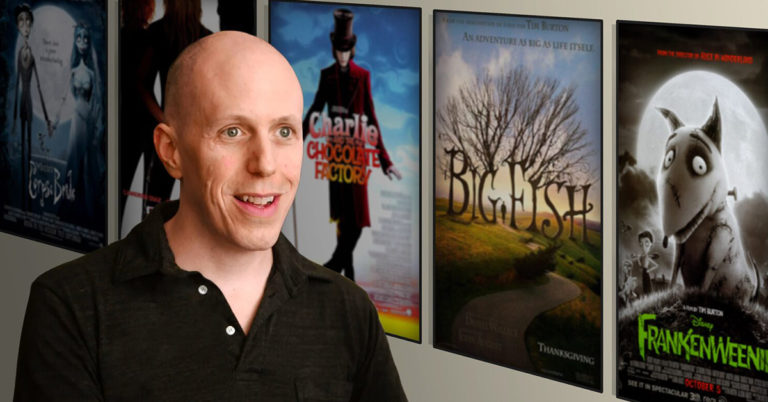

John August is a screenwriter known for his work on Go (1999), Big Fish (2003), Titan A.E. (2000), Charlie's Angels (2000), Charlie's Angels: Full Throttle (2003), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), Frankenweenie (2012), and the recently released live-action Aladdin (2019). He's also the author of a children's book called Arlo Finch. Based in Los Angeles, he co-hosts the Scriptnotes Podcast with Craig Mazin. He's been nominated for BAFTA and Grammy awards.

We recently had the chance to ask John a few questions about his process, the craft of screenwriting and what led him to develop the screenwriting software Highland.

ScreenCraft: You’ve written so many things in so many formats – from screenplays to songs to books to blogs to software to games to podcasts -- your creative output has been prolific and diverse. Tell us a bit about your daily habits that allow such prolific creativity. What’s an average day like in the life of John August? Are there any habits that you can credit to helping you cultivate such diverse and prolific writing and creativity?

John August: Monday through Friday, I’m up by 6:45 AM to get my daughter to school. I try to be at my desk writing by 9:00 AM every day. But try and succeed aren’t the same thing. I get pulled away a lot.

There are probably two to three hours a day where I’m at the keyboard writing. One thing that’s helped me most is sprints. Full credit to Jane Espenson on this. You announce on Twitter that you’re starting a #writesprint at the top of the hour. And then you just write for 60 minutes, no stopping. We even created a tool in Highland 2 called Sprint that allows you to set a timer in your document and tracks your word count for that run. I’d estimate that I wrote at least 70 percent of the second Arlo Finch in sprint mode.

When I’m really writing — that is, buckling down on a specific draft of a specific movie — I try to write five pages a day. Page counts tend to be a better measure of effort than time spent in front of the computer. For books, I try to get 1,000 words per day.

You know when you’re done. The brain just can’t make the words fit together. That’s a good time to go do something else.

SC: Of the various media you’ve written for, which kind of writing do you find most difficult and why?

JA: Books are harder to get through the first draft. Screenplays are harder to get through the overall process.

When you’re writing a screenplay you’re ultimately writing a plan for making a movie. So you are picking every word incredibly carefully, but ultimately you know that no one is going to see your plan necessarily in the finished product.

Screenplays end up being a very collaborative process. You’re working with executives and producers, actors, and especially a director, to figure out what that plan is going to be for that movie you hope to make.

Writing a book, the book is the book. It’s a remarkable experience because you’re working on the finished thing. I could really obsess about whether that comma should be there, and it mattered in a way that doesn’t matter in screenwriting.

As a novelist I have so many extra powers because I can describe the texture of sheets, I can describe how they smell, I can travel back and forth in time within the course of a paragraph. But because you have so many more choices, it’s a lot more work. Because a sentence can go anywhere in a book, you have to really work to figure out what you need to have happen next. It’s a very different experience building up a whole universe.

Coming to prose fiction after so many years writing screenplays, the hardest thing to get feeling natural was how we do dialogue in English prose. The “he saids” can get so clunky that you keep having to find ways around them, or let them disappear the way INT. and EXT. do. The second biggest challenge was learning how to write in the past tense without everything feeling “finished.”

To cover the same amount of story, you end up doing vastly more work in a book. But it’s rewarding in that you really are making The Thing and not a plan for making The Thing.

SC: Your undergraduate studies were journalism, and then you pursued an MFA in the Peter Stark Producing Program at USC. What did you learn about producing that informed your career and craft as a screenwriter? Is it important for emerging screenwriters to learn about the creative and business aspects of producing?

JA: I would say a career in screenwriting is like a career in journalism in that you are being paid to write for other people, and there’s a very specific form you have to follow, which can be great, but can also be frustrating at times. You’re boxed in.

The producing program ended up being a perfect degree for me, because it covered all aspects of making film and television, from physical production to marketing to story development. Most importantly, it let me understand what people who would be hiring me were really looking for.

SC: How do you think building a career as a professional screenwriter is different today than it was 20 years ago? What are some of the major changes you’ve seen in the industry over your career so far?

JA: For about a year, Steven Spielberg was attached to direct Big Fish, and I got to work on a few projects for him. I think the thing that was simultaneously depressing and exciting was realizing “Oh, he’s working really hard. It’s not like everything is easy for him.” When you see these extraordinarily talented folks are working really hard at being good at their thing, you realize, “Oh, I could work really hard, too.”

None of that has changed. If anything, the people I see succeeding are working much harder and much smarter than I did at the start of my career. They’ve grown up expecting that the world will shift dramatically, and quickly, so they’re not particularly interested in the last generation’s ideas of success.

Obviously, the last five years have seen a huge change with the rise of the streamers. We’re at a point of convergence where the distinction between film and television is largely erased. It’s probably the most exciting time of my career, but also the most uncertain.

Learn how to train yourself to be ready for screenwriting success with this free guide.

SC: How did you meet Craig Mazin, and what was the impetus to start Scriptnotes, your podcast about screenwriting?

JA: Craig and I each had blogs about screenwriting. He let his go after the writer’s strike, but I really missed his perspective on issues. So I emailed to ask if he’d be up for starting a podcast. That was 2011, and he hadn’t really heard of podcasts. But he was a natural for the medium.

Four hundred episodes in, we’re constantly finding new things to talk about. I think it keeps us both sharp.

SC: What led you to create Highland screenwriting software? How has it evolved?

JA: When we announced Highland in 2012, we billed it as a “screenplay utility” for converting between formats. I had a PDF of a screenplay that I needed to edit, and the only way to do it was to retype it. Which felt crazy. It was already a digital file. So I asked my genius coder friend Nima Yousefi if he could “melt” it down to editable text. He built an app that extracted the text, saving me hours of work.

But as I looked at that raw text, I realized that there was no reason I needed to mess with Final Draft again. That text had all the information we needed to build a proper screenplay. We started to embrace the fact that we were really a screenwriting app. We started to add tools that we’d been waiting for, like the Gender Analysis report.

With Highland 2, I wanted to extend the tools we’d built for screenplays for all kinds of writing. I’ve written all three Arlo Finch novels in it. I’m writing these answers in it. It’s pretty much the only thing I use for putting words together.

The most important factor why Highland works the way it does is that I use Highland every day for actual paid work. I rely on it, so major and minor annoyances get addressed. We’ve also grown a strong community of writers and we take their feedback seriously. Highland 2 is just a better way to write, because it was built by writers. It’s fast and flexible. You never have to tell it how to format something. It just intuits which elements are which.

I’m particularly proud of the user interface we’ve developed for Highland 2. It feels like a 2019 app, not something dragged up from the 90s. The new features in Highland 2.5, which releases June 12th at 9:00 PM PST, let you stay in the app even through revisions.

SC: Along with Scriptnotes, which is an incredible resource for emerging screenwriters, what are some other resources you’d recommend for up-and-coming screenwriters to learn more about the craft and business of screenwriting?

JA: My own site, johnaugust.com. I also run screenwriting.io for really basic questions and answers.

I’m a big fan of Sundance’s new co//ab community.

The best resource for any aspiring screenwriters is to simply read as many screenplays as you can. The wonder of the internet is that nearly everything is available as a PDF. I’d encourage people to check out the Weekend Read app to read these on their phones as well.

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook!

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!