the page count down and understanding the general guidelines and expectations of screenplay structure and format.

When you write a novel, page count doesn't matter (within reason). Screenwriters are used to 90-115 pages (give or take). 400 pages don't represent a challenge for many screenwriters making that transition from screenplay to novel. The extended platform represents an opportunity to expand.

'True Romance'

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, and the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed starring Duane “Dog the Bounty Hunter” Chapman, Wesley Truman Daniel, Mickey O’Sullivan, John Victor Allen, and James Errico. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!