How do screenwriters know if they're overwriting their screenplays?

Overwriting is the first and most common hurdle that screenwriters need to overcome in their screenwriting.

Why Is Overwriting Bad?

Screenplays are a different type of writing platform compared to shorts stories and novels.

With short stories and novels, you're expected to focus on details and description. You're given the freedom to elaborate and expand on otherwise simple and straightforward visuals — primarily because with the literary platform, it's just the author and the reader.

Screenplays, on the other hand, are literary blueprints used for large scale collaboration to communicate the visuals of the screenplay through film and television mediums. It's not just author-to-reader — it's screenwriter to agent/manager, development executive/producer, director, talent, set designer, production designer, prop manager, wardrobe designer, special effects supervisor, stunt coordinator, cinematographer, and editor.

Because screenplays aren't published as literary manuscripts, it takes all of those people (and so many more) to get the content from screenwriter to audience. And each of those individuals — and their teams — bring their own stylistic collaboration to the mix in that respect.

So elaborate details and descriptions aren't necessary — or desired — for screenplays because screenplays are just the beginning of the collaborative cinematic process. Thus, scripts only require broad strokes. Broad strokes are all that is needed or desired.

What you want to accomplish in your screenplay is to create a cinematic experience within the read of your script. You want those visuals to fly off of the page, rather than meander in the details of description.

You want the read of the script to feel as if the movie is playing within the script reader's mind and imagination as fast as they are reading.

If you overwrite the script, you're not offering the script reader that experience, making it difficult for them to see the screenplay as a potential film. And, yes, overwritten screenplays are a hassle to read, which can affect a script reader's decision on which scripts to recommend and which scripts to pass on.

With that in mind, here are seven signs that you're overwriting your screenplays. Use this list as overwriting detectors, knowing that these elements are not required or desired.

1. Lack of White Space in Your Scene Description

Any good writer can write a whole page describing a room. You can be articulate by describing the sights, the sounds, the atmosphere, and then wax poetic about each and every one of those details.

There’s no room in a screenplay for that. If you delete those elements from your scene description, you’ll be well on your way to mastering compressed imagery writing.

You have to first think of it this way — each block of scene description is a visual you are trying to convey. And you need to convey it as quickly as possible for the reader to be able to see it through their mind’s eye. You accomplish with the less is more mantra we detailed above.

As you’re writing, you need to interpret each block of scene description as a visual that you are throwing at them:

This is what I want you to see.

Now you see this.

Now this happens.

There’s a beat to it. When you have long paragraphs of scene description, the reader’s brain registers it differently despite it saying the same thing. Even when we put those three short sentences into one block of description, the rhythm changes.

This is what I want you to see. Now you see this. Now this happens.

Same information, but when muddled together, it reads differently. But when white space is utilized to differentiate each image that you’re throwing at them — as is the case in the first example — you feel a rhythm that flows.

We can take it a step further in the direction of the musical context, beat-wise. That first example where those three lines are separated creates a rhythm.

Boom Bada.

Boom Bada.

Boom.

There’s a beat to it. But when you combine those beats by taking away that white space — that pause — you get a vastly different rhythmic experience.

Boombadaboombadaboom.

Do you see and feel the difference? Your mind just read that second example as more of a garbled sentence than a series of flowing beats. Your mind was forced to slow down, if not for a brief moment, to make sure that it was processing the letters correctly.

Keep in mind that these are simple fragments. When you apply this lesson to actual script pages and the scene descriptions within, you’ll quickly see how important white space really is. It creates that screenwriting rhythm that gives a script that “good read” feel to it.

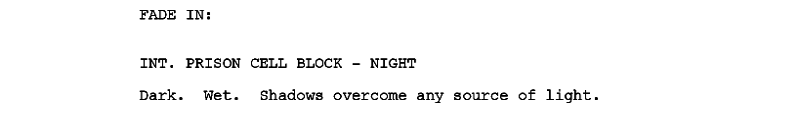

Here’s a clear example.

It’s actually not that bad. Two sentences for the first scene description paragraph, some white space, and then one longer sentence of scene description. But take a look at this next version of the same scene.

Short, sweet, to the point, and now you're ready to go onto the next.

If you find that your screenplays have big blocks of ink whenever there is scene description, you're overwriting your script.

Read ScreenCraft's How White Space Makes Your Screenplays Better!

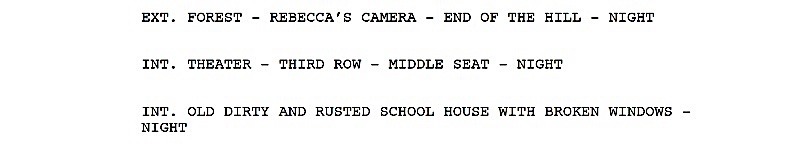

2. Overly Long Scene Headings

Another mistake many screenwriters make within scene headings is being overly specific.

Simplify, simplify, simplify. Save the details for the scene description.

Read ScreenCraft's Screenwriting Basics: The Keys to Writing Correct Scene Headings!

3. Multiple Camera Directions

Yes, you want to write a cinematic screenplay that offers the reader the experience of seeing the movie in their mind's eye as they read it, but that has nothing to do with including multiple camera directions and angles.

We don’t need to read every angle, every cut, every transition, every insert, and every sound effect.

We wouldn’t be mentioning this if it didn’t happen in a vast majority of screenplays from newcomers out there. It happens — a lot.

Don't waste screenplay real estate describing when and where the camera dollies, when and where we're at a close-up or long shot, etc.

It's the director and cinematographer's job to make those decisions. You're slowing the read down by asking the script reader to envision specifics. Remember, broad strokes.

If an angle, cut, transition, insert, or sound effect is pivotal to the story — rather than just the overall visual style — then utilize them every now and then. Beyond that, if your screenplay has a lot of camera directions, you're overwriting the script.

4. Overly Detailed Location Description

Now, this is different than the lack of white space mentioned above.

In short stories and novels, an author can go into specific detail about the setting and location of each moment within the story — it helps paint the picture for the reader.

In screenplays, that's not your job. We just need the broad strokes. That doesn't mean that you can't set the atmosphere. You just need to master the art of doing so quickly.

The above prison cell description comparison is a perfect example. While the longer and more detailed description of it has wonderful prose and offers more detail, the second example sells the atmosphere with just a few words in the body of some brief sentence fragments.

We don’t need to know every item in the background of a scene unless it’s pivotal to the plot. We don’t need to know the color scheme of the room. We don’t need to know the types of chairs, plates, appliances, and decorations.

We also don’t need to know what brand or type of car, computer, smartphone, or other items the character is using.

And we don’t need to know overly detailed descriptions of monsters, aliens, robots, or creatures. Let the professionals in those fields handle all of that for you as you offer the script reader the broad strokes, which then allows them to employ their own imagination to fill in the specifics.

5. Overly Detailed Wardrobe Description

Yes, actors will tell you that a character's wardrobe is a big part of the development of each character. However, within the screenplay, we only need to read a general description — if any.

The wardrobe comes into play when a costume designer gets their hands on the script. And then the director and actor come in to finetune the selection.

If you're introducing a character and going into specific detail about what they are wearing, you're overwriting that wardrobe description. A majority of the time, you don't need to go into any detail.

Only describe specific articles of clothing or wardrobe that are partial to the story and characterization. Everything else will either be assumed or detailed by the head of the wardrobe department and costume design.

6. Adverbs and Fancy Vocabulary

Stephen King wrote, “The adverb is not your friend. Consider the sentence ‘He closed the door firmly.’ It’s by no means a terrible sentence, but ask yourself if ‘firmly’ really has to be there. What about context? What about all the enlightening (not to say emotionally moving) prose which came before ‘He closed the door firmly’? Shouldn’t this tell us how he closed the door? And if the foregoing prose does tell us, then isn’t ‘firmly’ an extra word? Isn’t it redundant?”

Sure, adverbs do have a place in writing, but it's when you overuse them that the script becomes overwritten.

And that leads us to overly complicated or fancy vocabulary.

If you want to put together a pretty sentence, go write a novel.

Even then, it’s ill-advised to try to impress anyone with your vocabulary. Scripts are all about putting things into layman’s terms with the most basic words so that the script reader can process the description to see that movie through their mind’s eye as quickly as possible.

7. Blow-by-Blow, Gunshot-by-Gunshot, and Explosion-by-Explosion Action Breakdowns

Blow-by-blow, gunshot-by-gunshot, and explosion-by-explosion breakdowns get boring. And they take up a lot of screenplay real estate.

You will lose a reader quickly with that type of detailed description.

Action writing is about displaying the broad strokes for the reader. The important elements that shift the fight or chase sequences into the next gear.

Forget about the little exchanges of fists, feet, or bullets. It’s all about the major punch, kick, and gunshot that move the sequence forward.

If you watch a fight sequence like the iconic Bruce Lee versus Chuck Norris battle in Way of the Dragon, you’ll notice the major shifts in the fight.

Those opening blows wouldn’t be listed one-by-one within the screenplay. The script would simply read:

Violent and skilled kicks are exchanged until COLT (CHUCK NORRIS) CONNECTS HARD WITH A KICK TO TANG LUNG’S FACE, sending him flying to the ground.

That’s the first key moment to the fight.

The hero is taken down, surprised.

This is a major shift in the fight, thus it is the broad stroke that needs to be featured.

Then he takes more of a beating and goes down. Colt shakes his finger, which is another key moment that shifts the fight sequence — Tang Lung now changes his style and begins to dominate.

Any description you write within your action sequences should focus on broad strokes until it's time to feature big moments that shift the momentum.

Take a look at this iconic action sequence from The Matrix.

There is a lot of stuff going on, right? Lots of bullets, jumps, hits, reloads, and movement. Yet within the screenplay, the action sequence is just a quarter page of general scene description.

Less is more. Focus on the broad strokes and describing major moments, and then let the rest of the film's collaborators do their job.

Go through your screenplays and see if you can find any of these seven signs of overwriting — and then do a polish rewrite to eliminate them.

Learn how to master the art of the rewrite with this free guide.

For new scripts, read through this list before you start writing and make sure you don't fall into any of these overwriting traps.

Your scripts will be better and the people reading your scripts will be offered an amazing cinematic read — both of which will further increase your odds of success.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!