3 Ways to Be Objective About Your Own Screenwriting

What is the pinnacle of a screenwriter's growth in screenwriting?

Being objective towards your own screenplays.

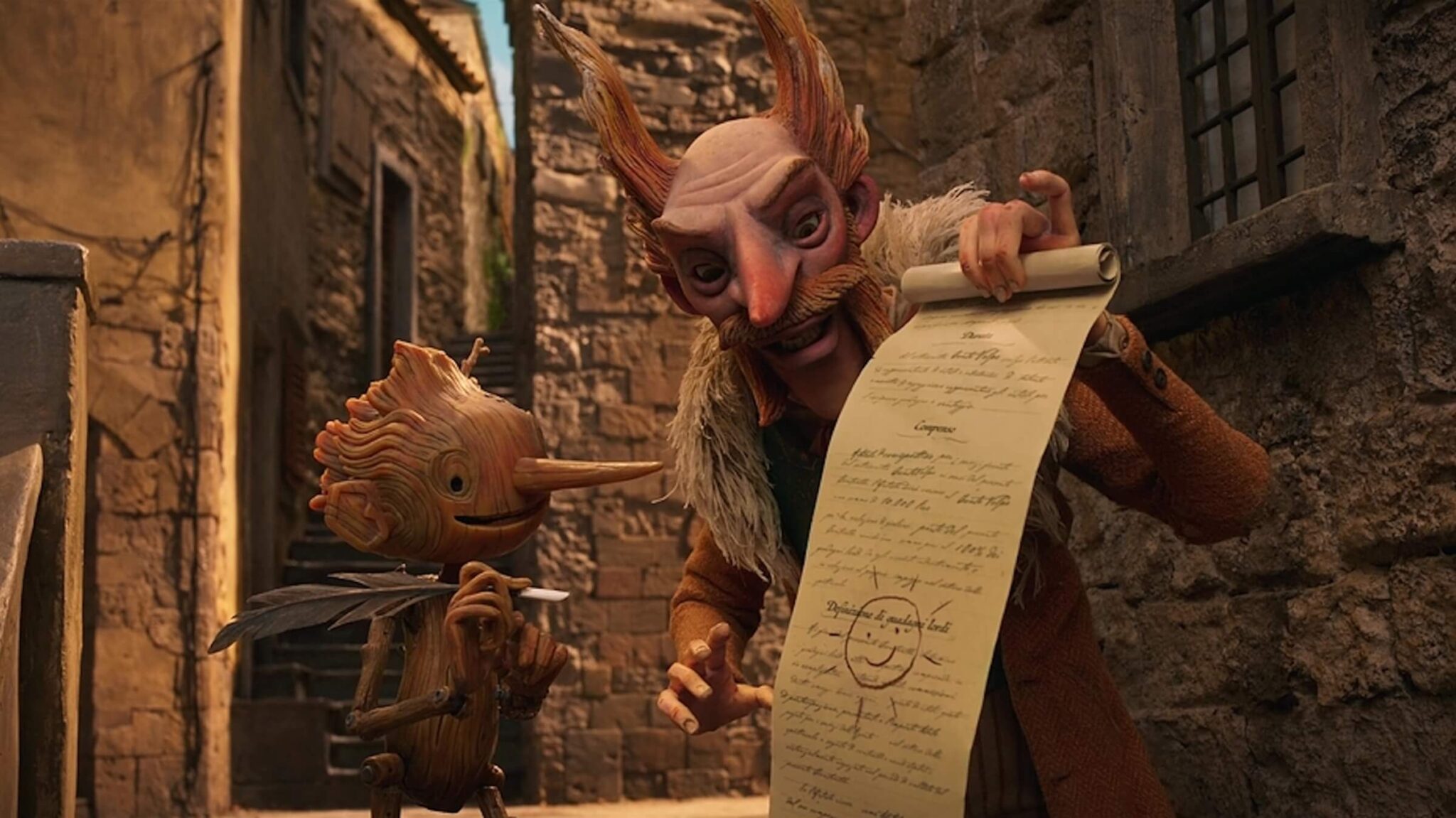

During the beginning of your screenwriting journey, you'll find that your worst enemy is often yourself. You start off by believing that your first screenplay is a surefire box office hit or easy Oscar contender. A majority of the time with most screenwriters, nothing could be further from the truth.

Then as you move on in your screenwriting career, you'll have much difficulty ingesting notes and feedback from managers, agents, producers, and development executives. While you try to protect your work's integrity, you'll slowly realize that it is a collaborative effort at that stage and the notes and feedback you get are often — but not always — based on objective wants and needs from your representation, producers, and the studios.

While your subjective feelings towards your own stories and characters will never disappear, you can take specific steps to learn to become more objective towards your work.

When you realize this eye-opening revelation, you will quickly see that your writing process, and your screenplays, will benefit.

Here are three ways how you can learn to become more objective towards your screenwriting.

1. Take a Long Break In Between Drafts

Physical vacations help people disengage from their busy and sometimes overwhelming work schedules. You get away from the stress of projects, deadlines, management, and hectic family life versus work/life schedules.

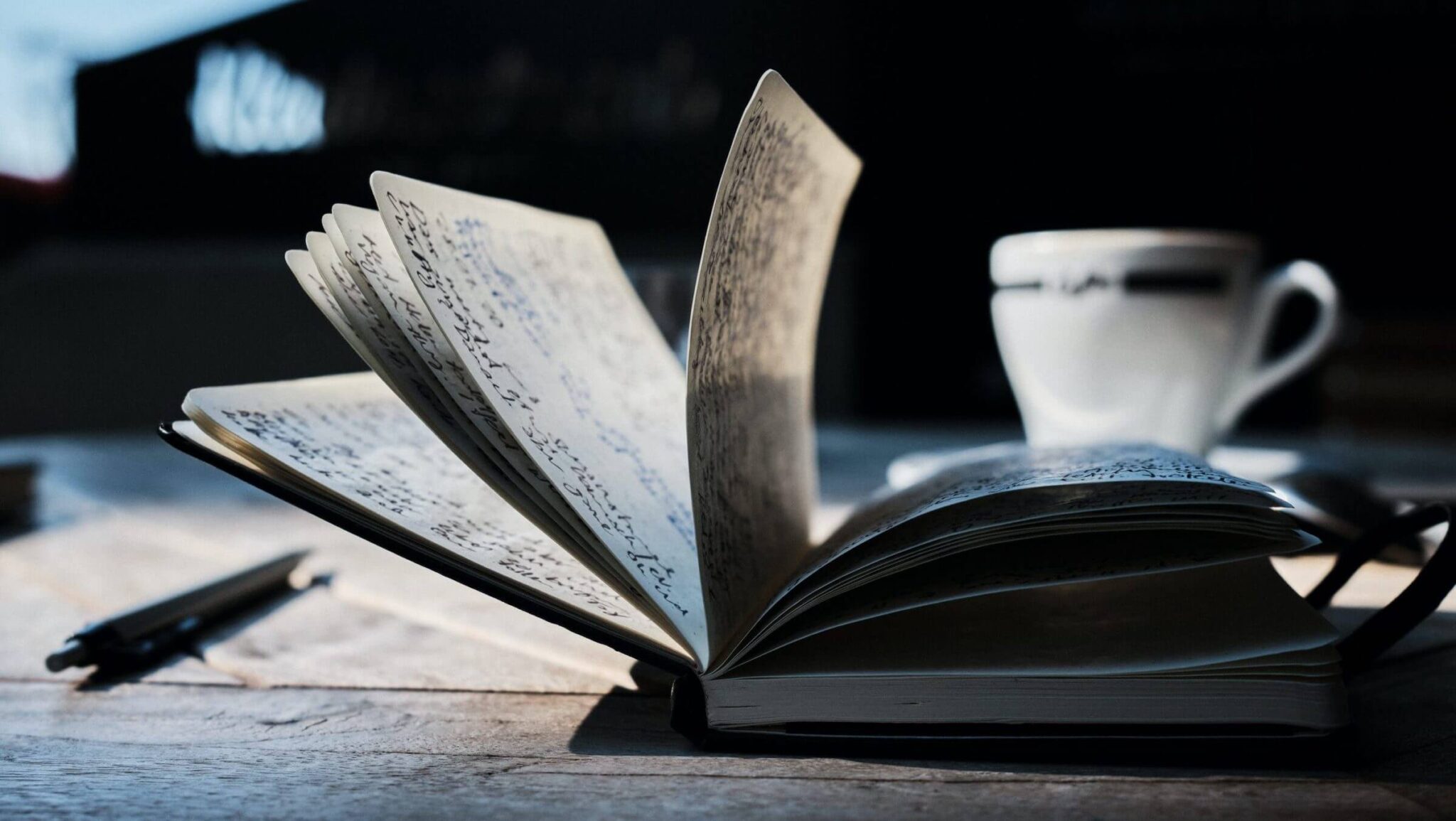

Mental vacations can accomplish the same type of relief as you take a mental break from your screenplay after finishing that first draft. You've just invested months of focusing on one particular script. You've forced yourself to become obsessed with every detail of the story and characters. And now you've finally reached the end. You've typed FADE OUT, FADE TO BLACK or THE END on that final page. You've hit SAVE. You've saved the draft to PDF.

There's a certain satisfaction to this end process. You feel the delight of completion. And now you're ready to take your "baby" out into the world. But before you do that, you have to work on that second draft. You have to shore up any and all plot holes. You have to make sure the script is up to par.

Before you get back to work, it's time for a vacation.

One day off between drafts isn't enough. One week off isn't much better. After months of obsessing over those details, you have to pull your mind away from the story, the characters, the structure, the pacing, and everything else. If you try to rewrite your script before you do that, you'll be on burn-out mode and feel as if every element you've written is the best it can be. They are not. At this point, you are too close to your writing, and your present mind is going to see what it wants to see.

Being objective is all about experiencing the script as a reader. You need to disengage from the details and problem-solving. You need to forget about your love for the story beats, the characterizations, and the choices you've made. You can't accomplish that with just a one day or one week break.

The best thing that you can do is take anywhere from two weeks to a month off. And during this time, you can't think about the script. You can't worry about the future marketing of it. You can't think about the characters, the story, or any other elements. You need that nice, long vacation where you detach from the workplace that is your screenplay.

When you return to it after upwards of a month, you then read the script cover-to-cover. Keep your red pen or laptop mouse aside. You're not at work here. You're the reader — the audience.

And when you read that script after that long vacation — as a reader, not the writer — you'll be surprised to find each and every story, character, structure, and format flaw, mistake or misstep that your subjective eyes one month prior would never have seen.

This is the first step in learning to become objective about your own screenwriting. And it's an important one.

It's best to master this process as early on as possible because years down the road when you've been hired to write a script, you won't have the benefit of taking a month-long break between drafts. You'll have to condense that to a few days to a week at best. So learn this first objective lesson now, so you're ready to write as a professional later on.

2. Become a Script Reader

While this coveted Hollywood job seems impossible to attain, you'd be surprised how easy it can be to work yourself into this educational position.

Writers groups online and locally near you can offer the necessary introduction into script reading as you read scripts from your peers and provide feedback. Coverfly offers a peer-to-peer program that will surely teach you the ways of a studio script reader and how they write studio coverage.

CLICK HERE to Visit Coverfly's Free Peer-to-Peer Script Exchange!

Once you have a solid set of script coverage samples, you can look up production companies, management companies, and agencies and then offer up your services as an intern or as a contracted script reader.

How does becoming a script reader help you be objective about your own screenwriting?

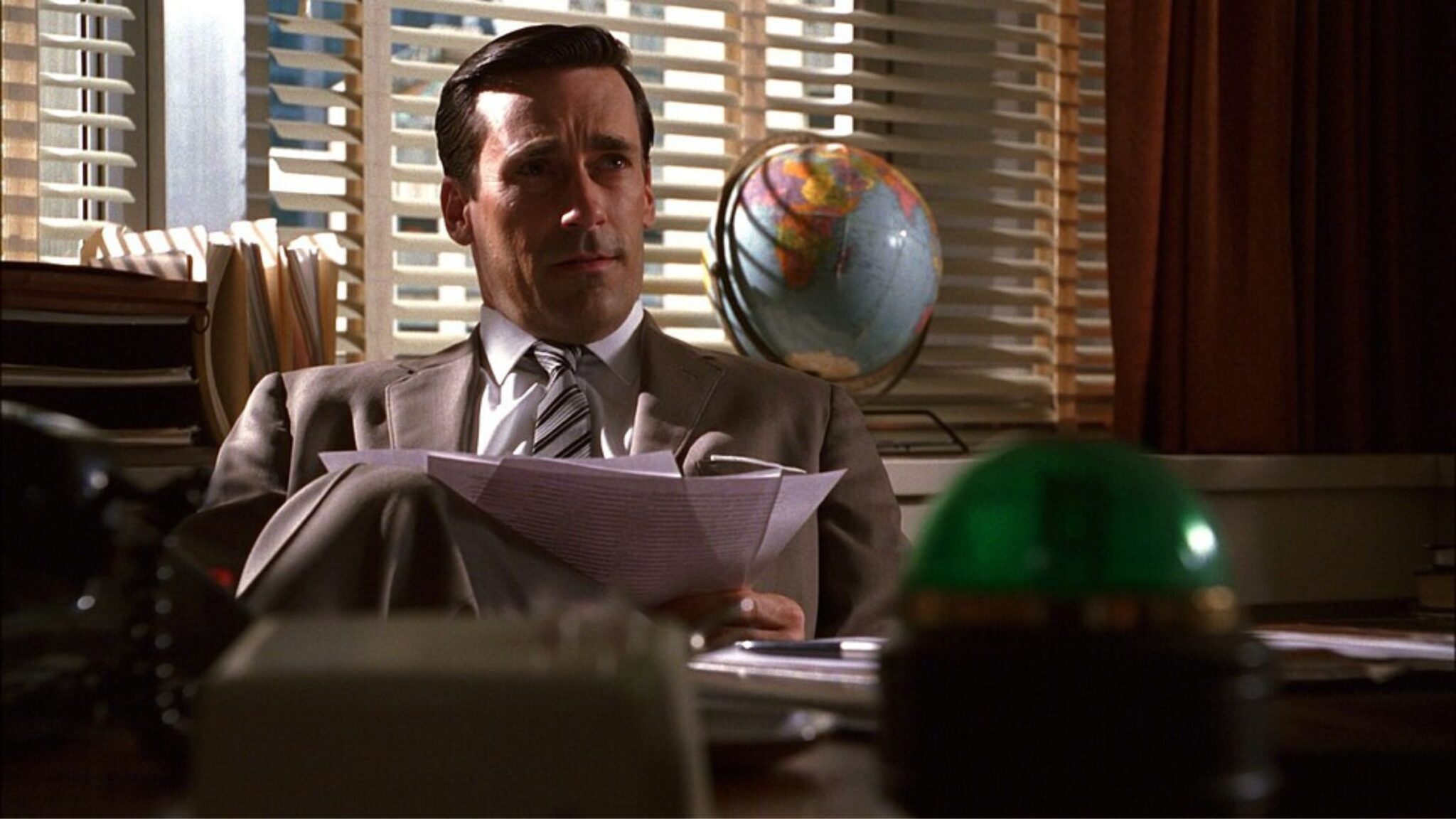

It's the best education a screenwriter will ever experience because you're reading multiple screenplays from both established screenwriters, as well as novice ones, which offers you a glance at the full spectrum of the screenplay market from the good to the bad and everything in between. You're also tasked with reading them through an analytical eye as you grade certain elements of the scripts and offer notes on those grades.

While there is undoubtedly a subjective viewpoint during this process, most professional script readers know that the companies they work for are looking for certain script elements. This forces the script reader to take a more objective approach to the read.

After you've covered a good number of scripts, you slowly begin to develop a keen eye for what works and what doesn't. You start to see where characters shine or fall flat, where stories engage or derail, and where scripts are strong and where they are weak.

Whether you're doing it for money, as an intern, or through peer-to-peer coverage services and writing groups, becoming a script reader and writing coverage teaches you to look at screenplays from a more objective point of view.

After you've taken that necessary break between your script drafts, you'll then be able to read the script as a reader even more so and spot the positives, the negatives, and everything in between.

Read ScreenCraft's How to Become a Hollywood Script Reader!

3. Put Your Script Through Terry Rossio's Script Reader Checklist

To write screenplays that engage and attract script readers and producers, you have to learn to think like them. You've hopefully accomplished that through some script reading on whatever levels you've explored (mentioned above), but a more detailed objective outlook is offered through Hollywood screenwriter Terry Rossio's Script Reader Checklist.

Rossio was also a script reader before he broke through and wrote hits like Aladdin, The Mask of Zorro, Shrek, and the Pirates of the Caribbean films. He created a specific checklist to help him in his evaluations, based primarily on the sometimes — but not always — arbitrary criteria that production companies, agencies, and management companies often impose on projects they are tasked with evaluating.

Applying this checklist to some of your scripts will help you get into the mindset of a script reader, producer, development executive, manager, and agent.

Checklist A: Concept & Plot

#1. Imagine the trailer. Is the concept marketable?

#2. Is the premise naturally intriguing — or just average, demanding perfect execution?

#3. Who is the target audience? Would your parents go see it?

#4. Does your story deal with the most important events in the lives of your characters?

#5. If you’re writing about a fantasy-come-true, turn it quickly into a nightmare-that-won’t-end.

#6. Does the screenplay create questions: Will he find out the truth? Did she do it? Will they fall in love? Has a strong ‘need to know’ hook been built into the story?

#7. Is the concept original?

#8. Is there a goal? Is there pacing? Does it build?

#9. Begin with a punch, end with a flurry.

#10. Is it funny, scary, or thrilling? All three?

#11. What does the story have that the audience can’t get from real life?

#12. What’s at stake? Life and death situations are the most dramatic. Does the concept create the potential for the characters lives to be changed?

#13. What are the obstacles? Is there a sufficient challenge for our heroes?

#14. What is the screenplay trying to say, and is it worth trying to say it?

#15. Does the story transport the audience?

#16. Is the screenplay predictable? There should be surprises and reversals within the major plot, and also within individual scenes.

#17. Once the parameters of the film’s reality are established, they must not be violated. Limitations call for interesting solutions.

#18. Is there a decisive, inevitable, set-up ending that is nonetheless unexpected? (This is not easy to do!)

#19. Is it believable? Realistic?

#20. Is there a strong emotion — heart — at the center of the story? Avoid mean-spirited storylines.

Checklist B: Technical Execution

#21. Is it properly formatted?

#22. Proper spelling and punctuation. Sentence fragments okay.

#23. Is there a discernible three-act structure?

#24. Are all scenes needed? No scenes off the spine, they will die on screen.

#25. Screenplay descriptions should direct the reader’s mind’s eye, not the director’s camera.

#26. Begin the screenplay as far into the story as possible.

#27. Begin a scene as late as possible, end it as early as possible. A screenplay is like a piece of string that you can cut up and tie together — the trick is to tell the entire story using as little string as possible.

#28. In other words: Use cuts.

#29. Visual, Aural, Verbal — in that order. The expression of someone who has just been shot is best; the sound of the bullet slamming into him is second best; the person saying, “I’ve been shot” is only third best.

#30. What is the hook, the inciting incident? You’ve got ten pages (or ten minutes) to grab an audience.

#31. Allude to the essential points two or even three times. Or hit the key point very hard. Don’t be obtuse.

#32. Repetition of locale. It helps to establish the atmosphere of film, and allows audience to ‘get comfortable.’ Saves money during production.

#33. Repetition and echoes can be used to tag secondary characters. Dangerous technique to use with leads.

#34. Not all scenes have to run five pages of dialogue and/or action. In a good screenplay, there are lots of two-inch scenes. Sequences build pace.

#35. Small details add reality. Has the subject matter been thoroughly researched?

#36. Every single line must either advance the plot, get a laugh, reveal a character trait, or do a combination of two — or in the best case, all three — at once.

#37. No false plot points; no backtracking. It’s dangerous to mislead an audience; they will feel cheated if important actions are taken based on information that has not been provided, or turns out to be false.

#38. Silent solution; tell your story with pictures.

#39. No more than 125 pages, no less than 110… or the first impression will be of a script that ‘needs to be cut’ or ‘needs to be fleshed out.’

#40. Don’t number the scenes of a selling script. MOREs and CONTINUEDs are optional.

Checklist C: Characters

#41. Are the parts castable? Does the film have roles that stars will want to play?

#42. Action and humor should emanate from the characters, and not just thrown in for the sake of a laugh. Comedy which violates the integrity of the characters or oversteps the reality-world of the film may get a laugh, but it will ultimately unravel the picture. Don’t break the fourth wall, no matter how tempting.

#43. Audiences want to see characters who care deeply about something — especially other characters.

#44. Is there one scene where the emotional conflict of the main character comes to a crisis point?

#45. A character’s entrance should be indicative of the character’s traits. First impression of a character is most important.

#46. Lead characters must be sympathetic — people we care about and want to root for.

#47. What are the characters wants and needs? What is the lead character’s dramatic need? Needs should be strong, definite — and clearly communicated to the audience.

#48. What does the audience want for the characters? It’s all right to be either for or against a particular character — the only unacceptable emotion is indifference.

#49. Concerning characters and action: a person is what he does, not necessarily what he says.

#50. On character faults: characters should be ‘this but also that;’ complex. Characters with doubts and faults are more believable, and more interesting. Heroes who have done wrong and villains with noble motives are better than characters who are straight black and white.

#51. Characters can be understood in terms of, ‘what is their greatest fear?’ Gittes, in Chinatown, was afraid of being played for the fool. In Splash the Tom Hanks character was afraid he could never fall in love. In Body Heat Racine was afraid he’d never make his big score.

#52. Character traits should be independent of the character’s role. A banker who fiddles with his gold watch is memorable, but cliche; a banker who breeds dogs is a somehow more acceptable detail.

#53. Character conflicts should be both internal and external. Characters should struggle with themselves, and with others.

#54. Character ‘points of view’ need to be distinctive within an individual screenplay. Characters should not all think the same. Each character needs to have a definite point of view in order to act, and not just react.

#55. Distinguish characters by their speech patterns: word choice, sentence patterns; revealed background, level of intelligence.

#56. ‘Character superior’ sequences (where the character acts on information the audience does not have) usually don’t work for very long — the audience gets lost. On the other hand, when the audience is in a ‘superior’ position — the audience knows something that the characters do not — it almost always works. (NOTE: This does not mean the audience should be able to predict the plot!)

#57. Run each character through as many emotions as possible — love, hate, laugh, cry, revenge.

#58. Characters must change. What is the character’s arc?

#59. The reality of the screenplay world is defined by what the reader knows of it, and the reader gains that knowledge from the characters. Unrealistic character actions imply an unrealistic world; fully-designed characters convey the sense of a realistic world.

#60. Is the lead involved with the story throughout? Does he control the outcome of the story?

Take a month-long vacation from your script in between drafts to distance yourself from the work. Read scripts and learn to write coverage to learn what works and what doesn't. Then learn to look at your script the way Hollywood insiders look at them.

Being objective about your own screenwriting is vital to becoming a successful screenwriter.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!