10 Screenwriting Rules from the Writer of GROUNDHOG DAY

Danny Rubin, the screenwriter behind the iconic classic Groundhog Day, recently shared his ten screenwriting rules for screenwriters.

Early in his career, Rubin spent many years writing and performing within improvisational theater companies. He also made a living writing industrial films and teleplays for children's television. He eventually segued into writing screenplays, including the features Hear No Evil, S.F.W., and Groundhog Day, for which he received the 1993 British Academy Award for Screenwriting and the Critics' Circle Award for Screenwriter of the Year, as well as honors from the Writers Guild of America and the American Film Institute.

Rubin teaches screenwriting worldwide, and from 2008-2013 he was the first Briggs-Copeland Lecturer on Screenwriting at Harvard University.

In recent years, Rubin adapted his Groundhog Day script into Groundhog Day: The Musical, which opened to rave reviews at the Old Vic Theatre in London in 2016 and earned him and composer/lyricist Tim Minchin the Oliver Award for Best New Musical. The show opened on Broadway in April of 2017 garnering seven Tony nominations including Best Musical and Best Book to a Musical.

Rubin wrote an article on Daily Beast, detailing his "rules" for screenwriters while stating that the comfort of rules can offer novice screenwriter's the proper motivation they need to move forward.

Here we feature those ten rules and offer our own brief elaboration for each.

1. Writers Write and Rewrite

"If you are a writer, you are actually writing things down. And then we rewrite. Getting to the end of a 120-page feature film is huge, and I often print it out and spend the rest of the day just picking it up and feeling its heft. I did that! Yes, I did! But getting to the end is not the same as finishing. Most writing takes place after the initial basecoat is laid down."

Rubin mentions the notion that everybody has what they think are great ideas for movies. Having great ideas doesn't make you a writer. The implementation of those ideas is the craft.

The rewrite process is where the real writing occurs. Tough choices need to be made in your edits, accompanied by the necessary creative additions that you conjure to make the story a more cinematic experience.

Read ScreenCraft's 7 Ways to Master the Art of the Script Rewrite!

Learn how to master the art of the rewrite with this free guide.

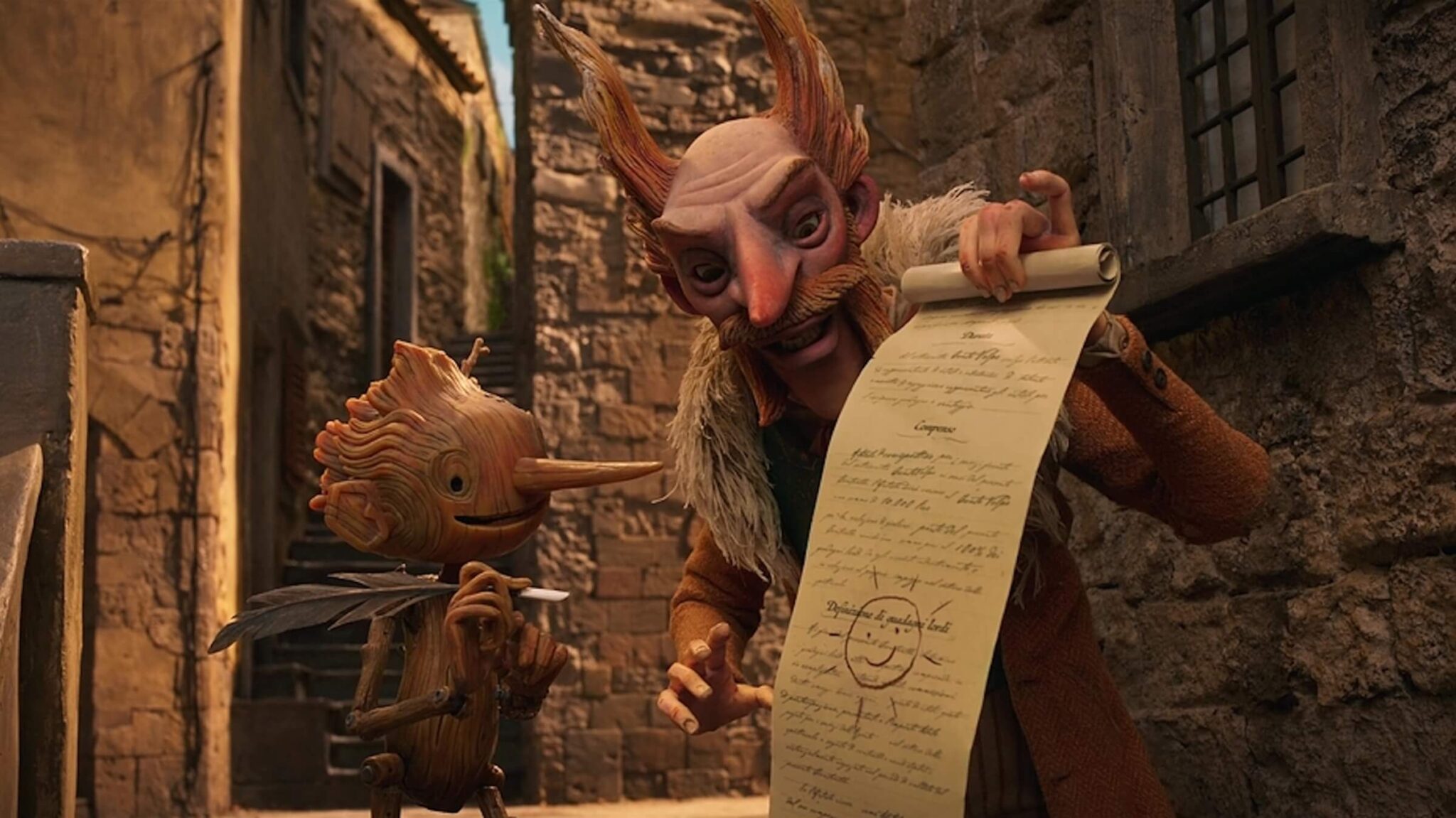

2. Show It, Don't Tell It

"Anybody can create a character who opens his mouth and tells us everything that’s on his mind, and some people can even make those words funny or poetic or heartbreaking. But movies are first and foremost a visual medium, and the strongest screenplays take advantage of that. What can a character do to show us how they feel or what they are thinking about? What scenes can you create and in what order can you arrange them in order to show us a routine or an intention or a memory?"

The most common issue with screenplays from novice writers is the reliance on dialogue to tell the story. Exposition is necessary for screenplays, but many screenwriters take it too far by having their characters deliver exposition dialogue dumps to explain away the plot and share inner emotions.

The secret to great dialogue is lack of dialogue. And you accomplish that by showing us rather than telling us.

Read ScreenCraft's How to Avoid Writing On-The-Nose Dialogue!

3. Write What You Know

"To write fantasies, or science fiction, for example, is to create worlds that nobody can know. Yet we often find our greatest truths in these kinds of explorations."

Every screenwriter has heard this piece of advice. So many misinterpret it as meaning that your best writing will be on subjects that you know about or experiences that you’ve experienced.

That is true, but there's more to it than that.

Writing what you know is all about applying your own experiences, perspectives, beliefs, and emotions into any necessary storyline. That's the creative part of genre screenwriting — finding elements that are real and cathartic amidst monsters, spaceships, robots, and other genre staples.

4. Economize, Less Is More, Small Is Large

"The best screenplays are not loaded down with redundancies, but instead are elegant structures characterized by efficiency and economy. Why give a speech when a nod will do? Every aspect of a screenplay is available for simplification, from the twists and turns in plot to the number of characters and scenes to the lines of dialogue. Good screenplays gain power from their simple efficiency."

Rubin goes on to point out that clever multiple agendas, plotlines, and parallel meanings can be intellectually satisfying for you or the audience, but they can also hinder the emotional impact of the story and characters.

The Less Is More Mantra is something that all screenwriters should embrace throughout the whole script.

Read ScreenCraft's Why Every Screenwriter Should Embrace “Less Is More”!

5. Know Your Structure

"Most screenwriting courses rest heavily on the teaching of structure. It is vitally important for a screenplay to have a clear, understandable, well-realized structure in order to stand, just as with a building or a bridge."

Structure is a highly debatable subject when it comes to screenwriting. There's no single structure that all screenplays must adhere to — there are many variances. But the story has to have some sort of foundation.

Read ScreenCraft's 10 Screenplay Structures That Screenwriters Can Use!

6. Raise the Stakes

"You don’t have to put a gun to a person’s head in order to make the stakes life and death. It can be a spiritual death. Getting a pimple on the morning of the prom can be life and death for a teenager. Whatever your stakes are, try raising them and see what happens."

The most common issue that most script readers have with the dozens of screenplays they read and reject every week is lack of stakes. If the character and story stakes in your screenplay aren’t up to par, it won’t advance up that ladder to be considered for contest wins, fellowships, options, representation, and acquisitions. So how do you go about raising the stakes in your script?

Conflict is inextricably linked with stakes. The more conflict you have in your script, the more stakes there are. And the more stakes there are, the more engaging the script story and characterizations will be.

Read ScreenCraft's Must-Read Analogy That Teaches “Raising the Stakes” in Screenplays!

7. Action Happens on the Screen

"As the screenwriter, you are the storyteller. Not the characters in your story. You. If you hear your characters begin to tell a story ('You won’t believe what happened in school today…' or I just had the most amazing day…' or 'I was just robbed!'), consider for a moment that the story they are telling might be more interesting to watch than watching somebody telling us that story."

This falls back to the show it, don't tell it directive. There's nothing more boring than having to read or listen to the dialogue of a character telling a story about what happened to them. We need to see it.

8. Make It Believable

"It doesn’t have to be true, but it does have to feel true. It has to be believable. Like a good lie."

Nothing can derail an otherwise great screenplay more than a moment that isn't believable. Once that occurs, all that has happened before — no matter how good it was — is meaningless because the reader or the audience will disengage. And they will do that because they've lost the trust they had in the writer.

It's the eye roll moment that too many screenplays fall victim to. That moment where the reader or audience rolls their eyes and shakes their head because what they just read or saw goes against what they know to be possible.

Even in genre stories, where reality is pushing the limits already, screenwriters need to set the rules of their story early and abide by those rules with a foot in relatable reality.

9. Eat Your Ego

"Remember that film is a collaborative medium. You will encounter many people with many agendas, and your job may be to incorporate ideas that are not your own, to make tonal shifts that do not feel like 'you,' or to make story choices that insult your intelligence. Can you do that? Always giving up your ego is called being a hack. Never giving up your ego is called being unemployed."

We've read plenty of screenwriting success stories filled with examples of ego. Both M. Night Shyamalan and Joe Eszterhas have written screenwriting books detailing many examples — either directly or indirectly — of their egotistical behavior. And too many screenwriters go into the industry not knowing the difference between confidence and ego.

You can be confident in your work and ready to defend it, while at the same time understanding that it's a collaborative medium and sacrifices must be made for the good of the film.

If you're driven by ego, you'll feel obligated to stick to your guns, refusing to compromise. And, yes, you'll find yourself being labeled as an undesirable personality.

10. Character Will Save Your Life

"When encountering a story issue that is keeping you from moving forward, the tendency is to look to plot for your solutions... or you could tinker with your character."

Every screenplay comes down to character. You could have the most conventional plot, but if you have that plot centered around a compelling character with multiple layers, the script is enhanced and the reader or audience will allow the otherwise familiar plot as long as they get to see that great character maneuver through it.

Don't turn to plotting to fix your story. Turn to the characterizations of your characters.

CLICK HERE to read the whole post with Rubin's extended elaborations and points!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!