How do you know if a screenwriting contest, film festival, competition, or fellowship is legit, a scam, or something in between? This is a common question that we get from new writers.

With hundreds of contests out there, you'd be surprised to know that most of them are not the scams cynical screenwriters make them out to be — most of them are just wastes of time. A contest probably isn't a complete scam if its website lists answers to at least these 3 questions:

1. Who founded and/or runs the contest? If the website isn't clear about this, then writer beware!

2. Who are the judges for the contest? If the judges are listed, be sure to research their experience and projects they're credited. Google, IMDB and Wikipedia can be useful tools for this research. If no judges are listed, then writer beware!

3. Who has won the contest and has it helped their career? If you can't find any information on the contest website about past winners and how the competition has helped specific writers' careers (and verify those claims with a Google search of those writers), then there's a good chance that the contest is either too new to have a track record or else it's a scam.

These questions MUST be answered, otherwise you could be looking at a slick scam, no matter how prestigious the name of the contest or legitimate-looking the website. Don't be fooled if the name of the contest happens to have a famous city in its title like "Cannes" or "Beverly Hills" or "Chicago" -- these are lovely cities, but look closer at some contest's or festival's websites and you may find that it is very difficult to answer the three questions listed above.

We'll dive into the finer points of identifying which screenwriting competitions are worthwhile, but first...

Let's start with a brief history lesson of screenwriting contests for a little context.

A Brief History of Screenwriting Contests

If we want to really take it back in time, writing competitions actually go back thousands of years — before 600 BCE to be exact. Playwrights used to compete at the annual Greek Dionysia Festival, leading to winners being remembered and celebrated for millennia.

The art, craft, and business of screenwriting can be traced back to the 1890s during the advent of motion picture technology. In those days, screenplays weren't called screenplays — they were called scenarios. Back then, films were usually only a couple of minutes long. The scenarios written for those films by writers and filmmakers were basically brief explanations of, yes, the scenarios of the films.

As films evolved into more complex narratives, many such scenarios were written for one single film. George Melies’s iconic A Trip to the Moon (1902) had a more contemporary scenario structure that resembled today's screenplay, with over thirty lines of basic description, locations, and dialogue.

https://youtu.be/_FrdVdKlxUk

As these cinematic narratives grew, a film industry was born. By 1910, there were ten thousand movie theaters just in the United States alone. The new movie studios that were making films were flooded with submissions. By 1913, Moving Picture World estimated that over twenty thousand scenarios had been submitted.

To engage fans and audiences, the studios held contests to discover new talent, complete with cash prizes. This was the birth of what we now refer to as screenwriting competitions.

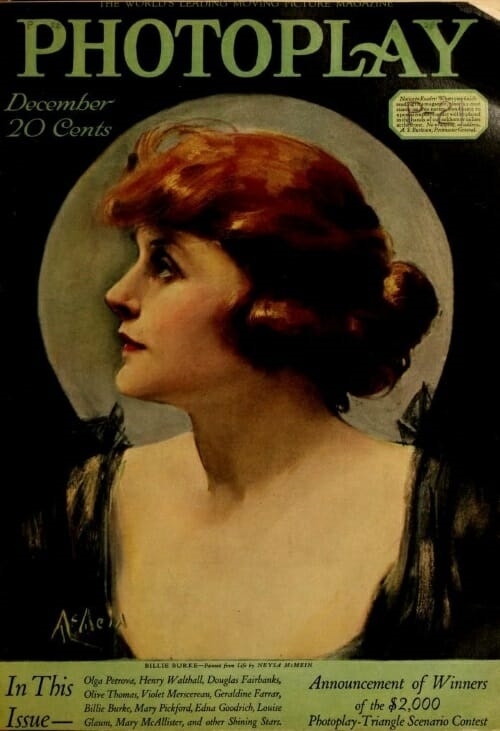

From 1915 through the 1920s, women were targeted as a key demographic for contests. Magazines like Photoplay courted women for careers in screenwriting as a direct alternative to acting, where many women were being treated horribly and taken advantage of. The magazine even hired Elaine Sterne, winner of Vitagraph Studio’s International Scenario Contest, to write a monthly column entitled Writing for the Movies as a Professional. Photoplay ran many scenario contests through those years, leading to big cash prizes for female writers.

When the magazine switched its focus to the glitz and glamour of Hollywood by the end of that decade, her screenwriting articles stopped, as did the contests.

While the Great Depression shattered the lives of millions, many turned to cinemas for some much-needed escapism. Musicals were the top draw, making stars out of talents like Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, Shirley Temple, and Fred Astaire as they represented strength, courage, optimism, charisma, vulnerability, and triumph. Qualities that the country — and the world — longed for.

Because of this musical genre obsession, scenarios and screenplays gave way to musical composition during this period of time. The contest market dried up for two decades until 1955 when legendary movie pioneer Samuel Goldwyn Sr. created the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards at UCLA to encourage young stage, film, and television writers. It wasn't an open competition mind you, as you had to be an undergraduate or graduate student to take part, but it reinvigorated the screenwriting contest.

A major shift in screenwriting contests occurred in 1979 when the AFI Alumni Association Writers Workshop was started by Willard Rodgers. The cash prize was no longer a major contest draw — it was the industry access that drove submissions with writers hoping to attain mentorship from Hollywood insiders, followed by live readings from a group of actors. Major films like Crossroads and River's Edge emerged from these workshop readings. The workshop was known as one of Hollywood's best-kept secrets.

However, costs to run the contest and eventual workshop each year were high — in large part due to the Xerox printing of scripts that was required for the judging process and eventual workshop treatment of the scripts.

In 1985, the esteemed Nicholl Fellowship was created by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. To this day, primarily due to its connections to the Oscars and the usage of tried and true Hollywood insiders as judges, this fellowship is considered the pinnacle contest of its kind.

And then the screenwriting boom of the 1990s happened. After the 1988 Writers Guild of America strike, there was a sudden surge of demand for screenplays and concepts. A plethora of screenplays were sold for millions — both by established screenwriters and newcomers as well. This enticed millions of people from around the world to try their hand at screenwriting.

The secondary industry of screenwriting was born. Screenwriting contests were all the rage. Screenwriting books were becoming bestsellers. Screenwriting gurus and consultants flourished. Everyone wanted a chance at the dream and everyone seemed to be more than willing to reap the benefits of those desires.

For two decades the screenwriting contest began to develop a bad rap because of that. There were the good, the bad, and everything in between.

MovieBytes creator Frederick Mensch commented on the impact that the internet made, “When MovieBytes went online in 1997, there were only about 35 or 40 contests worldwide, and most of them were pretty obscure. Almost immediately, though, we started getting 2 or 3 new submissions every week, and our database just took off. We were soon tracking hundreds of contests of all shapes and sizes.”

Once the internet was embraced, screenwriting contests grew in numbers — forcing screenwriters to wonder which contest was truly worth the time, effort, and money.

After the 2007/2008 double-punch of the Writers Guild of America strike and economy collapse, Hollywood was upended. The days of million dollar contracts for original screenplays were few and far between. Hollywood grew weary of anything that involved taking a risk, which is why intellectual property is still highly valued. And which is why Hollywood has been flooded with superhero movies.

But the scripts kept coming. More and more writers wanted in. By the second decade of the 21st century — primarily because of the influx of submissions and queries — managers, agents, development executives, and producers began to use screenwriting contests as filtration systems. And still do to this day.

"The cream will rise," is what they say.

But how do you know which contests, competitions, and fellowships are truly worth entering? How can you differentiate the bad from the good, and the many in between that are just dead ends?

The Difference Between Scams and Wastes of Time

By definition, scams are a dishonest scheme or a fraud.

With hundreds of contests out there, you'd be surprised to know that most of them are not the scams cynical screenwriters make them out to be — most of them are just wastes of time.

So many film festivals hold so many screenwriting contests. You pay your submission, submit your script, and maybe — if your script is good enough in the eyes of the readers and judges — you win some cash and get your name in the local paper or online. Maybe you even get your script read by local actors. While the vanity aspect of that win might make you feel good about yourself as a writer — appreciated — in the end, it's all a waste of time if your goal is to become a Hollywood screenwriter.

But it's not a scam.

You are given the option to submit. You know that only a select few can make it to the finals. You know that if selected you'll get X, Y, and Z.

Any and all contests are a risk because there are no promises that you'll win — no matter how good you think your script is. But just because there is a risk factor doesn't mean that you're being scammed.

If you submit your screenplay to a production company, studio executive, manager, or agent, there's no guarantee that they'll purchase and produce it, right? With contests, you're just paying for the opportunity to get your script through the door for whatever consideration they are promising.

Outright scams are difficult to prove and identify. You just need to gauge what contests, competitions, and fellowships offer you the most to help you attain that end goal of becoming a Hollywood screenwriter. And you have to make sure they have the proof to back up those claims.

The Proof Is in the Proving

Research is everything. When detectives are looking for proof that a suspect has committed a crime or fraud, they have to do the necessary research. They look into the backgrounds of the suspects. They question suspects and attempt to validate their stories, claims, and alibis.

You have to do the same thing when it comes to screenwriting contests, competitions, and fellowships.

Take the time to sit down and find out who they are, who is running them, how they are running them, what their background is, and investigate the claims that they make.

If a contest is backed by either reputable companies (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Final Draft, HBO) or individuals that have worked in the industry (research the companies they've worked for), it's usually a safe bet.

If a fellowship is under the wing of a major studio (HBO, Universal) or film festival (Sundance, Austin, Tribeca), it's usually a safe bet.

If there is no big industry name running the competition that you recognize from the get-go, now it's time to shift attention to the judges. What studio or production company do the judges work for? What are their film or television industry credits? If they are managers or agents, what management companies and agencies do they work for? If you research them and find little to no worthy film or television titles attached to them, the company they work for, or their clients (in the case of managers and agents), chances are you're wasting your time.

Again, you're not necessarily being scammed, but are those judges and promised contacts going to be able to give you the access you need to have a go at a viable screenwriting career?

If you look at websites for majors like Nicholl Fellowship, PAGE Awards, or ScreenCraft, you'll find specific updates on which winners and runners-up have signed with what companies. You'll be able to read bios of the people running the contests, competitions, and fellowships as well. You'll also likely be able to find reviews and comments on social media channels like Facebook and Twitter.

The proof is in the proving. If you're looking for some piece of mind to satisfy your inner-critic, just do a little research. If you feel the contest is a waste of your time, don't enter. If the contest website isn't transparent about contest administration or ownership, walk away. It's often as simple as that.

Beware the Pit of Poor Sports

Rejection is tough. The best of us have been rejected. The best above us have been rejected. It never stops. It never will. No matter how successful a screenwriter becomes. It's part of the business.

But when you begin to resent those that have rejected you, that's where you begin to slide into the pit of despair where poor sports linger and fade away.

Rejection should be used as a tool to better your work. The first thing you should do upon rejection is to investigate the possible reasons behind that rejection. Is the writing up to par? Is the format where it needs to be? Is there enough conflict? Are you relying too much on expositional dialogue?

After you've ascertained any and all issues on your part, you need to accept the fact that maybe it just wasn't for them — and then move on.

Screenplay Quality Is Primarily Subjective

Remember that not every contest will agree with the other when it comes to your script. No different than the fact that not every producer will agree with another about the same script.

The argument of "my script placed in the finals in X contest but didn't even place in Y contest, so Y is clearly a scam" is not a truth to live by. It's just the nature of cinema and art. Cinema and art are primarily subjective. And when they are objective, it's due in large part to either the script not being what they're looking for or, especially in the case of contests, the competition being tougher. Beyond those objective contexts, your script and its story and characters will be viewed with subjective eyes. There's no escaping that.

Most contests are just a waste of time in the long run. But that doesn't mean they are scams. A local film festival contest run by local writers and filmmakers with no film or television credits and offering little to no screenwriting career benefits is not a scam. But it may be a waste of your time, effort, and money.

Scams are difficult to identify — but contests, competitions, and fellowships that are a waste of your time are very easy to identify (within the context of your own wants and needs). Thus the simple guide to detecting screenwriting contest, competition, and fellowship scams is merely to stop expecting something to be a scam, and instead focus on deciphering if they are worth your time, effort, and money.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Tags

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!