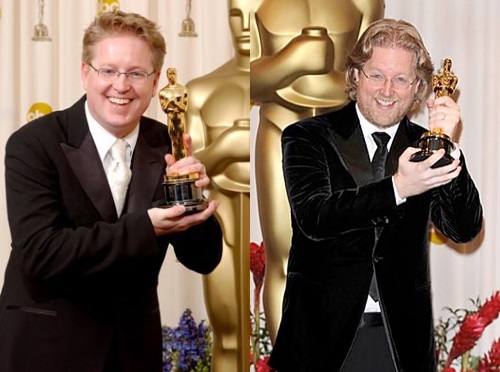

Pixar Director Andrew Stanton's Clues to a Great Story

What can screenwriters learn from Andrew Stanton — prolific Pixar writer and director behind Toy Story, A Bug's Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc, Finding Nemo, WALL-E, Toy Story 3, and Finding Dory — and his TED Talk where he offers his clues to a great story?

Stanton was raised in Rockport, Massachusetts and later attended The California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles, where he studied character animation. His first job after graduation was as a writer on the TV series Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures.

In 1990, Stanton was hired as the second animator and ninth employee of Pixar Animation Studios. He was one of the original driving forces of the animation empire that we know today and has been nominated for six Academy Awards, two of which he won (Best Animated Feature for Finding Nemo and Wall-E).

Stanton's TED talk features him speaking about what he knows about storytelling — starting at the end and working back to the beginning.

Stanton states that "[Storytelling] is joke telling. It's knowing your punchline. Your ending. Knowing that everything you're saying from the first sentence to the last is leading to a singular goal. And ideally, confirming some truth that deepens our understandings of who we are as human beings."

Here we feature his clues to a great story and offer our own elaboration.

1. Make Me Care

You need to make the audience care about your characters and the predicaments they're in. You accomplish this by injecting emotion and cathartic elements to the characters. When we feel that those characters are real, or better yet, when we feel a connection to those characters by relating to them, we care about what is going to happen to them.

And this works with villains and antagonists too. If you write these types of characters a certain way, whether we're intrigued by how bad they are and want them to get what they deserve, or we're relating to them somehow and want to see how the evil versions of us would react.

It's not enough to have a bunch of talking toys running around a room and then getting lost. If we don't care about those toys as characters, we don't care enough to keep reading.

2. Make a Promise

Early on in your script, you need to make a promise to the audience. You need to promise that the story you are about to tell is going to lead somewhere that will be worthwhile. Stanton states that there are many ways to do this and sometimes it's as simple as writing, "Once upon a time..."

He goes on to say, "A well-told promise is like a pebble being pulled back in a slingshot, [which] propels you forward through the story to the end."

3. Hide the Fact That You're Making the Audience Work

It's a misconception that audiences want the writer to carry them through the story. You must never underestimate the intelligence of the audience. Audiences want to figure out. The human race is a curious bunch. We're intrigued by a mystery. Our brains are natural problem solvers.

You don't need to overexplain the plot. You don't need to use dialogue to dictate what a character is feeling. Look no further than Stanton's WALL-E. The film's first hour or so is primarily silent — not a word of dialogue. But through the actions and reactions of our protagonist, we know exactly what he is thinking and feeling. We sense the wonder.

And that is because Stanton hid the fact that he was making us work as an audience. We weren't being spoonfed inner emotions. We weren't bombarded by bad expositional dialogue.

We just saw a guy meet a girl and fall in love.

If you decide to use dialogue to help tell your story, let us help. Learn how to write great movie dialogue with this free guide.

4. Unifying Theory of 2+2

And the way you make the audience put things together is by employing what Stanton calls the Unifying Theory of 2+2. You never give the audience 4. You always provide them with an equation to figure out. It's a simple one, mind you, but there's enough work within that equation for them to enjoy the process of discovery.

If you're writing a crime mystery, don't show the killer holding the smoking gun. Show their motive and then inject a later moment of discovery as the murder weapon is revealed in their apartment.

5. Find the Spine of Your Character

Stanton attended an acting seminar where the speaker shared her belief that all well-drawn characters have a spine, an inner motor, a dominant unconscious goal that they're struggling for, an itch that they can't fully scratch.

WALL-E's was to find beauty.

Marlin's was to prevent harm.

Woody's was to do what's best for Andy.

What are your character's inner motor, dominant unconscious goal, and itch they can't fully scratch?

6. Drama Is Anticipation Mingled with Uncertainty

This is the defining element of engaging storytelling. Have you, the screenwriter, built anticipation of what may happen to the characters? And once you've done that, have you mingled that anticipation with uncertainty? Have you thrown enough honest conflict at your characters to make us uncertain as to whether or not these characters will attain what you have been anticipating?

That's how you grab an audience. That's how you engage them.

7. Storytelling Has Guidelines, Not Hard Fast Rules

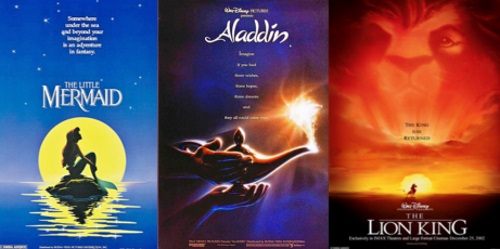

Back in 1993 when Pixar was developing its first feature animated film, Toy Story, they were struggling with the expectations of what animated features were at that time — The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, The Lion King.

While conceptualizing their approach, they came up with a list of what they didn't want to do.

- No Songs

- No "I Want" Moment

- No Happy Village

- No Love Story

- No Villain

Disney was freaking out. What they were developing didn't jive with what they thought were hard fast rules of feature animation. So they took the script to an unnamed Disney lyricist. Stanton states that the notes that came back from him assured that the film needed:

- Songs

- "I Want" Song

- Happy Village Song

- Love Story

- A Villain

In the end, Pixar had the last laugh as their vision for Toy Story went on to become an iconic classic, and paved the way for Pixar's "unorthodox" animated storytelling empire.

Yes, there are guidelines — and sometimes they apply. But there are no hard fast rules. Dare to be different.

Read ScreenCraft's The Differences Between Screenwriting Rules, Guidelines, and Expectations!

8. Find the Theme

Finding the underlying theme of your story that lays beneath the characterization and plotting is key. Stanton points to Lawrence of Arabia as one of his most influential films. And it introduced him to theme at a very early age.

The classic scene towards the end of the film where someone calls out to Lawrence, "Who are you?" That's the whole theme of the film. He's finding out who he really is.

What are the themes in your stories? When you know, and write with them in mind, you'll be connecting with the audience in a much deeper way.

9. Can You Invoke Wonder?

"Can you invoke wonder? Wonder is honest. It's completely innocent. It can't be artificially evoked. For me, there's no greater ability than the gift of giving another human being giving you that feeling. To hold them still for just a brief moment in their day. And have them surrender to wonder."

Stanton says that wonder is the true secret ingredient to great storytelling. Find the wonder in your concept, story, and characters and present those magical moments to them.

10. Use What You Know

To create real characters and cathartic moments of wonder, you need to use what you know in life. Your own life experiences and emotions can be injected into your story and characters to enhance the impact they have on the audience.

Stanton tells an amazing story, followed by an example of his own work where he employed his own life experiences. We'll let him do the talking.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!